Growth or stagflation?

Predictions for economic recovery belie enormous underlying risks. A sober look at the facts shows growth will be financed by massive debt, underpinned by increased money printing. A scenario for stagflation is increasingly in the cards.

In a nutshell

- Excessive money printing is fueling inflation

- Covid risks could hinder economic growth in rich countries

- 1970s-style stagflation could return, crippling economies

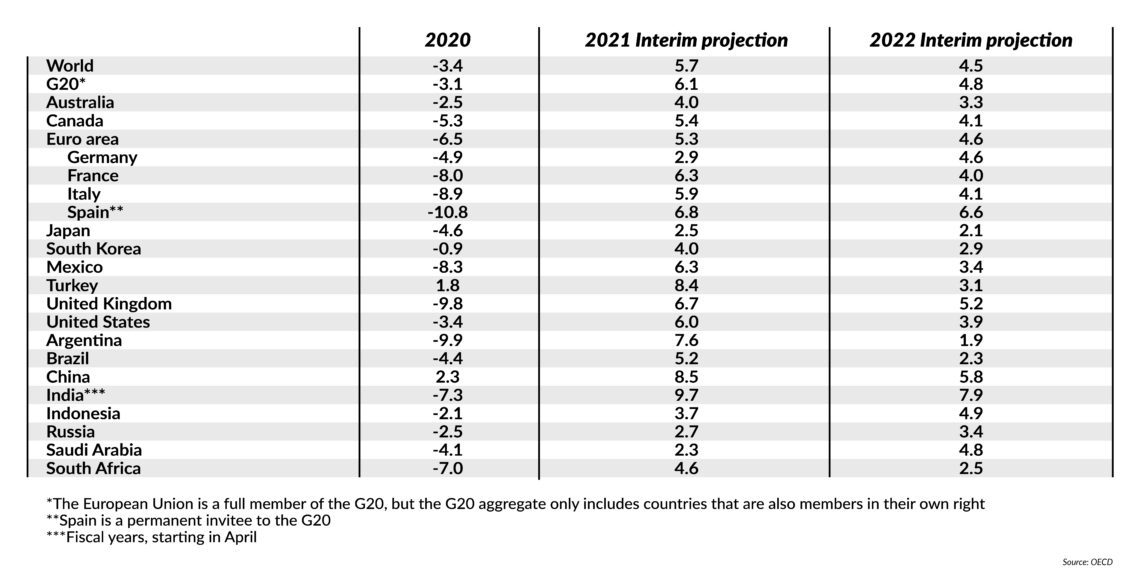

This autumn, major economic research institutions published their economic outlooks for 2021 and beyond. Forecasts for this year had to be revised down a little, but there is wide consensus that global gross domestic product (GDP) will surpass its pre-pandemic level this year and that the world economy will probably keep growing at a rate of between 4.5 percent and 4.9 percent in 2022. The numbers for most of the economically advanced G20 countries are even somewhat better than the global average (see table below).

It would therefore seem that the 2020 recession is fully in the rearview mirror and the recovery well on track. But the numbers should be taken with a grain of salt.

The contraction of global GDP in 2020 – by 3.1 percent according to the International Monetary Fund or 3.4 percent according to the OECD – seems surprisingly low. The official global Covid-19 death toll was nearly 2 million last year (2021 has already seen 3 million more). Moreover, according to the International Labour Organization the decline in hours worked in 2020 was equivalent to 255 million full-time jobs.

Facts & figures

Back on track?

OECD economic forecast (real GDP growth, annual % change)

The numbers for this year imply that the world economic recovery should be strong overall, but also unequal, even among the G20 countries. The euro area will not yet reach its pre-Covid GDP level by the end of this year, while the United States, South Korea and China will.

Nevertheless, major economic institutions’ figures show that almost all economies will return to solid growth next year and beyond. Whether that will happen, however, is highly uncertain. In its October outlook, the IMF acknowledges that the “balance of risks suggests that growth outcomes – over both the near and the medium term – are more likely to disappoint than to register positive surprises.”

The IMF mentions three major risks or uncertainties: “the evolution of the pandemic, the outlook for inflation, and the associated shifts in global financial conditions.” Each one of these could lead to a contagion that would bring the global economy to a state of slow growth or stagnation, possibly combined with persistent inflation.

Specter of stagflation

“Stagflation” – the combination of economic stagnation and inflation – was long regarded as a phenomenon of the past, an anomaly during the 1970s and early 1980s. Back then, the supply shock of rising oil prices triggered high costs and inflation. Trade unions pushed through high wage rises, leading to a wage-price spiral that central banks tried to stop with restrictive monetary policies, triggering a recession. Governments attempted to boost employment and growth with debt-financed spending programs that led to further interest rate hikes and the crowding-out of private investment. Slow growth, high inflation and excessive public debt reigned for more than a decade.

