Big government means high taxes

There is a growing myth that the rich are not paying their fair share in taxes and that the middle class is therefore overtaxed. High-income taxpayers across the OECD pay more than their share of the national income. The blame for heavy tax burdens in Western democracies lies with the voters, who have chosen a larger government.

In a nutshell

- Western electorates have consistently voted for big government spending programs

- Income taxes in OECD countries are highly progressive, with the rich paying more

- Once payroll and consumption tax is factored in, the burden shifts to the middle class

- The best way to boost growth is smaller government and lower tax burdens for all

There is a growing myth that the rich are not paying their fair share in taxes and that the middle class is therefore overtaxed. This is not the case. High-income taxpayers across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) pay more than their share of the national income.

Voters in Western democracies have consistently voted for larger government. Big governments require high and burdensome taxes, on everyone. Unless voters become willing to scale back the size and scope of state activity, taxes will have to remain high across the board.

Taxes – and the spending that they fund – have been at the heart of recent political moments. The French Yellow Vest protests began with complaints about a new tax increase on motor fuels. In the United States, some politicians are calling for higher tax rates on the wealthy to fund a European-style welfare state. OECD countries vary widely in how they structure their taxes, but nowhere are there income groups skating by without paying much tax. Everyone is overtaxed – if anything, the rich are paying more than their fair share.

Bite size

When comparing tax systems by country, it is crucial to consider these systems’ different components. Total revenue collected is the most straightforward. The composition of that revenue stream (what taxes are collected and at what rates) is equally important. In the OECD, individual income taxes, payroll taxes, and value-added taxes (VAT) comprise the bulk of most countries’ tax revenue.

The total level of taxation is useful because it can serve as an approximation of a country’s average tax rate and shows how much of the economy is driven by politics rather than markets. Across the OECD, governments collect 34 percent of their countries’ total output (GDP) in taxes. Many collect far more; France’s tax take is 46 percent of total output, Sweden’s 44 percent, Italy’s 43 percent, Greece’s 39 percent, and Germany’s 37 percent. The United Kingdom and the U.S. fall below the average at 33 percent and 26 percent, respectively.

When governments tax away more than a third of output, they have expanded beyond their core competencies.

As public spending increases, the well-being of individuals tends to decrease because governments waste scarce resources that would be better used by individuals living unencumbered lives.

Taxes themselves impose significant economic costs, which compound as marginal tax rates increase. When a government taxes away more than a third, and up to half, of productive output, we can safely say that it has expanded beyond its core competencies. That now applies to most of the OECD. Many countries are borrowing beyond their current tax revenue, indicating that rates will need to increase even further in the future. By these metrics, we are all overtaxed.

Revenue composition

The composition of tax revenue is also important. OECD countries rely on personal income taxes for about one-third of their revenue. Income taxes tend to be the most noticeable and politically salient parts of tax codes. They are also the most progressive component of these tax systems, since higher incomes are taxed at higher rates.

