Erdogan weakened or invigorated?

Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s reelection has shed light on long-standing Western misconceptions about Turkey’s political landscape.

In a nutshell

- President Erdogan’s reelection confounded Western predictions

- His victory has consolidated his stronghold on Turkish politics

- The economy and foreign policy will remain top priorities

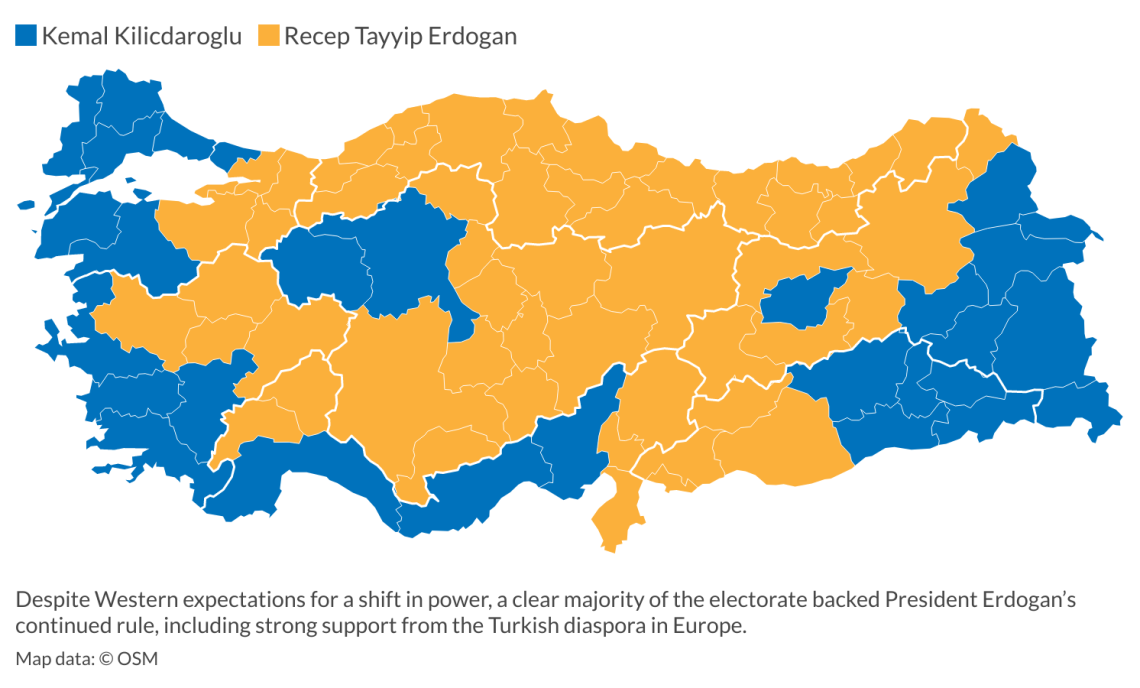

Despite predictions to the contrary by polls, the opposition and most Western media, Turkey’s incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, after 20 years in power, was reelected with a 52 percent absolute majority with a turnout of around 85 percent.

Many had hoped for a radical change to a supposedly more democratic and liberal governance. These expectations were shared and amplified by vocal opponents to the Erdogan administration, often prominent voices of the Turkish diaspora in Europe. But these predictions were largely based on wishful thinking.

It is true that Erdogan-friendly media dominate the public space in Turkey. The advantage of being able to use the state apparatus as well as to bend “rule of law” principles made the election campaigning unfairly lopsided. Yet it is hard to deny the validity of the final result, given the tightly monitored elections and the impressive voter turnout, which is regularly much higher in Turkey than in most Western democracies.

The West taking sides

The American and European public, and even some governments, had displayed a clear preference for opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu and his six-party coalition. They came together with one aim – to unseat President Erdogan, Europe’s longest-ruling leader, in power since 2002.

It is puzzling that even after his victory, many in the West are finding it hard to come to terms with their frustrated expectations and insist on viewing the result as the “beginning of the end of Erdogan.” They have also come up with arguments to compare him to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and even Russian President Vladimir Putin to justify their unshakable views and doomsday prophecies of a lifelong dictatorship. It is mostly overlooked that the West’s “choice against Erdogan” may have motivated Turkish voters to cast their vote in the incumbent’s favor.

While there is an almost global consensus that citizens living abroad should be able to cast their votes for their home countries’ elections, European commentators have called into question this very principle when it comes to Turks living in EU countries. The roughly 5 million Turks or people of Turkish descent in the EU were strongly in favor of Mr. Erdogan (up to 75 percent in Austria).

Facts & figures

Such Western attitudes may reflect regret that Turkey is drifting away from European values, and fears that Western interests are ultimately being jeopardized. Europeans are still coming to terms with their concerns over the rise of an incredibly fast-growing, strategically located, non-Christian “illiberal” neighbor with a long history as a major power. Subconscious unease with this growing size and conservative “otherness” in relation to the West is palpable when the latter judges Turkey – or Türkiye, as the country now wishes to be called.