That was some 50 years ago. Of the two elements – stagnant growth and inflation – experts seem to think long-term high inflation is extremely unlikely, at least in the most advanced economies. Most economists, international organizations, governments and especially central banks are keen to portray the recent inflation rises (even to above 6 percent in the U.S.) as “transitory.” G20 consumer price inflation is expected to moderate from 4.5 percent this year to 3.5 percent by the end of 2022, and further decrease in the medium term.

What is missing is a sober look at the macroeconomic conditions.

One should expect such rhetoric from political institutions, since “anchoring” inflation expectations (avoiding a potentially self-fulfilling belief among the public that prices will rise) is part of their job description. These organizations rightly point out that some of the recent rise in inflation reflects base effects, following price declines for energy and commodities, as well as value-added tax and sales tax reductions in some countries in 2020. They also have reason to expect that supply shortages and bottlenecks in key sectors such as semiconductors, container shipping or aluminum supplies should gradually fade, and that energy prices and inventories will eventually return to average levels over the coming months.

What is missing from these optimistic accounts is a sober look at the macroeconomic conditions in most advanced economies. On the fiscal policy side, both the OECD and the IMF point to the enormous debt-financed public spending programs in the EU (Next GenerationEU) and the U.S. (American Rescue Plan) as “strong support” for future global economic growth. What they tend to minimize is the downside of using future taxpayers’ money to boost demand by pushing trillions of euros and dollars into areas where there are supply shortages.

In many G20 countries, the key sectors that these programs target, such as construction, information technology, health or (green) energy, face sizable bottlenecks in terms of basic materials and qualified labor. Even assuming that governments conduct all this public spending efficiently, when massive artificial demand meets significant supply shortages, higher prices follow.

Overall inflation is ultimately a monetary phenomenon. Supply and demand mismatches affect prices of specific sectors and commodities but may have little effect on economy-wide price levels as long as monetary growth is stable (that is, in line with production potential). But this is no longer the case.

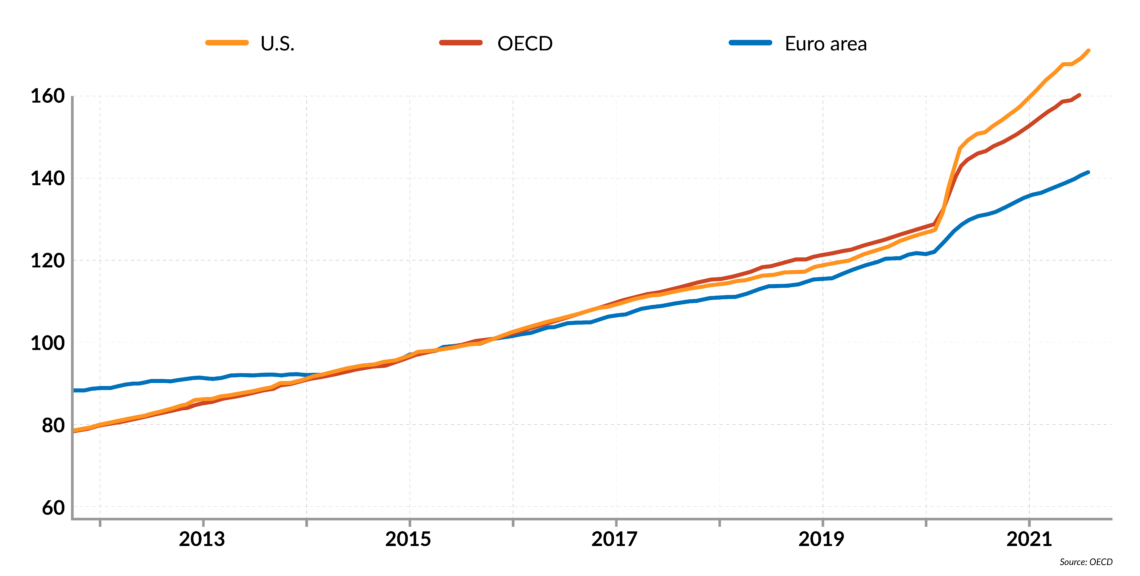

Facts & figures

Money-printing spree

M3 money supply

(Total. 2015=100, Oct 2011-Sep 2021)

The link between money supply and price levels is not trivial. However, if you only look at the usual consumer price indices and disregard prices of assets like real estate, there seems to be no clear connection. Until recently, money supply has outgrown real output without creating much visible (consumer) price inflation. Most of the additional money was used to finance government and bank loans, to inflate increasingly risky asset portfolios or simply to be kept in savings.

Since 2020, monetary policy has become extremely loose across the G20 and particularly in the U.S. All that money is likely going into the same channels as before, but now also to accommodate pressures on consumer and producer prices.

Eventually, this rapid growth will put pressure on central banks to slow down quantitative easing and raise interest rates. However, since most central banks have become accomplices or even hostages of highly indebted governments, it will be difficult for them to use monetary policy to fight inflation across the board. The specter of stagflation is no longer a far-fetched scenario.

