Switzerland shows the many faces of inflation

While the prosperous nation of 9 million people has seemingly low inflation, monetary policy mistakes have eroded purchasing power and clouded its economic future.

In a nutshell

- Lax monetary policy failed to weaken the currency or prevent deflation

- Negative interest rates reduced the value of pension fund assets

- Best-case scenario: A short recession that corrects inflated prices

Switzerland has a reputation for responsible fiscal and monetary policies. The reported inflation rate of 3.4 percent in June 2022 seems to corroborate this image, especially when compared with 8.6 percent in the eurozone and 9.1 percent in the United States. The problem with this picture is: It is wrong.

The Swiss reality is, instead, marked by an ultra-lax monetary policy and a decrease in purchasing power since 2015. The Swiss situation serves as a case study for the many faces of inflation, a multifaceted phenomenon barely captured by inflation rates.

Inflation denotes an increase in the money supply not supported by an increase in the production of goods and services. Increasing money supply without real collateral just makes the bank’s balance sheets unjustifiably larger. This leads to a loss of purchasing power.

This loss, however, does not occur uniformly throughout the economy. Prices of some goods may increase faster than others, leading to a greater disparity in the relative prices of goods. Also, the increase of prices is just one manifestation of the loss of purchasing power, alongside skyrocketing valuations of real estate or exchange-traded securities and negative interest rates.

In other words, looking at the consumer price index as a proxy for inflation does not convey the entire picture. Inflation, the bloating of the money supply, shows itself in different ways in different sectors of the economy.

Switzerland’s bubble

In a bid to consciously weaken the Swiss franc, the Swiss Central Bank engaged in a prolonged phase of easy monetary policy. In January 2010, the Swiss Monetary Base Aggregate was about 87,000 million francs. By January 2020, it was around 589,000 million, peaking at approximately 757,000 in April 2022, with only a slight decline since then. In 12 years, the monetary base expanded 8.7 times.

This unprecedented bloat was initially championed on so-called technical grounds. The central bank, seen as committed to price stability, wanted to fight impending deflation. (One might ask, why? Deflation, the gain in purchasing power, can be economically viable. But this is a question for a different paper.) Increasingly, the bank’s true aims became clearer. Weakening the Swiss franc was a political move by a politically motivated central bank aiming at helping exporters through devaluation. Since the onset of this policy in 2010, its balance sheet expanded at unprecedented rates. As it proved unsustainable, the central bank decided to change its modus operandi by introducing a negative policy short-term interest rate. In the beginning of 2015, this rate went from 0.25 percent to -0.75 percent. Since then, it has stayed negative. Even after a very modest hike in June 2022, it still is -0.25 percent.

Facts & figures

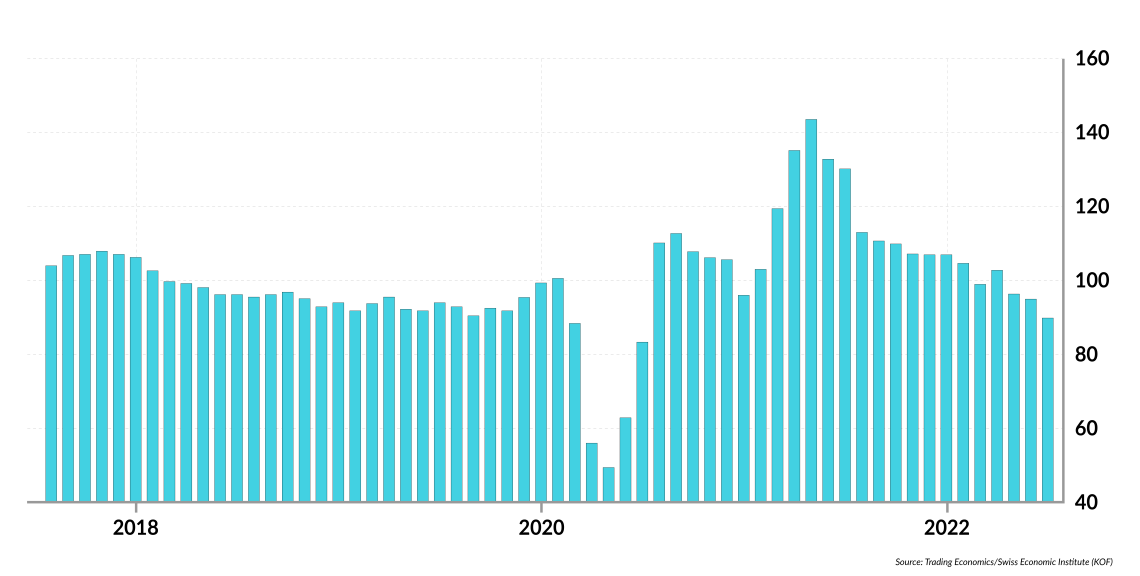

Swiss becoming less optimistic about the economy

Failed goals

Neither of the intended goals was realized. The Swiss franc appreciated against the euro, breaking parity in 2022, and since then becoming slightly more valuable than the European currency. The central bankers wanted to keep the Swiss currency at what they called the “fair” exchange rate of 1.20 franc per euro. Central bankers also failed regarding their other goal. Between 2010 and 2020, the yearly inflation rate measured by the consumer price index was six times negative – in other words, deflationary. In the other six years, it remained below 1 percent, and therefore below the policy band of 1-2 percent.

