Ukraine moves to liberalize its farmland market

The potential of Ukraine as a major international player in agricultural production was held back for nearly 20 years by a ban on land sales. These bans have been relaxed by parliament, mostly due to pressures from the West. A gradual market liberalization is now planned.

In a nutshell

- Ukraine is rich in fertile farmland

- After independence, the state banned sales of land

- A recent reform aims to liberalize the market to attract private investment

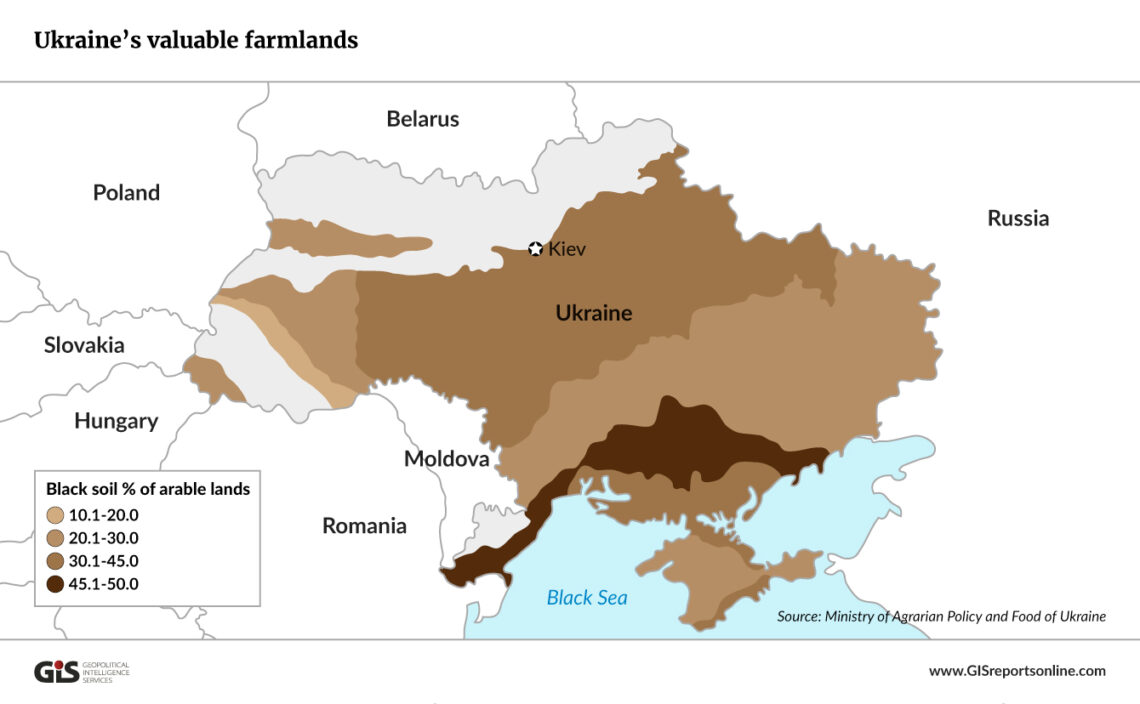

Ukraine, the world’s 44th largest country, is the ninth richest in arable land. Of its 32.5 million hectares, some 13 million hectares of farmland contain a rare treasure – the extremely fertile chernozem (“black soil,” humus-rich grassland soil). The country is Europe’s largest stock of such soils, and its capacity as a farm goods producer and exporter is unquestionable.

However, a quarter of these riches belongs to the state. Since Ukraine’s independence, much of the country’s farmland has been divided into small plots and is being cultivated by about 7 million farmers and part-time farmers who cannot sell their fields. For nearly two decades, a ban on all commercial turnover of land has been in effect.

On March 31, 2020, under significant pressure from the West, Kiev made a critical step toward unlocking the country’s agricultural potential. The Verkhovna Rada, the country’s parliament, gave the final approval to legislation that will allow private land transactions. However, the reform’s implementation will be gradual and much will depend on the vagaries of Ukrainian politics. The country’s overall gains will be determined by how the farm sector will develop.

