ISIS keeps dwindling in Syria

Islamic State once controlled about a third of Syria. But it has been so devastated by a global anti-terrorism coalition that its ability to survive in the nation is in question.

In a nutshell

- Islamic State has failed to establish an international caliphate

- The organization is capable of sporadic attacks and localized violence

- With the Middle East less promising, ISIS is making inroads elsewhere

The Middle East, the cradle of armed jihadism, has become the scene of its mutation. Islamic State, also known as ISIS or Daesh, has reorganized itself since its military defeat in 2019, curtailing a 15-year run of terror in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere.

Radical jihadists have been forced to admit that the model devised by al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who was killed in 2011 by American forces, does not work. Bin Laden envisioned a global organization that condemns the “evil” and “impure” to summary executions. Despite their enthusiastic use of these tactics, both Islamic State and al-Qaeda have failed.

As the ISIS caliphate collapsed, its survivors set up sleeper cells in its former Syrian strongholds of Raqqa and Palmyra, and in smaller urban centers such as al-Bab. Each cell consists of safe houses to hide leaders, a mailbox for messengers, a warehouse for weapons and ammunition and a war chest. The total ISIS war chest is estimated at $25 million. Between 2014 and 2019, the group was infatuated with its mission to create a state. Today it is fighting to survive. It collects money by force, holds merchants for ransom and assassinates people who get in the way. Its soldiers attack prisons in northern Syria to free experienced fighters.

Identifying locations of ISIS activity in Syria is complex. The group operates in scattered areas that stay in touch through messengers. Some areas are sanctuaries, such as the Badiya or Syrian Desert, prized for its vast mineral wealth, where training camps can be set up and money can be earned by attacking oil drilling sites. And then there is territory where its intervention can be described as opportunistic, such as in Daraa, the birthplace of the revolt against President Bashar al-Assad in 2011.

ISIS has established itself in the region because of impoverishment and insecurity. Many fighters have been killed and others arrested. One of them revealed that he had been promised a monthly salary of $400, a substantial amount in Syria, to commit acts of violence.

Read more on Syria

Ending Syria’s tragedies

Bringing Assad in from the cold

Structural decay

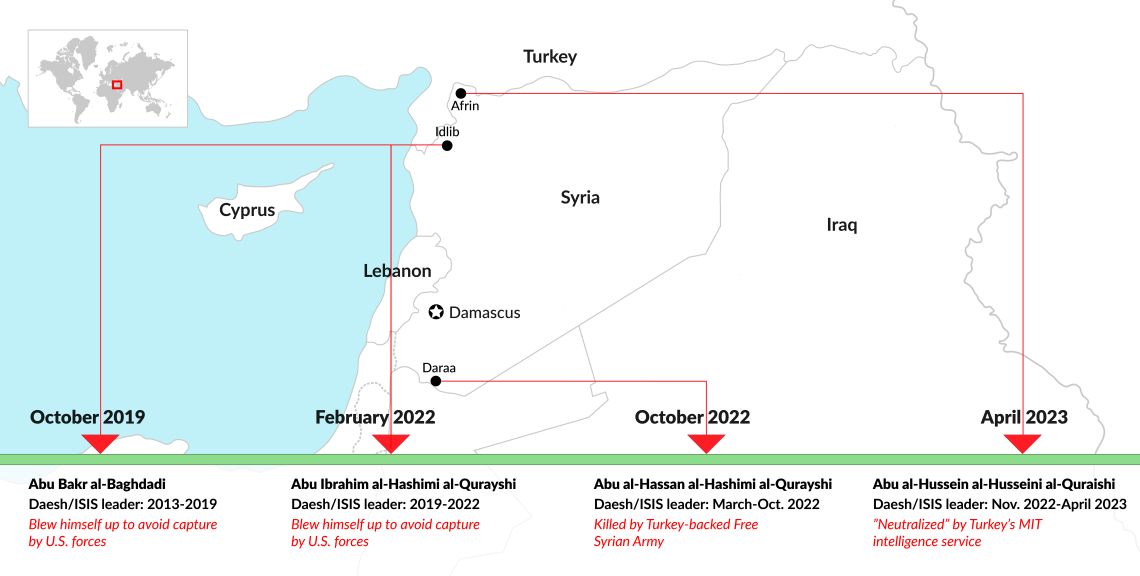

Once centralized around a leader and a Shura Council, ISIS now looks like a weakened organization. International counterterrorism forces have taken out its head four times and now the leadership structure struggling to revive itself. The most recent leader, Abu al-Hussein al-Husseini al-Quraishi, is or was an unknown. Turkey claimed on April 30, 2023, to have killed him in an anti-terrorist operation, but doubt remains. What exists now may be a collective leadership rather than reliance on a single leader. The aim of such an organizational model would be to evade anti-terrorist strikes while sending a message of resilience to the fighting base. This is a victory for the West, which has succeeded in structurally weakening the group and establishing the idea that any activist who rises to a position of responsibility will sooner or later be eliminated.

The organization maintains the appearance of a pyramidal structure. Arrests have enabled the identification of several functions: head of sector, head of intelligence, head of a sleeper cell, head of a training camp, planner of attacks, logistics manager, messenger, information office operator and fighters. There is no evidence, however, of a strong top-down command. Even at its peak, efficiency was rarely found in flashy organizational charts, which were mostly for show.

