Swiss-EU trade talks: Sovereignty at stake

Switzerland’s government ended negotiations with the European Union on a comprehensive trade deal designed to update decades-old agreements. Doing so for Switzerland was a question of sovereignty – but it risks losing traction in the enormous, crucial EU market.

In a nutshell

- Bern saw the EU trade deal as infringing on its sovereignty

- More regulations could hurt its competitiveness

- The Swiss could find ways to make up for the lack of a deal

In 2019, Johannes Hahn was the European Union commissioner in charge of negotiating an institutional framework agreement (IFA) between the bloc and Switzerland. That year, he wrote to then-President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker, saying: “We simply cannot allow [Switzerland] further playing for time and watering down of single market rules, especially not in this presumably critical phase in connection with Brexit.”

The words showed little understanding of politics or partnership. Such agreements hinge on the two sides treating each other as equals. Someone negotiating in good faith and on equal footing would not use rhetoric about “allowing” the counterpart to do anything. But Commissioner Hahn was not only mistaken about the nature of negotiations. He probably also imagined that the EU would have an advantage over both the United Kingdom and Switzerland. At the time, this was self-deception; since then, he has been proven wrong. In Switzerland, too, plenty of people in politics and business succumbed to self-deception. The agreement was even described as “tailor-made.” Ingenious methods for stretching logic were found to justify it.

Politics and principle

But then in May 2021, the Swiss executive, the Federal Council, decided to end the negotiations. The draft agreement was buried along with it. The reason was not only political – that text would have never passed a popular vote – it was foremost one of principle. The IFA would have violated many institutions the Swiss consider central to their polity.

For example, Switzerland does not have the equivalent of a Constitutional or Supreme Court. The Swiss Constitution was adopted in the name of the cantons (the member states of the Swiss Confederation) and the people, and only the people can judge if a law is in accordance with it. The draft text of the IFA, however, gave the European Court of Justice the ability to pass judgment on Swiss laws and even overturn popular votes.

The IFA foresaw a stronger harmonization of the Swiss market, curtailing federalism.

Moreover, Switzerland has a market-oriented welfare system organized via insurance and coverage based on contributions. In contrast, most EU systems are state-sponsored with defined benefits. The draft text of the IFA foresaw the application of the EU Citizenship Directive to Switzerland, and with it, Switzerland’s obligation to extend benefits to Europeans, even without prior contributions. Switzerland is committed to its version of federalism. The latter entails the freedom of any canton to regulate its own economy, especially creating norms or organizations considerably different from those in other cantons. The draft text of the IFA foresaw a stronger harmonization of the Swiss market, thus curtailing federalism.

Finally, economic freedom gives each person the freedom to start, maintain and fail with a business at any time and without prior consent or license, with few exceptions. The IFA, however, would have imposed the EU’s idea of economic freedom, thus instituting the bloc’s byzantine mechanism of licensing and hampering entrepreneurship. There were also other elements in the draft text that were problematic in the Swiss political context. The questions regarding subsidies and the integrity of the labor market are examples of those. While Switzerland promotes a free economy, it or the cantons have many subsidies in place and the labor market is “protected” from immigration. These elements played an important role in ending the negotiations, but ultimately it was the question of sovereignty that closed the matter.

Sovereignty has a price

In Switzerland, the people and the cantons share sovereignty. This sovereignty has a price. Part of the price is that policymaking in the country is consensual; another is that this sovereignty must be defended. Switzerland ending the IFA negotiations with the EU is an example of the latter. Not only do the Swiss know that ending the talks came at a price, they were also willing to pay it.

Facts & figures

For now, Swiss-EU relations are based on the 1972 Free Trade Agreement, the 1989 Insurance Agreement, the seven bilateral agreements of 1999 (Bilateral Agreements I), and the 2004 agreements (Bilateral Agreements II). The idea of the IFA was to update and broaden all these treaties, putting them in the same framework. All these agreements remain in place. However, they are not up-to-date and have significant limitations. Also, as the EU continues to evolve – including introducing new regulations – parts of these agreements could erode, jeopardizing Swiss access to EU markets.

A look at the trade relationship between both brings this into perspective. The EU is Switzerland’s biggest trading partner, whereas Switzerland is the EU’s fourth largest after the United States, China, and the UK. Swiss merchandise exports to the EU are concentrated in a few sectors, particularly chemicals/pharmaceuticals and medical products, machinery, instruments and watches. On the other hand, Switzerland is an important partner of the EU for trade in services, in particular, for commercial services.

Each side knows that an erosion of the relationship between Switzerland and the EU would be detrimental to both.