Facts & figures

Fears and opportunities

Agricultural land has been officially off the market since Ukraine’s independence in 1991. A moratorium on trade was introduced in 2002 and repeatedly extended since then. The policy reflected societal expectations. Studies have consistently shown that about 70 percent of Ukrainians oppose private agricultural property. There is a grave historical trauma behind this sentiment, but also a concern that once the restrictions are lifted, the most valuable land will wind up mostly in the hands of oligarchs and wealthy foreigners.

Ukrainians are keenly aware of their country’s potential in agriculture. For centuries, the region was regarded as “the granary of Europe,” exporting food to the rapidly industrializing nations of the West. However, the land ownership issue is also connected to the Great Famine, caused by the Soviet authorities in 1932-33, in which several million people lost their lives.

Today’s widespread conviction that land is the state’s property is a legacy of that era.

The cold-blooded genocide was Moscow’s reaction to the resistance of Ukrainian peasants against forced collectivization – the integration of individual landholdings and labor into state-owned farms. Today’s widespread conviction that land is, in principle, the state’s property is a legacy of that era. (Tellingly, in regions such as Transcarpathia, Bukovina, Eastern Galicia, or the two provinces of the historic Volhynia that were not part of Soviet Ukraine before World War II, attachment to private property is more pronounced.)

Under these constraints, agricultural producers in Ukraine have operated mainly on land lease contracts, usually for 10 to 15 years. Nonetheless, large holdings leasing hundreds of thousands of hectares already account for most of the agricultural production. Such tenants have had no incentive to invest and care for the soil properly. Simple crops, such as maize and oilseed, dominate production. Also, the problem of pollution and land degradation has reached catastrophic proportions in some areas.

The sector’s overall efficiency is weak. The World Bank assesses the value-added obtained from one hectare of land in Ukraine at only $413. In neighboring Poland, it is $1,142; in Germany $1,507; and $2,444 in France. Despite the holdbacks, agriculture remains one of Ukraine’s breadwinners.

Depending on weather conditions, it has generated from one quarter to a third of the country’s export revenues in recent years. In 2019, this amounted to 44.3 percent of more than $50 billion worth of exports, which helped push Ukraine’s gross domestic product (GDP) to $150.4 billion – up from $130.86 billion in 2018.

Western interest

Since the 2014 Maidan revolution, investors from the West have shown a growing interest in Ukraine’s agricultural potential. Many of those parties have backing from their governments. The richest Ukrainians also supported land marketization schemes – especially oligarchs who hoped to benefit from it. Successive Ukrainian governments sought a way around the roadblock but were unable to find one.

Enter the International Monetary Fund. Commercializing the nation’s land resource has been listed among the IMF’s top recommendations for Ukraine. Other foreign institutions as well had been pointing to land sales as the most obvious way to improve the Ukrainian state’s finances. President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s government gave the idea the final, decisive push after the IMF linked its nearly $3 billion coronavirus aid package for Ukraine to the land question.

A hard battle

The government bill, sent to the Verkhovna Rada in late 2019, was advertised as a miracle cure. Allowing land sales, its proponents claimed, would prompt robust growth of Ukraine’s GDP – by adding to it as much as 2-3 percent during the year following the introduction of the law. The president’s experts also claimed that the reform would open the floodgates of foreign direct investment. They assessed that up to $10 billion worth of financing could flow into Ukraine’s agricultural sector.

Nonetheless, resistance to the measure was formidable. In November 2019 and on February 6-7, during the bill’s first and second readings, the atmosphere inside the Verkhovna Rada building and on the streets of Kiev was tempestuous.

The government compromised, accepting some of the opposition’s demands in exchange for votes.

Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister and one of the most recognizable figures in Ukrainian politics, blocked the seat of the parliament chairman to try to hinder the bill’s passage. Along with Ms. Tymoshenko’s Fatherland (Batkivshchyna) party, all opposition members locked arms against the reform, from former President Petro Poroshenko’s European Solidarity to the veterans of exiled ex-President Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions. Only Mr. Zelenskiy’s deputies, from the Servant of the People party, supported the draft.

