The Trump maritime strategy

The U.S. Navy is again on the leading edge of American foreign policy. Freedom of Navigation missions and bold forward deployments of carrier task groups are just part of a new policy. For the Trump maritime strategy to work, it must be sustained by effective communications and diplomacy and an accelerated naval construction program.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. has stepped up freedom-of-navigation and carrier operations in the Pacific

- Naval forces have gained new prominence as tools of diplomacy and deterrence

- Without political support and fleet expansion, this new maritime strategy may not work

One of the hallmarks of President Donald Trump’s administration has been a much bolder use of United States naval forces in troubled international waters. The signature moment was the decision to deploy three aircraft carrier strike groups to the western Pacific in 2017, as the nuclear crisis with North Korea was heating up. In contrast with his immediate predecessors, President Trump has not hesitated to put the U.S. Navy at the leading edge of foreign policy, as an active strategic deterrent against rival powers – especially China and Russia.

The result has been an increased tempo of naval operations, closer cooperation with U.S. allies and friends, and less collaboration with potential adversaries. This new approach – which appears comprehensive and consistent enough to have the makings of a maritime strategy – has if anything continued to intensify since Defense Secretary James Mattis resigned in December 2018.

Faster pace

One indicator has been the frequency of “freedom of navigation” operations (FONOPs), which have been routinely conducted by the U.S. Navy since the late 1970s to challenge “excessive maritime claims” by rival powers.

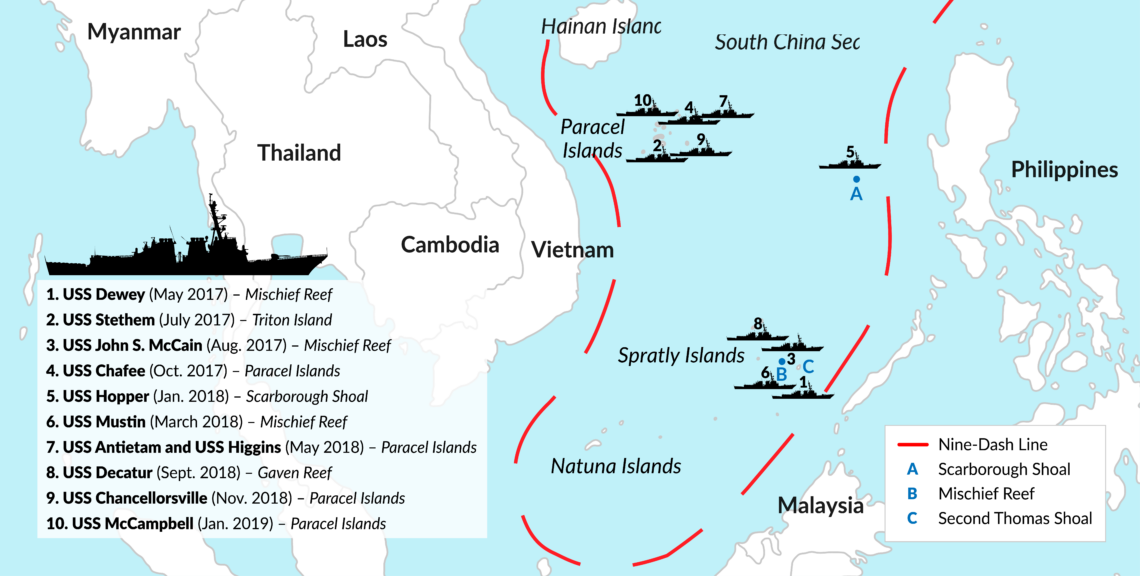

Just a week after acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan took over at the Pentagon, on January 7, 2019, the guided-missile destroyer USS McCampbell passed within 12 nautical miles of the Chinese-claimed Paracel Islands in the South China Sea. This followed up on a visit by the guided-missile cruiser USS Chancellorsville in November 2018, making clear that U.S. naval forces would continue their two-year pattern of high-frequency FONOPs in these disputed waters.

The same day, halfway across the world, the dock landing ship USS Fort McHenry paid a courtesy call to the Romanian port of Constanta. It was the first visit by a U.S. warship to the Black Sea since Russia seized three Ukrainian vessels in the Kerch Strait in late November 2018. Less than two weeks later, on January 19, the guided-missile destroyer USS Donald Cook transited the Bosporus Strait, driving home the message to Moscow.

