Turkey maneuvers to become a regional energy baron

Turkey has become a major player in delivering energy supplies from the Caucasus to Europe. As Russia’s grip on the region weakens, it could lead to serious security concerns, with Ankara increasingly willing to defend its interests militarily.

In a nutshell

- The Turkish-Azeri axis is getting stronger

- Energy supplies from Turkey play a major role in the Caucasus

- Russia is no longer the sole hegemon in the region

The outcome of the six-week Nagorno-Karabakh war last year was a major triumph for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. By providing decisive political and military support for Azerbaijan, he altered the geopolitics of the South Caucasus. The changes will have profound implications, both for Turkey’s role as a regional power and for the future of relations between Ankara and Moscow.

Although the most immediate loser in the war was Armenia, whose troops came close to a complete rout from Azeri territory, in the longer-term strategic perspective, Russia has real cause for concern. The Kremlin can take some credit for having brokered a cease-fire agreement. And by having peacekeepers on the ground, Moscow will also play an important role going forward. But the regional dynamics have now been transformed.

In 1994, when the first cease-fire was agreed upon in the war between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Russia was the unquestioned regional hegemon. When the Minsk group was formed to find a peace settlement, it was natural that Russia would take the lead. Over the coming quarter-century, Moscow would manage to keep the conflict frozen, by playing both sides. Turkey was not even consulted.

In regional energy politics, Turkey now stands to emerge as the new hegemon.

By moving so decisively to support the Azeri offensive, President Erdogan achieved two important goals. First, he has shown that Russia was too weak to keep the conflict frozen. Second, he has ensured that when the time comes to find a resolution, he will have a seat at the table. Moreover, the outcome has deepened the long-standing goodwill between Ankara and Baku. This will be felt, above all, in regional energy politics, where Turkey now stands to emerge as the new hegemon.

Pipeline politics

Azerbaijan is a key link in the chain that runs from the immense energy resources in the Caspian Basin to the crucial markets of Europe. It was a watershed in 1994 when the regime in Baku concluded a deal with foreign energy giants to begin exploiting its offshore oil and gas reserves. With the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli and Shah Deniz oil and gas fields in operation, the stage was set for Azerbaijan to become an influential petrostate. Combined with the even more substantial energy resources in Central Asia, the race was on over who would control the flow to Europe.

