Looking for the best tax code

Modern governments collect an increasing proportion of their countries’ output in taxes, which spreads inefficiency and economic stagnation. The drivers of this process can be neutralized, and the distorting impact of taxation mitigated with better tax-system design. Among OECD member states, there are examples of solutions to emulate.

In a nutshell

- Tax codes can be dauntingly complex, but the key issue is simple: What percent of the economy is taxed?

- A well-designed tax code can minimize the economic losses inherent with any tax system

- The composition of taxes that comprise the revenue system, the design of each levy and the tax rate are all equally important

The rates and design of a country’s tax system can have a significant effect on economic performance and citizens’ well-being. A tax structure with low rates that does not burden saving and investment will facilitate market-based decision-making and stronger economies.

Economists like to obsess over the details of how a tax is designed and the structure of the various revenue sources. However, the details often distract from the most fundamental question: What percent of the economy is taxed? Tax revenue as a percentage of its total output (the gross domestic product, GDP) represents an average, countrywide tax rate and shows how much of the economy is driven by politics rather than markets. As the size of government increases, individuals’ well-being is diminished because government waste scares resources that are better used by individuals living their own lives.

Overall burden

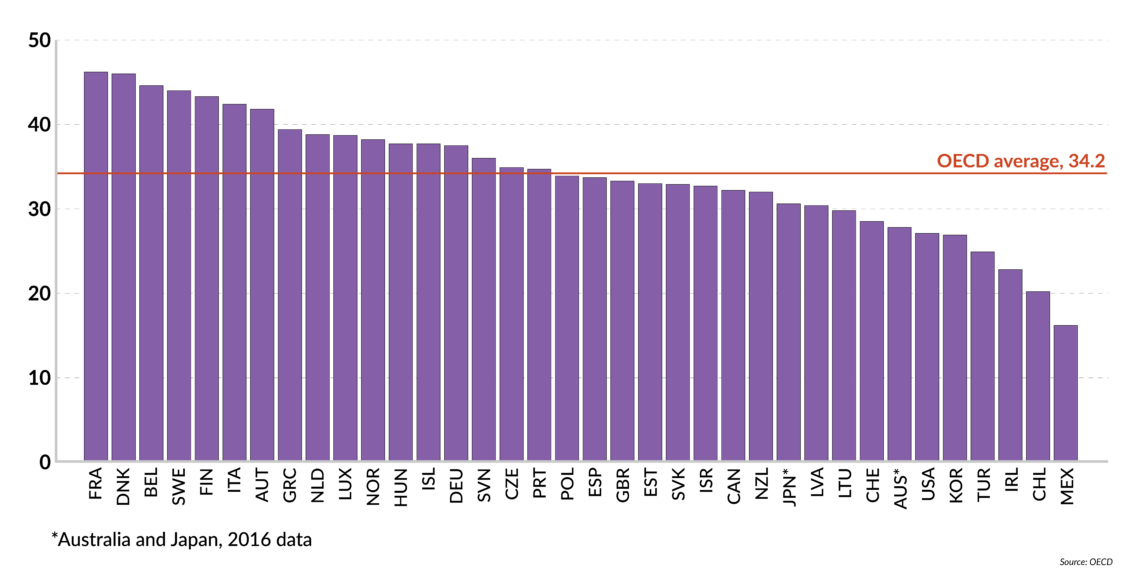

Across the 36 member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), governments on average collect 34 percent of the countries’ GDP. Many of the most prominent European Union countries collect much more than the average. In France, the government collects 46 percent of the economy in taxes, in Sweden the figure is 44 percent, in Italy it is 42 percent, in Greece 39 percent and in Germany 37 percent. Falling furthest below the average are Mexico (16 percent), Chile (20 percent) and Ireland (23 percent).

A low overall tax burden is an essential component of a good tax system. Even with the best design, taxing 40 percent of all activity will have significant economic consequences that materialize as fewer opportunities for workers. However, a well-designed tax code can minimize the economic losses inherent with any tax system.

Facts & figures

Tax-to-GDP ratio compared to the OECD, 2017

The composition of taxes that comprise the revenue system, the design of each levy and the tax rate are all equally important. In the OECD, individual income taxes, payroll taxes, and value-added taxes (VAT) make up the largest portions of most countries’ tax revenue. Accounting for a smaller share of the revenue, corporate income taxes are especially economically destructive, as are tariffs and other excise taxes.

Marginal tax wedge

Income and payroll taxes (whether paid by the employee or employer) are ultimately wage taxes and make up the single largest share of tax revenue for OECD countries. The marginal tax wedge (which represents how much tax a worker must pay on the next dollar of income earned) across the 23 EU-OECD countries on workers who make two-thirds the average wage was 50 percent in 2018. So, if a worker is considering driving for Uber on the weekends for a little additional income, the marginal tax wedge shows how much of that extra income the worker would be allowed to keep.

