American financial markets and the specter of inflation

The policies of easy money, unlimited public debt and indiscriminate subsidies make fertile ground for inflation. Are the rising interest rates and jittery financial markets signaling that the U.S. and several other Western economies are approaching the end of the long free ride?

In a nutshell

- Financial markets still present a business-as-usual image

- However, interest rates have become a time bomb

- Looking forward, three scenarios emerge

During the past few weeks, the broad economic context has been characterized by three phenomena. The first is that long-term interest rates on American bonds have been rising.

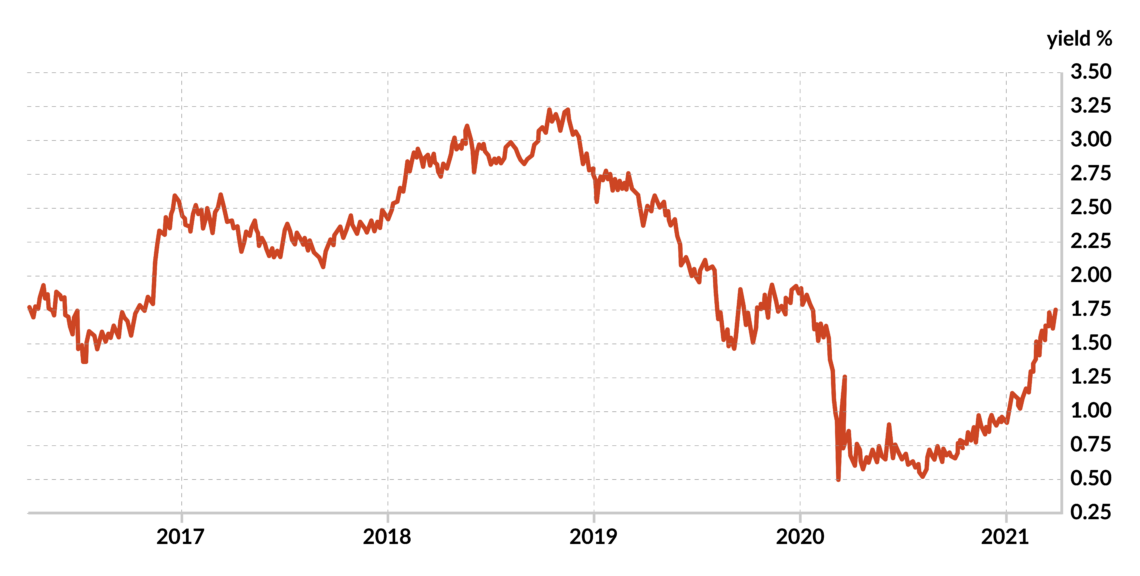

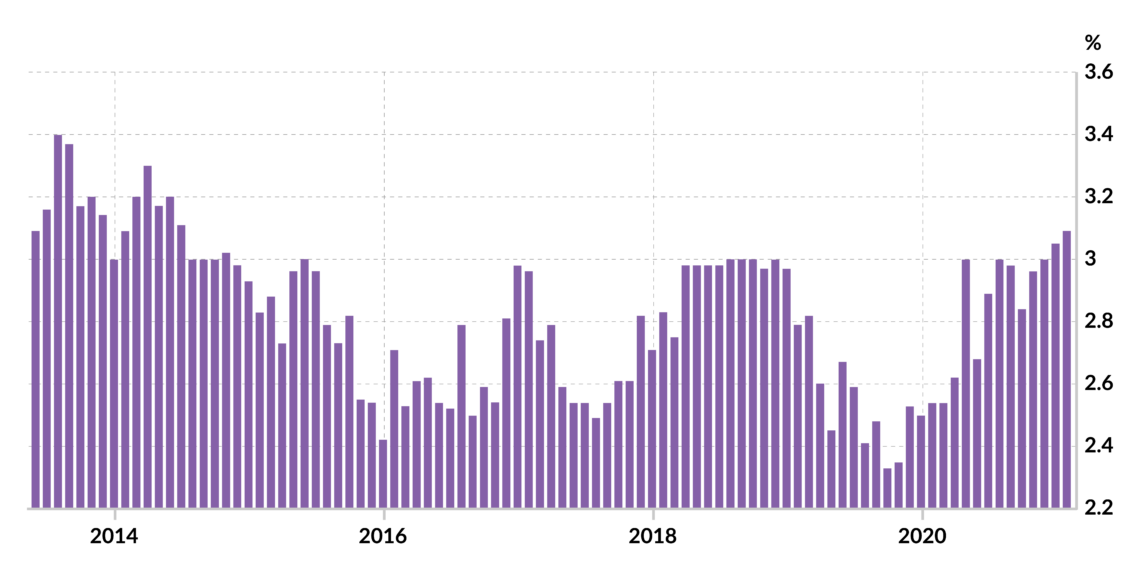

The rate of interest on 10-year Treasuries was at about 0.5 percent in August 2020, reached 0.9 percent in early January 2021 and, as of the end of March, is approaching a new 14-month high of 1.8 percent. The speed of the rise was unexpected and came with accelerating inflation – the second phenomenon – the rate of which rose from 1.2 percent (October-November 2020) to 1.7 percent (February 2021). While this rise may not be dramatic, its speed took observers by surprise and created tensions within the economic community.

