The future of Ukraine’s energy transit status

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline threatens to circumvent Ukraine, which has offered lowered gas transit rates to Gazprom if it scraps the project and allows other exporters to pass through the country. Russia is uninterested in such a deal, but rising forecasts of European gas demand mean that the Kremlin must continue to rely on Ukraine.

Facts & figures

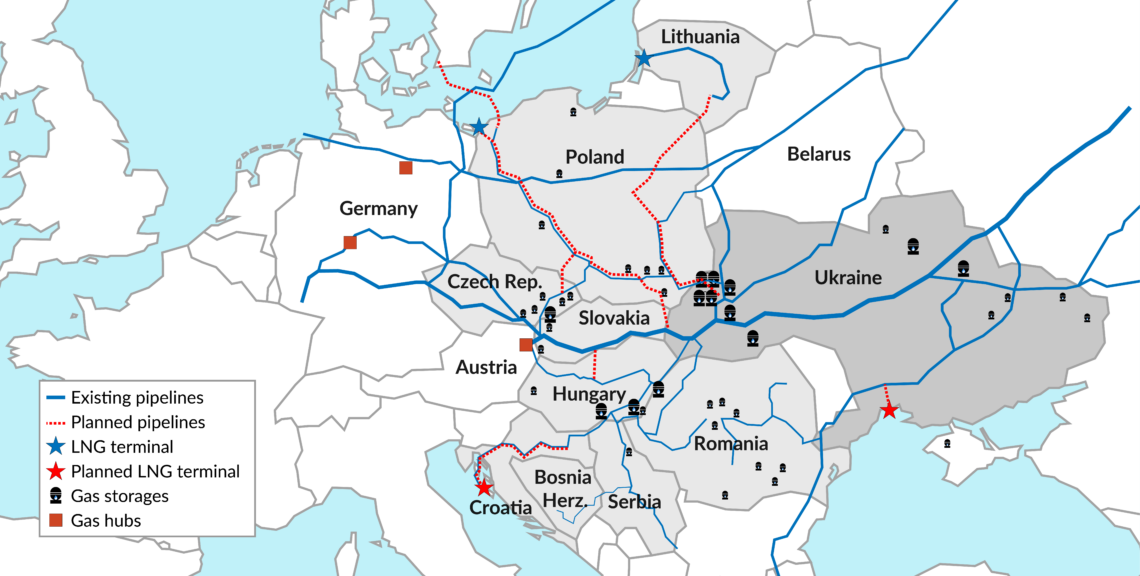

Gas infrastructure in Ukraine and the region

In a nutshell

- Ukraine must reach a new deal with Russia to continue transiting gas to Europe

- Russia is uninterested in a grand bargain but may need to rely on Ukrainian pipelines given rising European demand

- New pipelines could allow Russia to circumvent Ukraine, but they are not yet completed

- Energy sector reforms and compliance with new EU regulations could benefit the Ukrainian gas industry

With a key contract expiring in 2019, Ukraine’s status as the conduit for Russian gas to Europe is uncertain.

European Union member states, the European Commission and German Chancellor Angela Merkel have all insisted that Ukraine’s gas transit status needs to be maintained, not only past 2019 (when Russia’s current agreement with Ukraine ends) but also in the long term. The European Commission has repeatedly called for talks to seek a guarantee from Russia on Ukraine’s future gas transit status and other related issues beyond next year.

Despite assurances from Russia that it is interested in an extension of the status quo, at least until Nord Stream 2 and the two TurkStream pipelines are completed, the negotiations have yet to come to an agreement.

Rising tensions

Russian President Vladimir Putin has resisted a long-term deal, setting conditions on new fixed transit prices and a suspension of payments owed to Ukraine. The Kremlin appears to be playing for time until it can simply circumvent Ukraine with other supply routes.

In a February 2018 ruling over the gas transit contract, the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC) ruled that Gazprom owed $4.6 billion to Ukraine for unpaid gas volumes. In December 2017, the same court awarded Russia around $2 billion from Ukraine over contractually obligated gas purchases in 2014 and 2015 that were not made. Between the two rulings, Gazprom owes $2.56 billion to Naftogaz, Ukraine’s national oil and gas company.