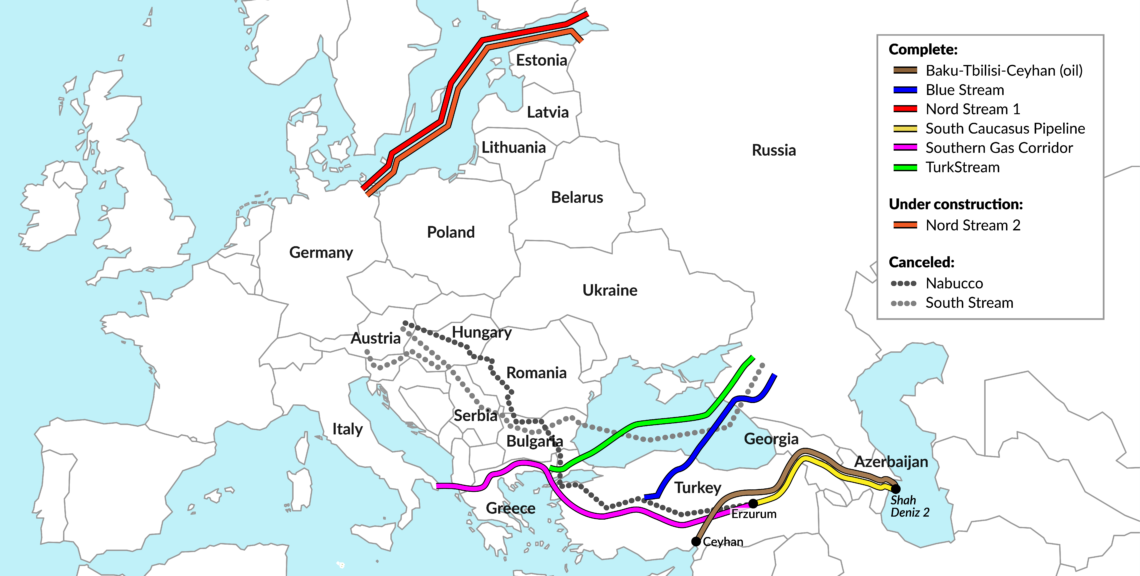

The first developments served Russia with major setbacks. Having long viewed both Central Asia and the South Caucasus as its spheres of influence, the Kremlin had honed the use of energy exports as a tool for foreign and security policy. In 2006, the commissioning of two new pipelines from Azerbaijan to Turkey dealt a blow to this strategy.

Operated by a BP-led consortium, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline and the South Caucasus Pipeline for natural gas combined to open the first route for energy from the Caspian Basin to Europe without passing through Russia.

Keen on diversifying its energy sources away from Russia, the European Union launched a project to construct a gas pipeline from Azerbaijan via Turkey into Europe, ending in Austria. Named Nabucco, after the Verdi opera, that project collapsed in 2013 when Azerbaijan opted out.

Russia launched an even more ambitious project to pipe its gas under the Black Sea to Bulgaria and on through Serbia, Hungary and Slovenia to Italy and Austria. Named South Stream, it was met by severe EU regulatory hurdles and collapsed in December 2014.

Turkey’s rise

Much as Ankara had not been accepted as a partner in the Minsk process, in the energy competition Turkey’s own energy supplies had little relevance and it was rather seen as a market for Russian energy. In 2002, Russia sought to lock in that market, by launching the Blue Stream pipeline to ship gas across the Black Sea, from the Beregovaya compressor station in Krasnodar Krai to the Durusu terminal near Samsun on the Turkish coast and onward to Ankara.

In 2016, the defunct South Stream project was succeeded by TurkStream, again designed to ship Russian gas across the Black Sea, but now to a point in the European part of Turkey and onward to southeast Europe. When gas first started flowing, in January 2020, the relative geopolitical positions of Moscow and Ankara had fundamentally changed.

The Kremlin had honed the use of energy exports as a tool for foreign policy.

The $40 billion Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) made the biggest impact. Officially inaugurated in Baku in May 2018, it is a 3,500 km-long transport artery for natural gas that involves six countries – from Azerbaijan via Georgia and Turkey, to Greece, Albania and Italy. The first two links in this mammoth project are the $28 billion BP-operated Shah Deniz 2 gas field, which came online in June 2018, and the South Caucasus Pipeline Extension, which pumps the added volumes to Turkey via Georgia. The central part is the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), which pumps gas across Turkey to Bulgaria. Launched at the end of 2019, TANAP cements the energy link between Turkey and Azerbaijan.

The final portion of the SGC is the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which began commercial operations in November 2020. Designed to pump gas from TANAP via Greece to Albania and across the Adriatic Sea into the south of Italy, it will open large European markets for gas from Shah Deniz 2. Gas from Azerbaijan is expected to satisfy about 30 percent of demand in Bulgaria, 20 percent in Greece and 12 percent in Italy.

Recalibrated relationship

These developments rebalance the relationship between Moscow and Ankara. Given the increased military posture of Russia in the Black Sea region, Turkey has reason to tread lightly. The two countries have opposite agendas not only in Syria, but also in Libya and now in the South Caucasus.

There have also been confrontations involving the death of Russian servicemembers. In 2015, a Turkish F-16 fighter jet shot down a Russian Su-24 attack aircraft that had strayed very briefly into Turkish airspace, from a mission inside Syria. The pilot was killed. During the recent war in Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia also suffered the loss of an Mi-24 helicopter gunship, shot down by Azeri forces while it was escorting Russian ground troops inside Armenia. Two crew members were killed. Although Russia did not retaliate on either occasion, there is obvious danger involved.