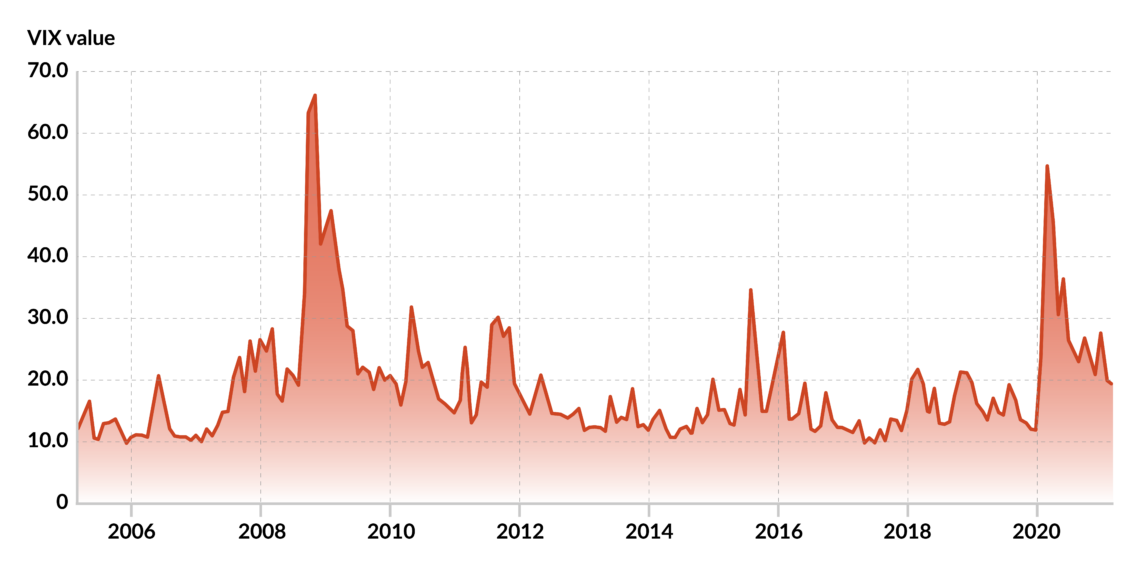

Wall Street has not paid much attention so far. For example, the Dow Jones Volatility Index (VIX) – a measure of the fear felt by financial investors – in mid-March 2021 was significantly lower than a year earlier. Nonetheless, the data on volatility may be misleading in this period, as we shall see shortly.

Facts & figures

The third issue regards how policymakers will move next. Although central bankers have tried to give the impression that everything is under control, investors have started doubting whether authorities are still considering what measures they could implement if a crisis occurs before their terms in office expire.

Overextended free ride

This report makes two general points in this vein and investigates what scenarios could materialize if things go south sooner than anticipated and the authorities are caught wrong-footed. The first general comment regards the nature and consequences of the overlapping policies pursued so far on both sides of the Atlantic. Those policies boil down to easy money, virtually unlimited public indebtedness, more or less indiscriminate subsidies and guarantees to selected interest groups.

With the onset of the Covid crisis, people resorted to saving, which tamed consumer price inflation.