Another hot spot visited by U.S warships in January was the Taiwan Strait. Returning from the South China Sea, the USS McCampbell, sailed through this sensitive maritime choke point with the oiler USNS Walter S. Diehl. It was the third such passage by U.S. vessels in the past four months.

Exposing Beijing

In all these cases, the Trump administration underscored its commitment to use the U.S. Navy to signal American resolve in confronting bad behavior by China and Russia. This new Trump maritime strategy offers distinct advantages at a time when Americans have grown weary of overseas troop deployments. It would mark a break from the three-decade practice – ever since the First Gulf War in 1991 – of using ground forces first to deal with foreign threats.

Partly by design, the aspect of this strategy that has attracted the most media coverage has been the FONOPs conducted by U.S. naval and air forces around the globe. The most notable example has been the South China Sea, where the U.S. Pacific Fleet is reported to have conducted at least 10 such missions during the first 24 months of Donald Trump’s presidency. That is a significant increase from the Obama administration, which staged six FONOPs in the same area between 2013 and 2016.

Facts & figures

Freedom of Navigation Operations in the South China Sea

(May 2017-January 2019)

While academic analysts and the media have focused on mission frequency, the true impact of these operations has been in making plain China’s strategic intentions in the South China Sea. The Trump administration’s more assertive FON program has exposed Beijing’s excessive and confusing territorial claims, while highlighting its flawed interpretation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Without such prodding, it would be much easier for China to intimidate its neighbors through a gradual military buildup and “salami slicing” tactics aimed at gradually achieving control over the entire South China Sea. Beijing’s strategic goal is to confirm its sovereignty over these waters according to the so-called “nine-dash line,” ruled unlawful by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in July 2016.

The FON program’s critics have rightly noted that these operations alone have been insufficient to halt or even slow Beijing’s military buildup in the region. That is why it is important to consider other naval operations that do not come under the FONOPs rubric, particularly those including the core of U.S. naval power – carrier strike groups.

Clearest message

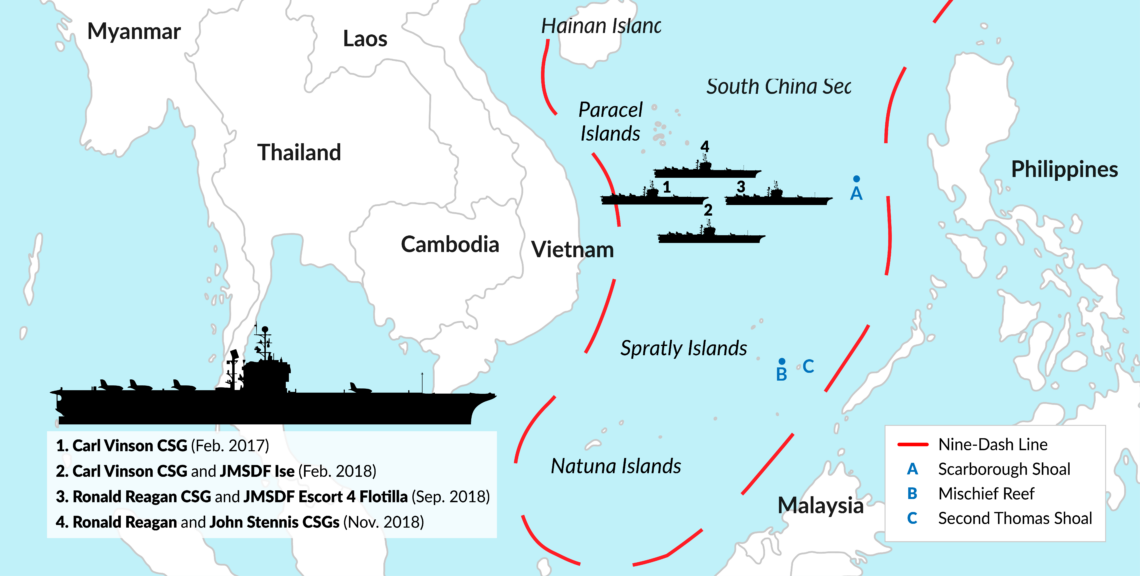

On this front, the most visible manifestation of the Trump maritime strategy has been the increased number of aircraft carrier operations in the South China Sea. These have involved both single and multi-carrier groups, as well as task forces operated by U.S. allies.