President Erdogan’s style has become increasingly assertive because Turkey’s energy supplies have become self-standing, thus greatly reducing its dependence on Russian energy. TANAP has substantially increased deliveries of gas from Azerbaijan. In May 2020, it became Turkey’s top energy supplier, outstripping both Russia and Iran. The displacement of imports from Gazprom is especially striking. Having accounted for 52 percent of Turkey’s total gas imports in 2017, by 2019 its share had fallen to 33 percent. In the first quarter of 2020, it dropped below 10 percent.

Facts & figures

One consequence is that the Blue Stream pipeline, which was closed for maintenance in May, has not been reopened. In the words of a Russian source, “There is no point in using both pipelines if only one [TurkStream] is more than enough.” As contracts for gas from Russia expire in the coming years, Ankara will gain greater leverage.

Another reason for the sharp drop in Russian gas imports is that Turkish imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) more than doubled between 2013 and 2019, from 6.1 billion cubic meters (bcm) to 12.7 bcm. During the first half of 2020, imports of pipeline gas fell by 22.8 percent while imports of LNG increased by 44.8 percent. For the year as a whole, LNG is expected to account for 35 percent of gas imports. While the main sources are Algeria, Nigeria and Qatar, Gazprom is probably more worried about LNG imports from the United States tripling in the first quarter of 2020.

Turkey’s energy supplies are also becoming increasingly self-sufficient by finding energy resources of its own. The most notable event was the recent discovery of a gas field off the Turkish coast in the Black Sea. Called the Sakarya field, initial estimates said it could hold 320 bcm. During a press conference in late October, held on the Fatih drilling vessel, President Erdogan announced that added exploration had caused the estimate to rise to 405 bcm. Calling the find a “morale booster,” he went on to say that the find would “significantly reduce Turkey’s reliance on foreign resources.” With a second drillship en route, the estimate may rise even further.

Turkey has also sparked a diplomatic row with the European Union by resuming natural gas exploration in contested waters off Cyprus. In the face of protests from both Greece and Cyprus, and of French naval exercises in the area, President Erdogan vowed that Turkey was “determined to defend its interests” in the Mediterranean Sea.

Security factor

Although Gazprom has reason to be concerned about the loss of revenue, in the larger energy relations between Russia and Europe, the Southern Gas Corridor is important, but not the biggest difficulty. The current capacity of TANAP is up to 16 bcm per year, of which 10 bcm will go to Europe and 6 bcm to the Turkish market. The ambition is that by 2026 it will have reached a capacity of 31 bcm. With minor modifications, TAP could double its capacity to 20 bcm. While this will be important for southern Europe, it is still only a fraction of Russian gas imports to Europe.

Russia will have to contend with an increasingly aggressive Turkish military posture in its backyard.

Gazprom has been successful in winning backing from Berlin for two pipelines – Nord Stream 1 and 2 – that pump gas directly from Russia to Germany via the Baltic. With a joint capacity of 110 bcm, Gazprom can shut down all transit via Ukraine and still retain a firm grip on the European market.

Outlook

The main reason for Russia to be concerned about the enhanced role of the axis between Azerbaijan and Turkey remains security in the South Caucasus, where Ankara is developing a significant stake in ensuring that critical infrastructure will not be targeted.

During the 2008 war in Georgia, all pipelines transiting the country were shut down. During the recent war in Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkey was particularly worried about the Tovuz region in northern Azerbaijan, where the crucial pipelines run. As the energy partnership between Baku and Ankara deepens, so will the military cooperation.

The outlook for the Kremlin goes beyond being displaced as the regional energy hegemon. It will also have to contend with an increasingly aggressive Turkish military posture in its backyard. And if push comes to shove, President Erdogan has already shown that he is not the one to blink first.