Syria’s relentless war

Though the regime of President Bashar al-Assad now governs most of the country and ISIS has lost the territory, there is still no end in sight for the Syrian Civil War. Opposition groups control several provinces, and the complicated web of foreign interests has yet to be untangled.

In a nutshell

- Russia’s involvement cemented its influence in the region

- Attempts to resolve the conflict have failed

- Violence continues, supported by foreign interests

- Stability and reconstruction remain a distant dream

In Syria, the popular uprising against the regime of Bashar al-Assad has largely been quashed. Russia and the United States have declared several times during the past three years that they have won the war against terrorism in Syria and that the reconstruction of the country is now on the agenda. Yet none of the country’s manifold problems have found a solution.

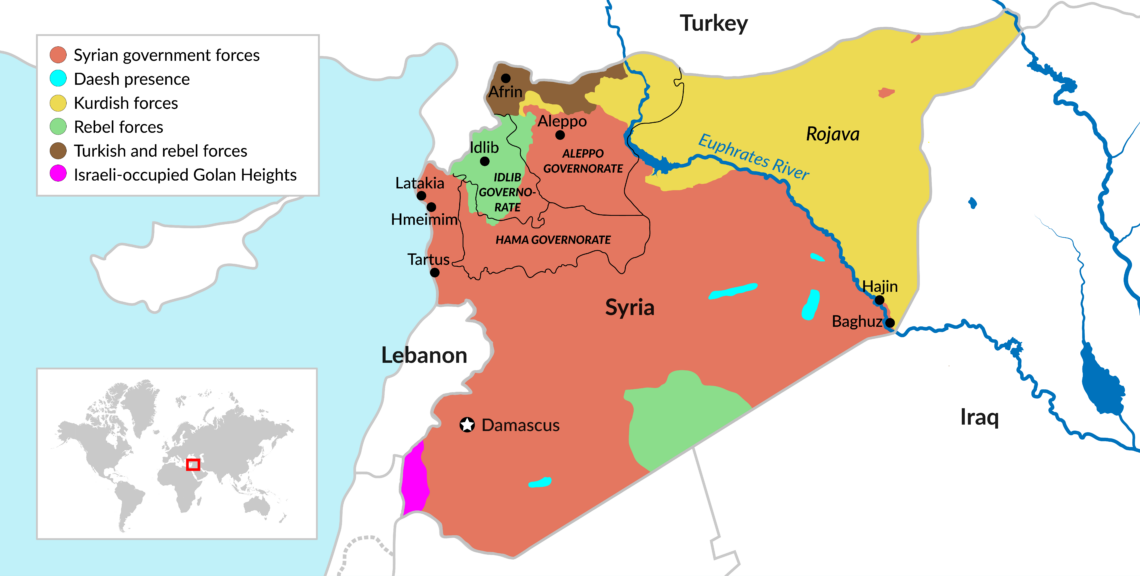

On one hand, Russia and Iran have saved Mr. Assad’s regime. The Syrian president now rules most of the country, having taken back territories conquered by opposition organizations and by Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh), which has lost its territory. On the other hand, fighting has not abated in parts of Syria, while a third of the country is not under the regime’s control.

Attempts to resolve the conflict – including the United Nations’ Geneva process, as well as the Astana process, led by Russia, Iran and Turkey – have failed. There is no progress toward a political solution and no attempt to bring back Syrian refugees – some 6.5 million of whom have left the country and another 6 million who are internally displaced. Daesh is down but not out: a recent video has shown that its leader, self-appointed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is still alive. With his companions, he roams the deserts of Syria and Iraq and his militants still carry out terror attacks, though mainly in Iraq. There is no indication of a return to normalcy in the foreseeable future.

Russia on top

Russia appears to have gained most from the conflict. As long as President Assad remains in charge, Moscow will retain its significant influence in Syria and will be a major factor in the lengthy reconstruction, expected to draw in billions of dollars in foreign investment. It will keep exploiting the gas and oil fields it has largely taken over. Its military presence is bolstered by a 49-year lease on the Tartus naval base and its control over the Hmeimim airfield near Latakia, ensuring its influence in the Mediterranean basin. By taking part in the fighting, the Russian army has acquired valuable experience. It has also tested new weapons – a total of 210 according to Russian sources. But it needs the situation to stabilize to maximize those assets.