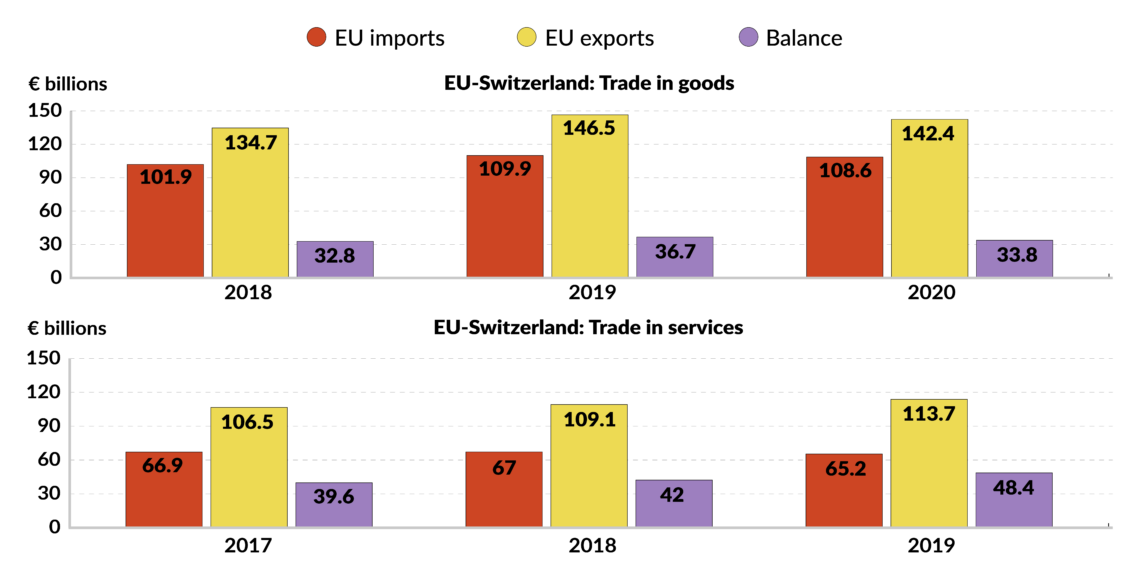

The EU is a net exporter to Switzerland. In 2020, the total trade in goods came to 251 billion euros, with a positive balance for the EU of 33.8 billion euros. In services, the trade volume equaled 178.9 billion euros with another positive balance for the EU of 48.4 billion euros (2019 data). These figures show how important the EU is for Switzerland and how high a price the Swiss are willing to pay for their sovereignty.

However, these figures also show how important Switzerland is for the EU. Since the EU is a net exporter to the Swiss Confederacy, it has no interest in losing this important customer. For some regions of the EU – for example, northern Italy or the German state of Baden-Wurttemberg, business with Switzerland outranks any other partnership. Additionally, Switzerland contributes around 1.5 billion euros to the transition of countries joining the EU. It is a welcome sum, especially for eastern EU members. Based on these figures, it is realistic to assume that each sides knows that an erosion of the relationship between Switzerland and the EU would be detrimental to both. The question now becomes how to move forward.

Competitiveness is key

Switzerland wanted an IFA so it could strengthen its competitiveness by gaining even better access to the EU’s internal market. But adopting excessive regulations and giving up some sovereignty could just as easily weaken Switzerland’s competitive position.

Deregulating the domestic market could also boost Switzerland’s competitiveness.

EU market access is by no means the only way of increasing Swiss competitiveness. Other options include further opening its economy, for example by abolishing all tariffs on trades and services – such a proposal is currently working its way through the legislative process. It could also join different free-trade coalitions, or better position itself internationally as a trade partner.

Deregulating the domestic market could also boost competitiveness. Influenced by the EU, Switzerland has adopted new economic regulations. The costs associated with such red tape amount to about 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, or more than 60 billion euros per year. Cutting these costs would free up means and entrepreneurial spirit, which in turn would increase competitiveness.

However, there are still several ways Switzerland and the EU can move forward. The Bilateral Agreements are, as mentioned, still in place. And in the medium term, it could be possible to renegotiate them.

Scenarios

The following scenarios for Switzerland to maintain or increase its competitiveness are possible, and none of them are mutually exclusive.

There is still a lot of room in the Swiss domestic market to increase competitiveness. On one hand, Switzerland is one of the most innovative economies in the world. On the other, its economic efficiency is faltering. This divergence shows that it is not realizing opportunities for value creation. The country can increase its competitiveness in the short term by reducing unnecessary regulatory costs and sponsoring more programs to release entrepreneurial energy.

Switzerland can also increase its competitiveness by improving its international position. One way to do this is focusing diplomacy on the country’s interests, reviving the policy of “good offices” (resolving international conflicts) or building international alliances of similarly thinking, liberal, low-tax countries. This is a medium-term scenario.

The free trade agreement dates to 1972. Updating it would not create complete market access, but it would at least secure parts of the cross-border exchange. The research programs – for example, Horizon Europe and Erasmus+ – can also be negotiated in this step and at least secured. This, too, is a medium-term scenario.

Switzerland and the EU could – after a pause in negotiations – again, seek a framework agreement. This is a long-term scenario in which Switzerland can leverage strengths in its negotiating position (such as the cohesion contribution, electricity transit, the integration of value chains in the area close to the border) against EU requirements, namely in the area of dispute resolution, and reach compromises.