To be fair to the Obama administration, high-profile carrier operations in the South China Sea were initiated in March 2016, when the USS John C. Stennis, a 103,000-ton supercarrier, led its Carrier Strike Group (CSG) into the area. Three months later, in June and July of 2016, the Stennis returned for joint exercises with another carrier group led by the USS Ronald Reagan. These operations provided a foundation on which the Trump administration built over the next two years.

The U.S. has not conducted carrier operations in the South China Sea at this tempo for half a century.

Within a month of President Trump’s inauguration, the administration ordered the Carl Vinson carrier strike group into the South China Sea for flight operations (February 2017). A year later, the Vinson returned for joint exercises with the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) helicopter carrier Ise in February 2018. This multinational mission sent an especially strong message to the Chinese authorities, who had characterized dual-carrier operations in the South China Sea as crossing an important “red line” for Beijing.

Undeterred by such rhetoric, the Trump administration followed up with another combined U.S.-Japan naval operation in September 2018, this time composed of the Ronald Reagan carrier strike group together with the JMSDF’s Escort Flotilla 4 battle group. A month later, the Reagan was back in the South China Sea, operating alongside a second carrier strike group led by the John C. Stennis.

Having served for most of my naval career in the Pacific Fleet, I can attest that the U.S. has not conducted carrier operations in the South China Sea at this tempo for half a century, since the Vietnam War. As a message to China, it is the clearest statement imaginable of American naval power, and sufficient by itself to validate Beijing’s fears of a U.S. strategic response to Chinese expansion.

Carrier diplomacy

Deployments elsewhere confirm a shift in U.S. strength toward the Western Pacific. As previously mentioned, the decision in October 2017 to send the USS Nimitz into the 7th Fleet area of operations brought American carrier strength in the region to three. These supercarriers, operating with their escort ships and embarked air wings, cruised off the coast of Korea for four days in November 2017. While the immediate target of this unprecedented concentration was Kim Jong-un, there was no mistaking that China was also an intended recipient of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign to get the North Korean leader to abandon his nuclear weapons.

Facts & figures

Carrier operations in South China Sea

(February 2017-November 2018)

If this were not enough proof, the historic port call by the Vinson carrier strike group to Danang, Vietnam, in March 2018 certainly added to Beijing’s concerns. The visit was widely reported in the region and marked another attempt to use the U.S. Navy for diplomatic leverage. The symbolism of the first visit by a U.S. carrier to Vietnam since the 1970s could not be missed, and the friendly gesture came just as tensions between Hanoi and Beijing over oil drilling rights in the South China Sea were heating up.

Finally, it is worth noting that the Trump administration’s new maritime strategy is not limited to the Pacific and China. There have been a number of similar examples recently when the U.S. Navy has been used to signal American resolve and commitment to Russia. In October 2018, the USS Harry S. Truman operated off the coast of Norway in Exercise Trident Juncture, the first time an American carrier strike group had ventured north of the Arctic Circle since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Earlier that year, the Truman’s air wing had participated in the Baltic Operations (BALTOPS) 2018 exercise, the first appearance of U.S. carrier aircraft at these annual maneuvers since 1972.

Toward implementation

These naval developments are part of a larger sea change in American policy. Under the new administration, there has been a frank recognition of the threat posed by China to U.S. national security, especially through its ability to project sea power. This “cultural” change is broad-based, encompassing economic and trade relations, technology and intellectual property, and is being driven from the top – from President Trump. Yet a number of policy areas still need attention.

If naval power is to become an effective tool of American foreign policy, political support must be mobilized.

Strategic communications: Simply acknowledging that the U.S. and China have entered a new period of competition does not amount to a strategy, no matter how resolute our assertion of core interests and principles. If naval power is to become an effective tool of American foreign policy, political support must be mobilized both at home and among U.S. allies and friends. This requires a coherent strategic communications plan, dovetailed with the National Security and National Defense Strategy documents already published by the White House. More aggressive showcasing of maneuvers displaying the capabilities of U.S. and allied naval forces, along the lines of Exercise Trident Juncture in Norway, would also help in this regard.