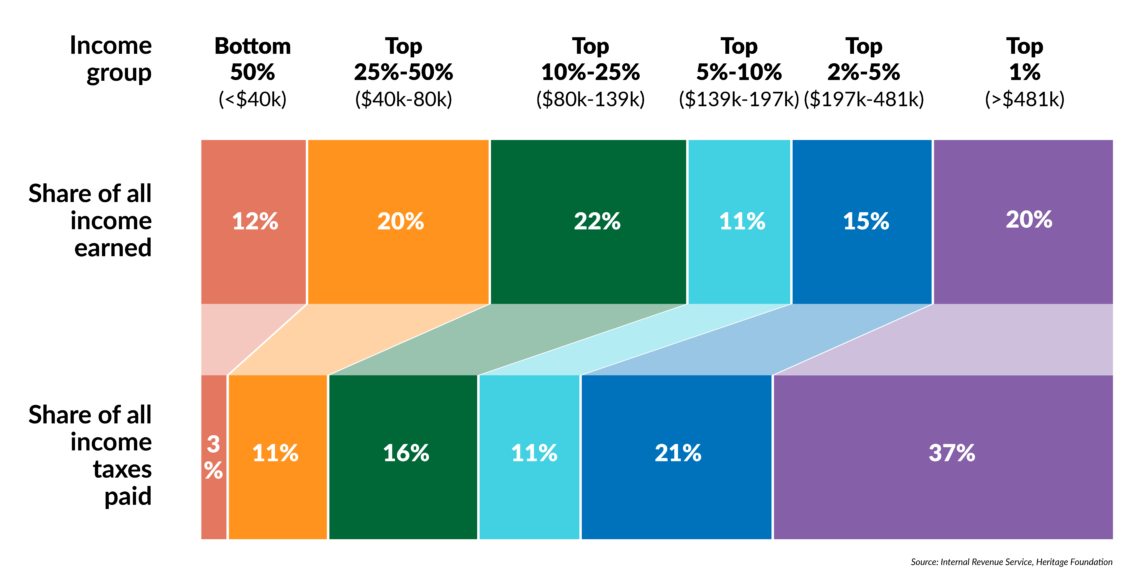

Among the countries that rely most on income taxes for revenue, the U.S. has one of the most progressive systems. In 2016, the top 1 percent of U.S. income earners – those earning at least $500,000 – received 20 percent of all income while paying 37 percent of federal income taxes. The top 10 percent earned 46 percent and paid almost 70 percent, respectively. The bottom half paid just 3 percent of income taxes, but earned 12 percent of the national income.

Canada’s income tax is less progressive, but it still escalates for higher incomes. The top 20 percent of income earners in Canada received 49 percent of all income and paid 64 percent of the income tax. Denmark levies about 20 percent of the poorest 10 percent’s income in 2013, rising quickly to an effective tax rate of 40 percent on the lower middle class and 60 percent on the top 10 percent. In the UK, the top 10 percent of income earners pay 59 percent of the income tax, while the bottom half pay less than 10 percent. Denmark and the U.S. are the OECD’s outliers, relying on personal income tax for about half of their tax receipts. In Canada, the corresponding figure is 36 percent; in the UK, it is only 20 percent.

Payroll or social insurance taxes are another popular income tax in the OECD countries. These levies most often fund some form of direct benefit programs. They are usually designed to start out as progressive levies, then top out for higher incomes. Because these taxes go directly to benefit programs and are usually described as “contributions,” they are not perceived as a personal income tax. This is a mistake since, like any other income tax, they change work incentives and act as a drag on the economy.

After combining income and payroll taxes, every OECD country maintained a progressive average tax burden on workers in the middle of the income distribution.

Progressive bias

Most countries also have consumption or value-added taxes. Because these taxes are paid on all purchases, exposure to a VAT tends to be much more evenly distributed across all incomes. As a percent of income, consumption taxes are regressive, as lower-income taxpayers pay a larger share in relation to their incomes. The U.S. is unique in not having a VAT, but most U.S. states have sales taxes, which have a similar effect.

After combining the effects of income, payroll, VAT and other taxes, the tax burden is still highly progressive across the OECD. In the UK, the bottom half of income earners paid about 20 percent of their income in taxes this year. By comparison, the cumulative effective tax rate for the richest 10 percent is over 45 percent. In the U.S., the lowest income groups pay a 16 percent effective rate, rising to 31 percent for the top income groups.

Because of VAT and payroll tax structures, France’s tax system is much less progressive. Effective tax rates increase quickly at the bottom, then top out at about 45 percent for the middle class.

Inconvenient facts

There is not a single OECD country where the rich are not paying their “fair share.” In each case examined, high-income taxpayers pay a larger share of taxes than their portion of the national income. Moreover, yearly income is a poor measure of wealth, and many of the seemingly rich only qualify in the year they sell their business or realize a one-time gain. If anything, the rich are overtaxed.

The modern welfare state requires high and burdensome taxes. There is no escaping this fact. Until voters wish to scale back government’s size and scope, taxes will have to remain high.

Most national income is earned by the middle classes, which must be heavily taxed if large welfare states are to work.

Another inconvenient fact is that the rich do not have enough annual earnings – or wealth for that matter – to fund another dramatic expansion in government spending. The bulk of national income is earned by the middle classes, which must be heavily taxed if large welfare states are to make their finances work.

Even if voters decided the rich need to pay more than their fair share, experiments with high taxes on the wealthy have generally failed. In the high-tax Scandinavian countries, the super-wealthy avoid about 25 percent of their taxes by shifting income to other countries. When France tried to tax large yachts, their owners just sailed away to marinas in Spain and Italy. Very little revenue was raised, and the main effect was to hurt French workers and businesses.

Over the past few decades, European counties have steadily moved away from taxes on wealth and punitive income levies. A study by the OECD found that past attempts to tax wealth “frequently failed to meet their redistributive goals” and encountered significant administrative problems.

High taxes drain resources from building strong economies through work and investment and redirect them to tax avoidance through costly lawyers and accountants. When the rich and the middle classes are overtaxed, the answer is smaller government and lighter tax burdens across the board.