Pandemic risks

Only a few G20 countries can claim to have (momentarily) tamped down the Covid-19 pandemic with the help of sufficient vaccination rates. Overall, some 60 percent of the population in advanced economies has been fully vaccinated, compared to about 40 percent in emerging markets and less than 10 percent in developing countries.

The heavily interconnected global economy is therefore still a long way from gaining immunity against the virus. Even advanced economies in Europe, Asia and the U.S. could experience renewed virus-related duress during the winter of 2021-2022. If the vaccines become less effective or new, deadlier variants emerge, we could be back to square one: supply-chain disruption, lockdowns, price pressure, corporate defaults and even escalating trade disputes or geopolitical tensions.

Under such a scenario, the stagflation dynamic could easily emerge. With a combination of (a) private supply bottlenecks meeting increased public spending, leading to (b) higher wage and price inflation, and (c) leaving central banks (especially the European Central Bank) in the awkward position of having to choose between reining in inflation or accommodating governments, banks and financial markets.

Germany’s role

Any medium-term outlook for the G20 or world economy will hinge on the U.S. and China. Serious uncertainties prevail in both of these economies. Vaccination rates are below expectations and local outbreaks of the virus (or possible variants) could not only endanger lives, but also weaken the world economy. China can lock down whole cities to contain the virus – as it has done recently in Lanzhou, a city of 4 million. The U.S., on the other hand, cannot apply the same measures. In each case, the risks to the delicate global supply chain are grave.

In Europe, similar risks of Covid variants persist but may be smaller due to higher vaccination rates. At the same time, however, the political risks to economic recovery are higher, making 1970s-style stagflation increasingly likely. The continent’s biggest economy, Germany, could lead the way.

Expect the new German government to pave the way toward European stagflation.

The elections Germany held in September still have not produced a new government. This is no surprise, since it will now take a three-party coalition to replace the former grand coalition between the center-right Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and center-left Social Democrats (SPD). What is more surprising is that the election winner, the SPD, will likely be able to form a new government before Christmas this year with the Greens and the liberal Free Democrats (FDP).

So far, few details have been revealed about the coalition talks. But it is reasonable to expect that the new German government will pave the way toward European stagflation.

The SPD seems to already have received agreement from the other two parties for raising the minimum wage to 12 euros per hour, one of its key election promises. To keep established workers’ pay proportionately higher, unions and businesses will want to increase overall wages (and thus production costs) significantly, especially where skilled labor is scarce. A wage-price spiral seems unavoidable.

The Greens have reportedly also secured agreement to one of their most important election promises, ending domestic coal consumption by 2030. With nuclear already phasing out in 2022, that raises the question: where will Germany’s energy come from, and at what cost? The country’s electric energy needs will increase as never before. For example, it will have to find a way to charge all the electric cars that, according to the Greens, should be the only ones allowed on the autobahn by the end of this decade. Germany already has some of the highest energy costs worldwide. A further climb up the energy-price spiral seems unavoidable.

It is unlikely that the ECB will tighten monetary policy to fight inflation.

The FDP, meanwhile, seems to have defended its red lines of no tax increases and no new public debt beyond what is allowed by the constitutional debt brake. It is the smallest of the three coalition partners but is insisting on receiving the finance ministry portfolio. If it does that, the party may be able to secure the constraints on spending, but fiscal conservatism is no guarantee for avoiding stagflation.

Even liberal finance ministers tend to prefer sustained levels of inflation. Inflation decreases the real value of outstanding debt and brings in higher tax revenues. In Germany’s system of exceptionally progressive tax rates, larger nominal incomes push citizens into higher tax brackets even if their real incomes have not increased. Hence, liberals can keep a promise not to increase tax rates while still increasing the real tax burden.

But whereas national governments and parliaments can control fiscal policy, they cannot control monetary policy. The European central bank has for decades helped national governments avoid difficult domestic reforms that would make their economies more competitive and fiscally sound. It is therefore unlikely that the ECB will tighten its monetary policy to fight inflation. After the recent resignation of Jens Weidmann – a well-known interest rate hawk – from the ECB’s governing council, there is no strong voice at the bank for a return to sound monetary and fiscal policies.

Scenarios

The global economic recovery may well be on track, even if most trains are running behind schedule. In the best-case scenario, the pandemic will fade, supply chains will fully reconnect or even improve, energy production will adapt to new economic and political demands, while digitization and other innovations will lead the way to new sustained growth. But the uncertainties for any outlook are enormous.

Even without significant pandemic-related setbacks, there are reasons to expect slower growth accompanied by higher inflation. In Germany, a mix of increased costs (wages, energy) could frustrate business and at the same time increase inflation expectations, accommodated by monetary policy. Similar, if not worse, scenarios could be found in other key economies. After 50 years, stagflation could return as a possible threat to important parts of the global economy.