Facts & figures

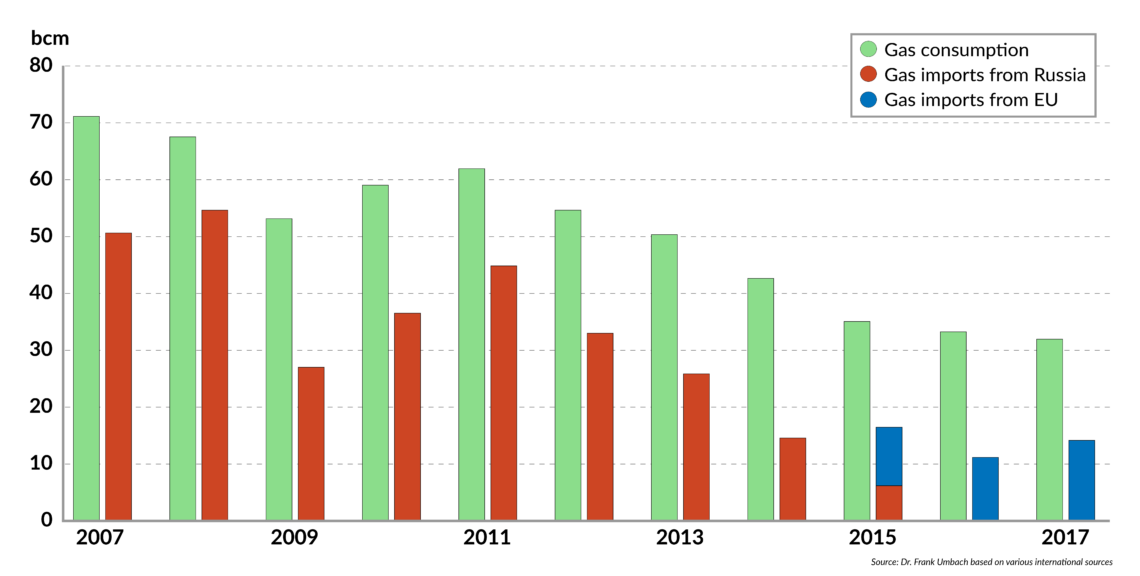

Ukrainian gas consumption and imports from Russia (2007-2017)

Ukraine has continuously decreased its Russian gas imports since 2015. By March 2016 it ended all Russian imports for its own consumption and replaced them with gas from its European neighbors, via reversed-flow capacities. Yet, because of Ukraine’s existing contract with Gazprom and the 2017 arbitration ruling, it still has to purchase 4 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian gas per year.

On March 1, 2018, Naftogaz made an advance payment for 0.5 bcm and prepared to reduce other gas imports. Gazprom abruptly decreased the gas pressure to the Ukrainian transmission system. Coming during a period of unseasonably cool temperatures in Europe, the move caused another state of emergency in Ukraine and triggered new supply concerns on the continent.

Ukraine reacted by decreasing national gas consumption and signing a contract with European neighbors for expensive emergency gas imports for maintaining full gas supplies to Europe. It signaled its solidarity with Europe and its political, as well as commercial, reliability.

Gazprom, in contrast, announced that it would unilaterally terminate the gas supply contract with Naftogaz and sharply criticized the arbitration decision as unjust. The EU and even some of Gazprom’s European partners warned Russia to restore full gas supplies to Ukraine and back away from canceling the contract, to avoid undermining its reputation as a reliable energy partner.

Either way, the contract is set to expire at the end of 2019, leaving three possible scenarios for Ukraine’s gas transit future.

No deal

The new Russian gas pipelines Nord Stream 1 and Blue Stream, as well as those previously planned but canceled like South Stream, have been designed to circumvent Ukraine. That makes Russia less dependent on Ukraine, but it could also increase the pressure on Ukraine and advance the Kremlin’s economic and geopolitical objectives.