There is no indication of a return to normalcy in the foreseeable future.

A third of the country – from its border with Turkey to that with Iraq – is still in the hands of Kurdish organizations backed by the U.S. They have set up a would-be autonomous federation known as Rojava. Turkey considers them hostile, fearing they could join forces with its own outlawed Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) to fight for independence. To prevent them from collaborating, Ankara invaded in August 2018 and occupied the Afrin district, in the western part of Rojava. Fierce fighting led to a huge exodus: some 200,000 people fled the area. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan then handed partial control to the Syrian Islamic rebels he has been backing. They are reportedly merciless in quelling resistance. Now, Turkey is trying to establish a 20-mile safe zone in Syrian territory along the border, a move vehemently opposed by Damascus, which considers it an illegal occupation.

Then there is Idlib, a province of some 6,000 square kilometers to the northwest, bordering Turkey. With rural areas of the Aleppo governorate to the east and the Hama governorate to the south, it is held by opposition forces. Some three million people live there, half of them arriving in the past two years following the surrender of some rebel groups to President Assad’s army, which has been backed by Russian air raids and pro-Iranian militias. Told to join the Syrian army or leave, they and their families opted for “exile” in Idlib. The province is under the control of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), an offshoot of the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front. Together with some smaller rebel groups it can muster 50,000 resolute and well-equipped fighters. According to the now-defunct Astana agreement, Idlib was to be one of the four “de-escalation” zones. The other three were conquered by Assad with the help of Russia and Iran, which blatantly ignored the agreement. Idlib stood firm.

Turkey losing out

In September 2018, Ankara brokered a deal with Russia. The goal was to avoid renewed fighting in Idlib, which would send hundreds of thousands of refugees across the border to join the three million Syrians already in Turkey. Moscow’s end of the deal was to prevent President Assad from attacking Idlib, while the Turks would set up observation posts around the province to avoid another flare-up and work to achieve a nonviolent solution.

Nevertheless, a few weeks later Syria renewed its attacks with the help of devastating Russian air strikes. According to the London-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, President Assad is once again targeting heavily populated areas and does not hesitate to drop barrels of explosives. Casualties are mounting but the media have lost interest. There are accusations that chemical weapons have been used, but these are yet to be proven. HTS fighters are holding their ground and have even sent drones armed with explosives to attack Russian bases. Rebel forces backed by Turkey appear to be assisting HTS.

Facts & figures

Syria: Still at war

Turkey is in a difficult position. Wanting to neutralize the Kurds and set up a buffer zone, it finds itself at loggerheads with the U.S., which is assisting the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) mainly comprised of Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG. They are the ones that spearheaded the fight against Daesh, defeated the jihadis, established Rojava and took over the north of Syria.

Recently, the Kurds have engaged in a dialogue with President Assad, aiming to reach an understanding about some form of autonomous status. Both parties view the Turkish presence in the region as an occupation they want to end.

Ankara, which had originally insisted on President Assad’s ouster as the key to a solution, changed its stance and joined the Astana forum with Russia and Iran. However, it became apparent that its interests do not align with Russia’s.

Both are intent on restoring Syrian control over the entire country, allowing the president to reassert his authority and supervise reconstruction efforts and the return of refugees. Turkey was convinced that Russia would be on its side. Indeed, Moscow had evacuated its outposts in Afrin, letting Ankara take over. To further their cooperation, President Erdogan decided to acquire Russia’s state of the art S-400 air defense system. This led to further tension with Washington, Ankara’s NATO ally, which is now considering imposing sanctions on Turkey for introducing nonstandard equipment. Furthermore, Turkey may lose its membership on the council supervising production of the American F35 stealth fighter. The U.S Air Force has already stopped training Turkish pilots on the aircraft. Turkey’s overall standing in the conflict has been seriously eroded.

Daesh defeated?

As for Daesh, the reason for the international intervention in Syria and the creation of a 79-country strong coalition under U.S. command – has it really been defeated? Can it, phoenix-like, rise again? On December 14, 2018 the SDF proclaimed it had retaken the town of Hajin in Syria’s northeast. It was Daesh’s last stronghold, though the SDF admitted that ISIS still held several villages close to the Iraqi border.

The move to withdraw the troops met such strong opposition that President Trump changed his mind.