What comes next for Turkey under Erdogan

After President Erdogan’s reelection and the total overhaul of his cabinet on June 3, there will be policy shifts, especially surrounding the economy and the fight to tame inflation and stabilize exchange rates. Mehmet Simsek, highly rated both in the West and at home, is back as minister of economy and finance and will likely make sound policy moves. He and Vice President Cevdet Yilmaz, both prominent Kurdish politicians from central Anatolia, were already cornerstones of a successful cabinet team 10 years ago.

In foreign affairs, we can expect continued stability through pragmatic adjustments from the experienced new foreign minister, political heavyweight Hakan Fidan. The past decades have seen a steady flow of wild ups and downs in Turkey’s policies: the downing of Russian military aircraft followed by excuses and reconciliation, frozen relations with Israel followed by step-by-step reconciliation, and similar developments with Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

Turkey’s foreign policy will necessarily continue to be a tightrope balancing act between difficult neighbors and superpowers, sometimes requiring quick adaptations. Geography matters. The country lies between several power centers and crisis zones. Ankara will therefore continue to tread cautiously and try to steer a neutral course between Russia and Ukraine, promoting pragmatic solutions like the July 2022 UN co-sponsored agreement to resume grain and fertilizer exports through the Bosporus.

Government policy priorities will stay the same: protect the borders (keeping guerillas of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party at bay), maintain peace through a prosperous economy, tame inflation and keep energy supplies affordable. With major natural gas finds in the Turkish Black Sea, the temptation to pursue an expansive Eastern Mediterranean policy has eased. This will help reestablish sustainable and courteous, if not cordial, relations with neighbors in an arc that spans from Greece to Armenia.

All scenarios for Turkey remain strongly dependent on the United States and other foreign input. With the war raging in next-door Ukraine and inflation running high at home, developments outside Turkey could have a disproportionate bearing.

Is polarization just a catchword?

In the run-up to the elections, analysts had been pointing at a dramatic polarization of Turkish society. But looking more closely, we can find arguments that speak also in favor of increased cohesion.

Over the last 20 years, a redistribution of influence and wealth has diminished Istanbul’s relative weight and terminated the military’s privileges. An impressive modernization of road, rail and air links, connecting some 784,000 square kilometers of territory, has made the country more integrated and hence less polarized, at least economically.

With a record of unexpected reconciliation moves in foreign policy, we can anticipate similar initiatives on the domestic scene once the 2024 municipal elections have taken place. But first, expect President Erdogan to try hard to reconquer his hometown of Istanbul (and Ankara, if possible), lost to Mr. Kilicdaroglu’s Republican People’s Party in 2019.

More by Klaus Wölfer:

As Turkey begins its second century, uncertainty looms

Serbia sees itself as heir to Yugoslavia’s nonaligned tradition

Scenarios

After the 2024 local elections, four years of clear-cut political dominance – controlling both the presidency and an absolute parliamentary majority, and no elections until 2028 – would theoretically lie ahead. During these four years, the president will have time to prepare for his succession and retirement, making sure that he and his family members will be held in esteem and be spared the sort of legal trouble experienced by Presidents Lula, Trump, Sarkozy, and so forth. Before then, Mr. Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) might well split, dissolve or morph into something else, potentially lessening the contrast with a unified opposition bloc.

During the campaign, Mr. Kilicdaroglu took a last-minute, populist swing toward a harsh expulsion policy against millions of mostly Syrian refugees – a decision that may create a lasting burden for the opposition. Between this and the prominent role of Kurds in the new government, there will be extra pressure on the left-wing, pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), and further strains on the six-party opposition alliance.

There is indeed enormous popular support for a visible and substantial repatriation of Syrians. The new government will accelerate the construction of homes for returnees in northern Syria and likely seek a settlement with President Bashar al-Assad.

When it comes to relations with Turkey, European countries will focus on security and NATO issues, as well as the 5 million first or second-generation Turks living in Europe. They will also seek balanced trade relations.

In this context, close interaction is indispensable and clearly in the cards – but with the usual fits of EU-Turkey controversy. Both sides stand to gain from good relations and both sides need each other, almost desperately.

Brussels must have realized what the implementation of Mr. Kilicdaroglu’s plan to expel millions of Syrian refugees would have meant for the EU.

Most European nations are entangled in a costly and dangerous war in Ukraine, which is cutting an expanding “Western” Europe off from its natural continental hinterland and from the fast, cheap and ecological land routes to China and Central Asia. Hence, Europe will need a stable and reliable Turkey.

President Erdogan’s swearing-in ceremony was attended by NATO representatives as well as leaders and high-ranking dignitaries from all over the continent. Clearly, the Turkish leader continues to hold sway over vital issues in the region.