Switzerland stands out as the lone place where workers pay their taxes directly.

In France and Belgium, marginal rates on below-average incomes are 70 percent and 68 percent, respectively.

Workers earning above the average wage pay even higher taxes than low-wage workers in most countries across Europe. The marginal tax on wages is above 50 percent on workers earning 167 percent of the countries average wage in 13 EU-OECD countries. Among OECD countries, Chile has the lowest marginal tax wedge of 10 percent, significantly lower than Mexico (28 percent) and Korea (32 percent). Three countries have marginal taxes above 60 percent. Sweden’s top rate is shy of 70 percent for workers earning 167 percent of the average wage.

High marginal taxes reduce the incentives for people to take an extra job, start their own business, or work as hard to get a raise or promotion. People across Europe work shorter hours, take more vacation and are less entrepreneurial not because they do not want to work more. It is so because their high-income taxes penalize extra effort.

Government tricks

One problem almost every OECD country has in common is that income and payroll taxes are withheld by the employer, conscripting businesses as tax collectors. Switzerland stands out as the lone example of a place where workers pay their taxes directly. Once a year, Swiss workers write a single check to the government for their full tax bill. They know precisely how much their government costs them.

Taxation that eschews withholding is part of a more comprehensive governance structure which includes one of the most awe-inspiring budgeting systems in the world. The Swiss rely on fiscal rules that are constrained by spending and tax limits. Pegging federal spending and debt to GDP, the government of the Swiss Confederation is able to follow prevailing economic cycles — spending more when the economy is down and less when growth is strong.

A tax system with automatic withholding makes strict fiscal rules harder to enforce. Most taxpayers do not realize how much they pay in taxes. Proponents of automatic deduction argue that it is the only way for the governments to raise enough tax revenue without people crying foul. They are exactly right. Tax withholding removes an important political constraint on government power to tax and spend at ever-increasing levels.

Another way governments hide the taxes we pay is through indirect taxes, collected and remitted by businesses. Across the OECD, consumption taxes on goods and services are the largest single source of revenue, comprising 33 percent of government funding. The United States is the only country in the OECD that does not use a value-added tax (VAT) that is collected by businesses at each phase of production. The U.S. instead relies on a retail-level sales tax, imposed by most states.

Consumption taxes

Consumption taxes are highly efficient, as they minimize economic damage to saving and investment. Saving is delayed consumption, so tax systems that only tax income when it is spent on final goods, are more economically neutral. Income taxes, on the other hand, often double-tax income that is saved, which discourages saving and the resulting economic growth.

The most destructive taxes have high rates and discourage saving and investment.

Even though consumption taxes are in the abstract a good tax, the addition of VATs across the OECD is closely associated with more spending and larger governments. The decision to add new, more efficient fees to a revenue system must be weighed against the propensity for governments to exploit that new source of revenue beyond its original purpose.

In countries with VAT, the goal should be to keep rates low and tax all goods and services equally. On the first account, Canada (federal VAT rate of 5 percent), Switzerland (7.7 percent), and Japan (8 percent) have the three lowest rates in the OECD. Luxembourg and New Zealand have two of the most comprehensive, broad-based VATs, with Japan following closely behind. The most comprehensive VATs include the largest share of goods and services in the tax base so that all consumption is treated equally, rather than applying special exemptions and lower rates to politically favored products. Mexico and Italy round out the narrowest, least efficient VAT systems in the OECD.

The most destructive taxes

Although a relatively small revenue source for most OECD countries, the corporate income tax is one of the more economically harmful taxes on which countries regularly rely. In 2019, Hungary (9 percent), Ireland (12.5 percent) and Lithuania (15 percent) had the three lowest corporate tax rates in the OECD. France and Portugal are the only two countries that have rates above 30 percent. Even after the 2017 tax cut, the U.S.’s combined corporate rate (including sub-federal taxes) is still above the OECD average of 23.5 percent, at 25.9 percent.

The structure of the corporate tax is just as important as the rate. Although Estonia does not have the lowest corporate tax rate (20 percent), the burden is assessed on a cash-flow basis and the system has relatively few complex incentives for special interests. These features make it the most competitive corporate tax arrangement in the OECD, according to the Tax Foundation. The most destructive taxes are those that have high rates and discourage saving and investment. Many countries across Europe demonstrate just how damaging poorly designed charges can be.

There are also leading examples of good tax features.

In this respect, countries should strive for low tax levels like Hungary, overall low wage taxes like Chile and no withholding like the Swiss. Japan stands out as having a low- but well-performing consumption tax and the corporate taxes of Hungary and Estonia should be a guide for business taxation. At the highest level, a good tax system should raise the revenue necessary to fund a limited government while not changing an individual’s economic decision-making.