Housing prices climbed in real terms, making life less affordable.

Central bankers enlarging the currency supply neither maintained the Swiss franc in its “fair” exchange rate vis-a-vis the euro nor achieved their goal of fighting deflation. But this is only half the story of the Swiss failure. The other half is marked by the sectors in which a tremendous loss of purchasing power occurred – due to the machinations of the central bank.

Collateral damage

Alongside the inflation of the Swiss money supply, the country’s residential house price index went from about 130 points in 2010 to 190 in 2021. This represents an increase of over 46 percent or about 4 percent per year. This is much more than the development of wages, which are, on average, corrected by the consumer price index. The result is that housing prices climbed in real terms. With them, rents and other real estate-related prices made life less affordable, especially for the middle class.

Then, the Swiss Market Index went from around 6,500 points at the beginning of 2010 to about 12,900 at the end of 2021; even after all the turmoil of this year, it is still over 11,100 points. At its highest point, the market for exchange-traded shares almost doubled. It still trades about 70 percent higher than in 2010. In the same period, the Swiss economy grew by some 20 percent. Again, this difference is a sign that the increased monetary base did not enter the real economy, as was hoped for, but remained in financial markets, causing asset price inflation.

The reason for the seemingly low inflation rate in Switzerland is the failure of central bankers to devaluate the Swiss franc.

A third way in which the central bank’s inflationary policy diffused was via the pension system. One of the main reasons for the Swiss being relatively well-off is the mandatory but defined-contribution system of retirement provision. Currently, the whole system has around 1.3 trillion francs under management. The negative interest rate cut away some of these assets. First, the negative rates were applied to the pension scheme’s liquidity. Second, it lowered the bond market into negative territory as well as reduced the returns of the pension funds. Third, it led many funds to seek risks that were not appropriately remunerated by premiums. Negative interest rates chipped away at least 50 billion francs of the plan contributions.

Scenarios

The Swiss case shows how a bloated money supply leads to the loss of purchasing power. This loss cannot only be thought of in terms of the consumer price index because money diffuses differently in various sectors of the economy. In the Swiss case, the ultra-lax monetary policy led to an unprecedented high in the cost of real estate, to asset price inflation and to the deterioration of pension funds. On the other hand, this inflationary policy did not achieve either of its stated goals – devaluing the franc and preventing bouts of deflation.

How can this continue to develop? There are three main scenarios.

In the best case, Switzerland is hit by a hard but short recession that corrects the prices in real estate and financial markets, forcing the central bank to hike rates to around 2 percent and reduce its balance sheet. This is the best case also because it could stop the overheated Swiss labor market and could trigger an increase in economic productivity.

In the most likely case, the excessively loose monetary policy will turn into just a lax one. Rates will be adjusted to a low positive level, between 0.5 and 0.75 percent, and asset prices as well as real estate will continue to increase. Ironically, the strong Swiss franc absorbs some of the inflationary pressure coming from Europe and the U. S. In this case, Switzerland will continue its path of sluggish growth, an accelerated labor market and balance-sheet increases.

In the worst case – in addition to other maladjustments of the Swiss economy to the ultra-expansive monetary policy – inflation also makes itself noticeable in the consumer price index. This is likely to happen if the labor market accelerates even more and wage raises of around 2-5 percent are negotiated. In this case, the central bank will not be able to cope with price increases. Since the increase happens without a similar hike in productivity, this scenario is likely to lead to stagflation.

The case of Switzerland shows how multifaceted the loss of purchasing power of money is. It also showcases how dangerous it is to follow an excessively easy monetary policy, even if the consumer price index does not show inflationary tendencies. They are there but disguised in other forms.

The picture of responsible Swiss monetary policy is a mirage. It can only be maintained because of the nation’s low-key reputation and because its nefarious results pass undetected. The reason for the seemingly low inflation rate in Switzerland is the failure of central bankers to devaluate the Swiss franc.

Note also that the current drivers of inflation – in Switzerland and elsewhere – are all failures of policy: lax monetary policy, severe Covid-19 lockdowns and the rising supply and demand that followed, exploding energy prices due to political myopia and ideology, deglobalization because of protectionism and mercantilism, and war. The massive loss of purchasing power taking place now can be traced exclusively to too much central planning.