Disjointed leadership, declining terrorist incidents

Although forced to constantly reorganize, thereby remaining weak, ISIS maintains two operational hallmarks: a willingness to carry out massive attacks and a penchant for hyper-violence. Its attack on a prison in the northeastern Syrian city of Hasakah in 2022 was indicative of its deadly ambitions. The operation, with perhaps 300 prisoners released and 346 attackers killed, shows that the group has not given up on its excesses and has not learned any lessons. It faces a recruitment problem in rebuilding its ranks and building loyalty and professionalism. The Hasakah attack, spectacular as it was, confirmed the limits of its capacity.

The United Nations has reported a decline in ISIS attacks in Syria, an assessment confirmed by the Global Coalition Against Daesh, which has recorded a 55 percent drop in operations in 2022. While these figures present an undeniable reality, it is important to stress that they do not include failed or aborted operations nor the small-scale violence that takes place daily in the triangle of Palmyra-Deir Ezzor-Abu Kamal, where physical threats, robberies, kidnappings, assassinations and the planting of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) are common. ISIS still has the capacity to cause damage through unorthodox attacks, including from opportunistic actions such as the escape of 20 or so prisoners who took advantage of disorganization due to the earthquake of February 6, 2023, to escape from Rajo prison in northwestern Syria. They are likely to join the group’s cells.

Combining large-scale attacks with neighborhood harassment is likely indicative of a disjointed chain of command, between a leadership obsessed with large-scale warfare and autonomous cells running their small businesses through a mixture of gangsterism and theological tinkering.

Facts & figures

Eliminating ISIS leaders in Syria

Middle East is no longer an ISIS growth area

The group’s propaganda, available in 23 languages, produces supposedly spiritual sermons. The beheading videos remain, but they are fewer in number and far less scripted than before. Terror campaigns have declined significantly. ISIS no longer uses them as an overall strategy, but as an ad hoc tactic, both brutal and to the point.

Members cold-bloodedly slaughter civilians who have no theological or military interest. Since February, ISIS has killed around 100 civilians picking truffles in the Homs and Hama areas. The mushrooms provide small revenue to the poorest of the poor. Militants steal their harvests and put them on the market. Flocks of sheep are slaughtered to terrify the rural population and force them to declare their allegiance. The typical arrangement is safety for the villagers in exchange for donations of money and supplies to ISIS fighters.

Russia and the United States are conducting counterterrorism operations in the Syrian Desert, the U.S. forces being by far the most active. They work tirelessly to eliminate the organization’s key operatives like Hudhayfah al-Yamani, an operations planner, or, more recently, Mahmoud al-Hajj, head of intelligence and recruitment. These men, who are supposed to be experienced in clandestine life, made serious security errors that allowed them to be traced. The leader of ISIS’s Iraqi branch, Abu Sarah al-Iraqi, was killed in February, demonstrating once again the failure of the security services to protect their leaders.

The story of the neutralization of one ISIS leader, Abu al-Hassan al-Hashemi, is enlightening. As per usual practice, upon its arrival in the Syrian town of Jasim in 2022, the group began by eliminating local elites and setting up a Sharia court that sentenced residents to death. But the residents quickly allied themselves with opposition groups. Clashes broke out. When the beleaguered ISIS asked the people of neighboring Busra al-Sham for help, the response was negative. The fighting proved fatal for Mr. Hashemi and his security detail.

ISIS is holding out because the Levant, which includes part of Syria, is central to its theological discourse. Adherents believe it is where the Mahdi will establish the Kingdom of God at the end of time. But the specter of a split looms. Tensions that were underplayed during the organization’s heyday are now coming to the fore.

Structural tensions played out when the Syrian branch renewed its leadership without informing its Iraqi counterpart. A lack of unity and common goals became evident when the Iraqi branch refused to take part in the attack on al-Hasakah prison in 2022. The Iraqi branch also blames the Syrians for the bloody experience of the caliphate.

According to a former activist who defected from the group, there is an “urgent need to reposition the organization.” Indeed, the Middle East is no longer a growth area for ISIS. Cells attempting to operate in Israel have been dismantled. The Libyan branch, led by Abdulsalam Darkullah, has retreated to southwestern Libya’s Fezzan in the Acarus mountains. The commander is infiltrating fighters into the refugee flows reaching the Schengen area to carry out operations in Europe, taking advantage of a lull in the vigilance of European security services partly because of Russia’s war on Ukraine. There is nothing to suggest Mr. Darkullah’s aims will succeed.

Scenarios

In a less likely scenario, ISIS is not able to maintain its capacity to cause harm. It compensates for the decline in the number of operations with excessive brutality. It shrinks to nothing more than an outlet for a small number of nihilists, desperate and abandoned by the Syrian drama.

In a more likely scenario, being pursued by the Damascus regime, the U.S., the European Union and (to a lesser extent) Russia and Iran, ISIS minimizes its military efforts. It seeks to keep the level of the conflict low enough to exist without attracting the bombs of the international anti-terrorism coalition. Meanwhile, other franchises flourish in Africa, Central Asia and even India. ISIS becomes a flagship that slowly sinks as its flotilla sails in other seas and oceans.