International law: While the U.S. has not ratified UNCLOS, that should not inhibit the administration from incorporating the convention’s principles in its maritime strategy. Doing so will highlight where China and Russia ignore or violate international norms in the maritime commons. China’s illegal actions in the South China Sea and the degree to which the international community tolerates them will have serious consequences in other sensitive areas, including Antarctica, the Northwest Passage, and even in outer space.

Allies and partners: Washington has started to take a more active approach to military cooperation. In the Pacific, for the first time, it decided in 2018 to disinvite China from the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercises – the largest multinational naval maneuvers in the world. The next step might be along lines suggested by Tuan Pham and Grant Newsham, who have advocated a RIMPAC-style naval exercise in the South China Sea to rally ASEAN member states against Chinese claims.

Additionally, under the auspices of the Trump Maritime Strategy, the U.S. could enlist members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (or “Quad,” consisting of Australia, India, Japan and the U.S.) in a naval exercise within the First or Second Island Chains. That would serve to remind Beijing that its provocative actions in the maritime domain will not go unchallenged.

Assets: With the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) on track to field 500 major surface combatants and submarines by 2030, the U.S will not be able to effectively deter Chinese expansionism without increasing the size and capabilities of its fleet. The administration’s initial plan to build a 350-ship navy may not be enough to match China’s buildup. The U.S. will also have to accelerate the development of a new generation of supersonic, long-range anti-ship cruise missiles. Today, China can “out-stick” the U.S. Navy from a variety of surface and undersea platforms. Unless this strategic trend is reversed, the U.S. risks being perceived as a paper tiger in Asia.

Scenarios

Scenario 1: active strategy

The first and most challenging scenario would see the Trump administration formally announce its maritime strategy. This would expand the existing legal warfare effort (mainly through the FON program) through robust naval operations within the First Island Chain, which runs from Japan through Taiwan, the Philippines and Borneo. In support, exercises and patrols with allies like Australia, France, India, Japan and the United Kingdom, along with other partners among the ASEAN countries, would be increased.

This scenario would involve more forward basing of U.S. naval assets, including the posting of more submarines to the 7th Fleet area of operations (running from the Central Pacific to India and Sri Lanka) and another aircraft carrier to Guam.

In response, one can expect vociferous complaints from Beijing about a U.S. policy of “China containment.” In addition to an information campaign labeling the U.S. and its allies as aggressors, President Xi Jinping would very likely give the Chinese naval and air forces less restrictive rules of engagement that would allow them to approach more closely U.S. and allied units within the First and Second Island Chains (formed by Japan’s Ogasawara Islands and the U.S.-controlled Marianas). This would significantly increase the chances of a military incident, even though it is highly unlikely that the Chinese leadership would authorize direct action against U.S. forces. Quite simply, Mr. Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are not yet prepared for an armed conflict.

However, this “doubling down” scenario is only possible if the Trump administration takes the steps outlined above to build political and diplomatic support, as well as to remedy the growing disparity in forces. This will require working with the House of Representatives, controlled since the midterm elections by the opposition Democrats. Such collaboration should not be taken for granted, given the Balkanized atmosphere now prevailing in Washington.

Scenario 2: passive enforcement

The other plausible scenario flows from domestic political dysfunction in the U.S. If the Democratic-led House of Representatives does not align with the administration’s maritime strategy, they can effectively suffocate it by refusing the funding for a naval construction program. Without the necessary number and types of warships and submarines, the U.S. Navy cannot sustain a more aggressive presence within the First and Second Island Chains.

In that event, it is entirely possible a new administration will abandon the Trump maritime strategy after the 2020 elections. U.S. China policy would revert to the more passive strategy of engagement it has followed for the past 40 years.

This development would be welcomed in Beijing, especially as it would allow Mr. Xi and the CCP to continue their preferred trajectory of a “great rejuvenation” and their plans to make good Chinese territorial claims. The period of highest risk starts in 2020, when China’s ambitious construction program begins to tilt the ratios of naval strength in the PLAN’s favor.