The irrelevance of ‘tight’ U.S. monetary policy

Promises by the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy will not soon reverse the consequences of recent U.S. fiscal policy or improve its economic outlook.

In a nutshell

- U.S. interest rates remain low across the board

- Investors will continue to buy equity

- Promised rate hikes will not make a difference quickly

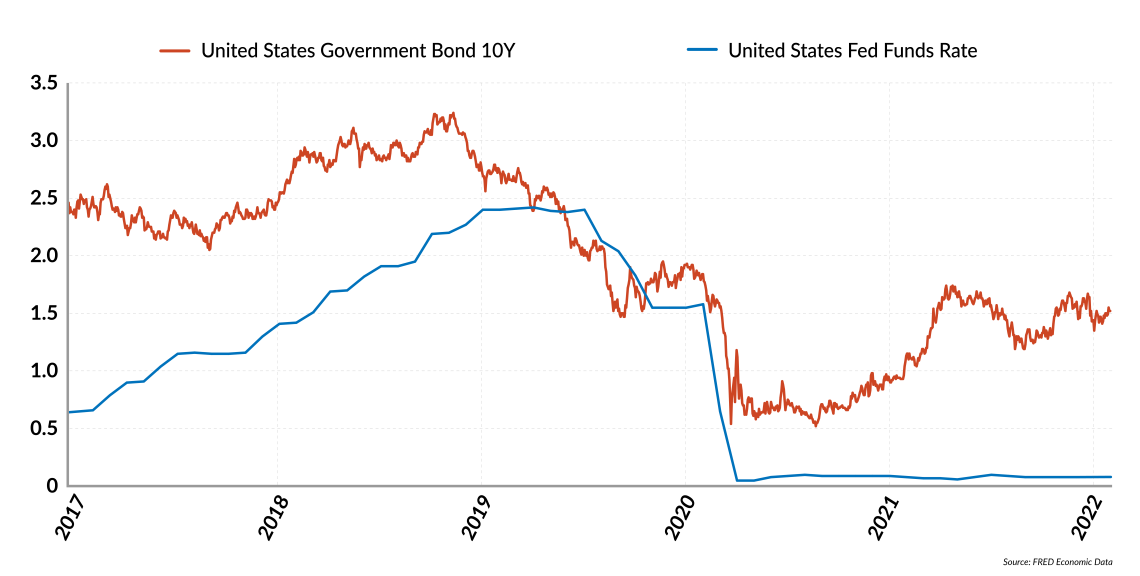

In recent weeks, United States monetary policy has become a major source of uncertainty. Inflation reached 7.5 percent in January 2022, while interest rates on the 10-year note rose from about 1.4 percent to about 1.8 percent during that month.

The latter could be considered a big spike, but in reality, it is probably less than the rise in inflationary expectations seen at the end of 2021, and certainly not enough to make real interest rates positive (and they well below early 2019 levels).

One might argue that interest rates on government bonds are being manipulated by the central bank, and that they are still useful to predict the cost of servicing the public debt and assessing the direction of monetary policy, but that interest rates on Main Street are different. Not quite: at the end of January, the 15-year (fixed) mortgage rate was 3.2 percent and the rate on four-year car loans was 3.5 percent. The situation is similar in the corporate bond market. Put differently, while the spread between these Main Street figures and the yield on treasuries has risen, all rates remain very low across the board.

The explanation is straightforward. Central banks – and the Federal Reserve is no exception – have been financing the public and the private sectors. As long as commercial banks can borrow at low interest rates from the central bank or at even lower rates from depositors, they are perfectly happy to lend money to the private sector at rates not much higher than zero, and still make a profit.

Rising rates?

The Fed recently announced a change of tack to tighter monetary policy. Financial markets have wobbled, and stocks and bonds have taken a beating. Shareholders have anticipated higher financial costs and, therefore, lower economic growth in general and lower corporate profits in particular. Bondholders have dumped assets in the hopes of later buying higher-yield equivalents.

In theory, all of this is sensible, and has prompted commentators to argue that investors should brace for choppy waters and move assets from equity and bonds to safe assets such as gold, real estate, inflation-indexed securities. Yet it is not clear whether this wait-and-see strategy is actually defensive, coming from catastrophic predictions about the future (low growth, high inflation, soaring interest rates); or whether it reflects a buy-the-dip opportunism. The rest of this report tries to shed light on these two scenarios.