Outside the parliament, thousands of protesters held up placards and banners with statements such as, ‘‘The sale of land is the nation’s genocide,’’ or ‘‘Foreigners will seize the land. Our children will be slaves in their country.’’ In the end, however, the bill passed. The government compromised, accepting some of the opposition’s demands in exchange for votes, including from former President Poroshenko’s camp. The law was adopted by the Verkhovna Rada on March 31.

In July 2021, after nearly 20 years of being in force, the moratorium on land trading will be lifted throughout the country. President Zelenskiy can claim this as a political success. The law grants the right to purchase land to the state, local governments, Ukrainian citizens and companies registered in Ukraine. Sales of real estate to foreigners remain forbidden. They can legally become landowners in exceptional cases only, like through inheritance.

The reform will determine the final shape of the country’s entrenched oligarchy.

Liberalization will be gradual. In the beginning, during a two-year transition period, individuals will be able to acquire lots of up to 100 hectares. The ban on the sale of approximately 10.4 million hectares of state-owned land will remain in force. In the next stage – from July 2023 onward – land transactions of up to 10,000 hectares will be allowed, but only for companies.

Foreigners are supposed to be excluded from land transactions until a referendum decides on the issue. In practice, it is unlikely that it will ever be held. Even if a vote took place, permission to sell farmland to foreigners would not be granted by the voters. However, preliminary reviews of the legislation suggest that it contains enough loopholes to make land transactions for both the wealthiest Ukrainians and foreign investors possible. In Ukraine’s agribusiness sector, the 100 largest companies already use a total of 6.6 million hectares, or some 20 percent of the country’s agricultural land. A quick transition from leasing property to ownership can be expected in these cases.

Farmland, according to the new legislation, can be bought by agricultural companies, but only those that had been registered in Ukraine for more than three years before the law went into force and had already signed lease contracts. The law also stipulates that individuals and companies from the countries that are under Ukrainian sanctions – for example, Russia – can be banned from land transactions.

Such provisions, however, have only symbolic significance – the richest Ukrainians and Russians will find ways to circumvent the rules.

Scenarios

Looking ahead, the next phase, the implementation of the legislation over the next few years, will prove critically important.

First and most obviously, the land market reform will determine the final shape of the country’s entrenched oligarchy. If a handful of the richest citizens are allowed to snatch the best chunks of the most valuable land, the oligarchic order in Ukraine – characterized by the dominance of individuals over selected branches of the economy – will be cemented.

An agricultural system resembling the latifundia of 16th- and 17th-century magnates could be catastrophic to the modern Ukrainian state, as its regions would be subordinated to particular oligarchs, stunting the country’s economic, social and political development.

Another concern is Ukraine’s relationship with the EU. Its new agricultural setup can either emerge as a threat – a low-cost, high-output competitor for food producers in western Europe – or take another form, more compatible with Europe’s existing system.

If the former scenario materializes, Ukraine's political relations with countries such as Poland or Germany will become strained – which, in turn, will reduce these countries’ readiness to support Ukraine’s EU accession ambitions. The EU’s history shows that disputes over agriculture often translate into political tensions between member states. Ukraine is already one of the top three exporters of farm products to the EU. In 2019, the value of these exports reached 7.3 billion euros.

The reform’s implementation will also shape social developments in Ukraine’s rural areas: how depopulated they will become and if, for example, a smaller-scale, organic-farming sector will be allowed to emerge and thrive. Such a sector would employ large groups of people. Jobs can be created in mountain and agritourism in the Carpathians, with regional foods processing and the associated services. Additionally, profitable cross-border cooperation usually develops in the presence of family firms and other small-scale enterprises.

If, on the other hand, the Ukrainian government opts instead for a significant expansion of the large-scale, capital-intensive commercial farming sector, the development of the Ukrainian middle class and the empowerment of rural communities will be impaired.