President Trump hastened to declare five days later that Daesh had been “100 percent defeated.” He also made the surprise announcement that he would bring home the American forces providing the SDF with intelligence and support – an estimated 2,000 troops whose presence demonstrated Washington’s political determination to prevent Turkey and Iran from penetrating further into the region. Previously, he had stated that American troops would remain until pro-Iranian militias and their Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps advisers had left. The move to withdraw the troops met such strong opposition from Defense Department officials and from Israel that he changed his mind. Today, Washington’s Syria policy remains unclear.

Last February, there was a new clash with Daesh. The SDF had to regroup and launch an offensive against its center of operations in Baghuz, near the Iraqi border. They took the city after a month of fierce fighting, during which some 20,000 residents had fled. On March 23, it was the SDF’s turn to announce “total victory” and the definitive elimination of Islamic State. But thousands of its militants are still scattered throughout the desert areas of Syria and Iraq. Its leaders, including Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, are still alive. Their propaganda machine is still working and they direct or inspire terror operations, mainly in Iraq, where the prime minister proudly declared victory over Daesh in October 2017 after Mosul was retaken. In a surprise visit to the Hmeimim air base in December 2017, Russian President Vladimir Putin also claimed victory, though Russia had not been part of the coalition and had mostly fought against opposition forces.

Thousands of terrorists have been taken prisoner in Syria and Iraq. Some have been executed, but many are in prison camps with their families. The fate of jailed foreign volunteers divides Europe: should they be readmitted in their home countries?

Iran: regional rise

Iran was a major contributor in salvaging the Assad regime by sending its proxy Hezbollah and its Shia militias to fight alongside the Syrian army. Tehran did not do this for the sake of President Assad. It wants to gain a stronger foothold in Syria and use that country as an advance base for continuing its subversive activities in the Middle East and threatening Israel – attempting to weaken it through terror operations until it can be destroyed. Israel is watching closely and taking steps to eliminate the threats through hundreds of bombing raids on Iranian launching pads for missiles and drones, on Shia militia encampments and on hangars where missiles awaiting transfer to Hezbollah in Lebanon are stocked. Israel has been successful so far. Russia and Syria are unhappy about Iran’s activities, which hamper efforts to restore calm and stability, a prerequisite for reconstruction efforts. Nevertheless, they continue to cooperate with Tehran for want of another option.

Continuation of the war could cause more chaos, more destruction, more casualties and create thousands more refugees.

The UN Security Council has passed no less than 23 resolutions on Syria over the past eight years, the most important being resolution 2254 of December 18, 2015. It demands that the country’s territorial integrity be preserved, an interim government with the participation of all relevant parties be formed within six months to draft a new constitution, and elections held within 18 months. Adopted unanimously, the resolution was never implemented. Opposition organizations refuse to sit down with representatives of President Assad and demand his ouster. Russia and Iran launched the Astana forum to further their own solutions and were joined by Turkey. They tried and failed to bring all of Syria’s relevant political forces together in a committee to draft a constitution.

The goals set down by Resolution 2254 appear more unattainable than ever. Continuation of the war could cause more chaos, more destruction, more casualties and create potentially hundreds of thousands more refugees, many of whom could attempt to find a better future in Europe. President Trump does not seem to have a clear policy and will probably refrain from ending his military presence in Syria. But he will do nothing else, unless a chemical weapons attack by the Assad regime triggers another global outcry.

Russia and the U.S. are barely on speaking terms, though they continue to make halfhearted efforts at the UN to find a suitable political compromise. In fact, according to a White House announcement, U.S National Security Adviser John Bolton is coming to Jerusalem in late June to meet with his Israeli and Russian counterparts to discuss regional issues, reportedly including Syria and Iran. The latter has no intention of withdrawing from Syria and is still determined to extend its domination in the name of Shia Islam over the Middle East, a goal Israel will do its utmost to prevent.

Despite the fall of Daesh, the call for an Islamic takeover of the world and the creation of a caliphate still resonate throughout the Arab world. It is promoted by the Muslim Brotherhood and dozens of jihadi groups in the Middle East, Asia and Africa. Somewhere, sometime, someone will once again raise the flag of an Islamic state.

As things stand, a bleak future awaits war-torn Syria. Reconstruction is a distant dream and refugees are bereft of hope. Low-grade fighting will continue, with occasional flare-ups that could potentially ignite other conflagrations in the region.