We start with two preliminary remarks, the first observing the Fed’s behavior. The traditional rationale for announcing a change in monetary policy before implementing it is to encourage transparency and the desire for a gradual adjustment. It is believed that individuals should know in advance what the policymaker plans, so as to adjust their behavior. This sounds reasonable in the realm of regulation and taxation, but is less so in financial markets, where expectations about the future are already taken into account immediately. One wonders, then, why the Fed did not raise interest rates the moment it believed that inflation was persistent and exceedingly high.

Facts & figures

U.S. interest rates and bond yields

The second observation concerns investors’ behavior. Despite the Fed’s promise to tighten monetary policy, investors seem to pay attention to future growth prospects, not interest rates. Their actions suggest they do not much care what the Fed does as long as real interest rates remain deeply negative and growth is satisfactory. To be sure, the S&P 500 fell 5.5 percent in January 2022. That’s bad news for those with a lot of equity in their portfolios – but it’s far from a disaster, especially since the index rose 27 percent during the previous 12 months.

Our early conclusion is therefore that the alleged tightening of – or promise to tighten –monetary policy should not be taken too seriously. First, corporations and consumers are not going to change their plans if the cost of borrowing moves from 3 to 4 percent and inflation remains substantial. Inflation would have to quickly drop to zero to transform a 4 percent nominal interest rate into a source of problems – and it will not.

Second, the very fact that the Fed keeps making announcements and promises but delays action means that policymakers are groping for solutions, and that short-term contingencies are trumping strategy for now. Finally, one suspects that the actual goal of monetary authorities lies not in fighting inflation, but in signaling its concern for inflation. If the purpose is to make Wall Street happy and keep Main Street quiet, pronouncements are better than action.

Scenarios

The defensive narrative discussed above follows from a rather dim view about the future. After having dropped 3.4 percent in 2020, U.S. gross domestic product during 2021 grew by 5.7 percent, and the International Monetary Fund predicts 4 percent growth for this year. This is perhaps optimistic, since companies seem reluctant to expand their production capacity. Fixed investments are growing very slowly, and real wage rates have been declining for many months, signaling weak demand for labor.

Hence, a defensive approach to financial markets would come from those who believe that growth will be relatively modest (around 3 percent or lower); that supply bottlenecks will be significant because production capacity fails to keep up with demand; and that current tensions in the labor market will reverberate throughout the economy. If this attitude prevails, major sell-offs are around the corner. The Biden administration will then ask the Fed to do what it takes to keep the economy growing while paying lip service to the rhetoric of monetary discipline. The outcome would be stagflation and a stock market crash.

The buy-the-dip narrative is also focused on growth, seeing drops in the stock exchange as having little to do with interest rates. Proponents of this view believe that the U.S. and global growth prospects are satisfactory (at 4 percent or higher for both aggregates in 2022) and realize that the bond market does not present attractive alternatives.

This seems a better description of reality, especially if the Fed’s caution is confirmed. Inflation will stoke a lot of debate, but won’t make much of a difference. According to this narrative, the Fed will refrain from raising interest rates long enough to bring about positive interest rates in real terms. This explains why investors continue (and will continue) to buy equity, especially after the occasional bad news item triggers some taking of profits, as happened in January. If inflation drops – and it will drop, at least a few fractions of a point – investors will anticipate a generous response by the Federal Reserve. Stocks will benefit accordingly.

The U.S. economy is not heading toward a bright future. During the Covid-19 crisis, nothing was done to ensure a more satisfactory, productive track: regulatory and tax pressures remain heavy, and free trade principles do not seem to be President Joe Biden’s priority.

Even if monetary policy becomes less generous than in the past, it will take years before the consequences of monetary manipulation are absorbed and public debt falls back to sustainable levels. Moreover, many companies are overvalued because investors have been looking for equity, especially in the high-tech and clean-energy industries. A large number of such companies are vulnerable and will crash if credit conditions tighten or investors become a little more careful. Portfolios will feel the pain.

Still, the buy-the-dip investors are prevailing, and are right to view the announcements of “tight monetary policy” as not altogether serious. The Titanic has indeed entered choppy waters, but if the current geopolitical situation (with Ukraine and Taiwan) does not deteriorate, it will not meet its iceberg in 2022; the ship is simply slowing down. If the slowdown is moderate and the passengers enjoy the show, the party will go on, without fireworks, for several quarters.