Regrettably, money printing and debt do not create wealth and, therefore, these policies cannot drive an economy out of stagnation or remedy significant drops in production. Instead, they produce fertile ground for inflation and income redistribution (when the debt is spent and then perhaps paid back) or for more inflation (if the debt is monetized, i.e., bought by the central bankers). Indeed, some have the impression that the United States and several other Western economies are nearing the end of an overextended free ride – profligacy with neither reimbursements nor inflation. When the ride is over, they will have to confront the consequences of more than a decade of doing “whatever it takes.”

With the onset of the Covid crisis, people resorted to saving, which tamed consumer price inflation and helped extend the length of the consequence-free profligacy. This explains why inflation showed in financial markets and real estate rather than in consumer prices. Yet, when the Covid restrictions are lifted, fears subside and the savings rate drops, the stock market will stabilize and possibly freeze, while the goods market will heat up. This scenario is where America may be heading at this very moment, while Europe lags.

Faux calm

The second point regards the apparent calm characterizing financial markets. When news about rising interest rates was released, the markets did move, but the movements usually only lasted a few days. The long-term trend dominates, keeping volatility low. Rather than signaling tranquility, however, this behavior indicates that investors still have a limited range of reasonable options and are hesitant to overhaul their portfolios.

Facts & figures

U.S. interest rates are rising, but they are still very low, especially if one believes inflation is around the corner. Prices for bonds drop as interest rates rise, so why buy a 10-year Treasury now? And why bother to buy a one-year bill that yields a miserable 0.06 percent, unless one wants to park liquidity? The upshot is that stocks remain the only choice for many. All this explains why financial markets still present a business-as-usual image. Can this quiet picture change? The answer is a matter of tipping points and timing.

Tick, tick, tick

Interest rates have become a time bomb. The length of the fuse is unknown. Investors acknowledge that many stocks are overpriced, that Wall Street is full of bubbles, and that portfolios are imbalanced. Nonetheless, the returns on buying bonds must rise much higher, and inflationary expectations fade away before a sharp change in investment strategies occurs.

In particular, three scenarios may occur. One involves higher interest rates driven up by stable inflationary expectations. This is the most likely outlook, especially if the effects of generous monetary policy are compounded by fiscal profligacy. The crucial variable is not the actual rate of inflation but expectations about future rates.

A banking crisis would follow, and Wall Street would experience an epic crash.

Suppose that today’s expectations for inflation in 2022 stabilize at about 3 percent, which is the current level and would also reflect what the Federal Reserve seems to consider appropriate. Will this be enough to rock the boat? Our answer is no, for two reasons. Investors will not panic as long as real interest rates remain close to zero, just as they are today. High nominal interest rates could be problematic, but only beyond a tipping point, as we will soon explain.

On the other hand, a radically different scenario could materialize if inflation beats expectations, public debt expands rapidly and the Fed prevents interest rates from rising to spare the government exceedingly heavy debt servicing. Individuals and investment funds would understandably stay away from interest-bearing securities, the outcome would not change significantly: stock prices would rise, and so would those of real estate, precious metals and digital currencies.

The worst possibility

Yet another possibility might emerge; it is not remote and much less reassuring. It would occur if the Fed fears that inflation is out of control, declines to finance the public budget deficit and stops manipulating the money market. In other words, it stops printing money and lets interest rates rise.

Under such circumstances, interest rates would soar. The cost of debt servicing would make the U.S. public debt unsustainable, and many heavily indebted companies would be unable to find affordable financial resources. Those not acquired by more stable firms would have to go broke. A banking crisis would follow, and Wall Street would experience an epic crash, which would also affect relatively healthy companies.

If it materialized, this financial crisis would be much worse than the one the world experienced in 2008/2009 since it would include creditors (banks) and debtors – companies and the government. In contrast with the Great Recession, derivatives, overpriced real estate collateral and liquidity problems would not be the issue for banks. This time, they would suffer as indebted companies go bankrupt and never pay back their loans. At the same time, outstanding long-term loans would yield inadequate returns, and the value of the long-term Treasury bills listed among the banks’ assets would drop significantly.

Of course, high inflation would reduce the real burden of public indebtedness and could be part of an international strategy to solve the public-debt problem. However, the price/cost relationship in the real economy would be exorbitant and create dangerous tensions within American society.

To summarize, the critical variable to consider looking ahead is inflation, rather than the occasional jitters generated by the news about interest rates. These are important, of course. Yet, they follow inflation and the willingness shown by the Fed to finance the government. The interaction and timing between these two variables will tell us when we have to brace for stormy weather.