Facts & figures

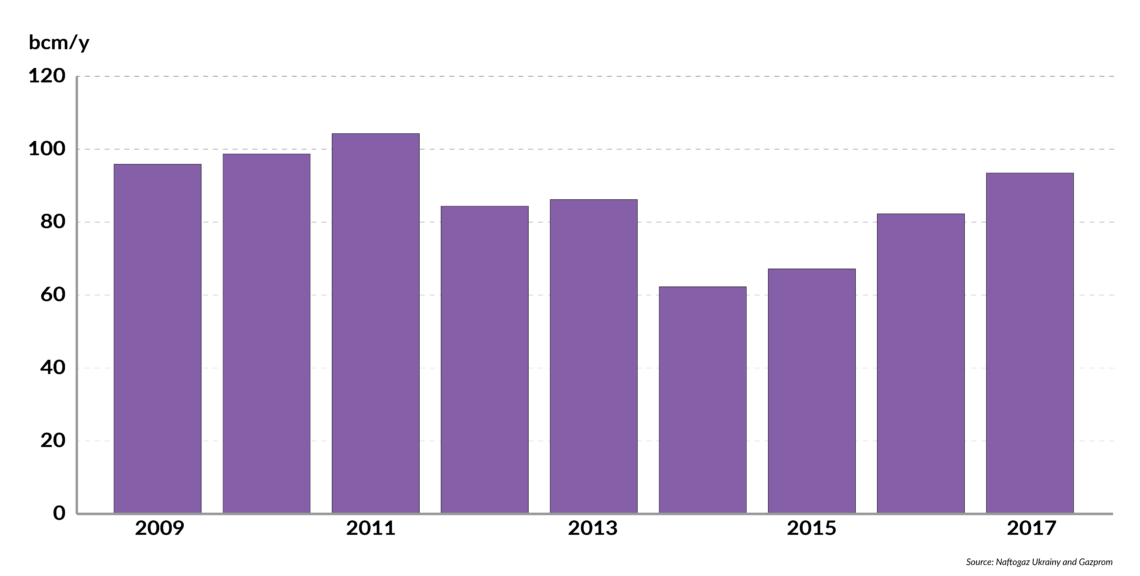

Russian gas transit volumes via Ukraine 2009-2017

In 2017, Russia exported 165 bcm of gas to the EU and 197 bcm of gas to Europe as a whole, including Turkey. Half of that gas transited through Ukraine. At 93.4 bcm, the transmission of Russian gas via Ukraine was at the highest level in seven years.

That earned Ukraine about $3 billion in revenue or around 20 percent of its state budget and three percent of its GDP. That could be lost if Ukraine’s transit status ends with the completion of Nord Stream 2 (which has a capacity of 110 bcm per year) and TurkStream (31.5 bcm per year), as well as expanded LNG exports to Europe from other countries.

Nord Stream 2 won’t become operational by 2019, when Russia’s contract to supply gas to Europe via Ukraine expires. Russia will be forced to export gas to Europe through Ukraine at least until 2020-2021. Even with the TurkStream pipelines finished, Europe’s imports will still depend on figuring out which Southeast European countries will be able to import Russian gas from Turkey, and how.

In July 2018, Ukraine officially offered much lower rates for transiting Russian gas to Europe in an initial five-year period (2019-2024) if Nord Stream 2 is not built, and if Gazprom ends its monopoly on pipeline exports via Ukraine to allow Central Asian producers use of its network.

New 2017 EU regulations set tariffs for gas transmission at about $2.17 for every 1,000 cubic meters of gas per 100 km, which is about a fifth less than the tariffs in the Naftogaz-Gazprom contract, and less than half the average cost of gas transmission established by Ukrainian regulators in December 2015. Yet the Kremlin and Gazprom still will not accept the Ukrainian offer under the condition that Russia gives up Nord Steam 2.

Temporary need

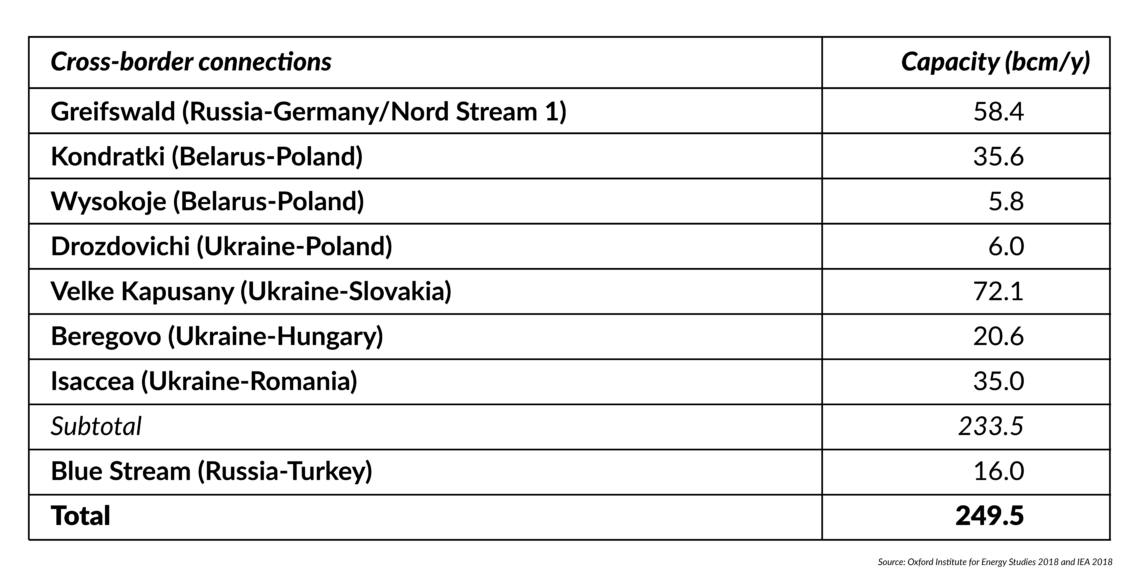

Until Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream are completed, Russia will remain dependent on Ukraine. Combined, both will account for more than 140 bcm per year circumventing Ukraine (including Turkey, or 126 bcm to Europe without Turkey). In June 2018, Russia announced it would modernize the gas transit infrastructure in Belarus, which has a capacity of around 40 bcm per year. Russia will invest $3.5 billion in Belarus’ gas sector through 2020, including for new capacity that could match Russia’s entire annual gas exports to the EU.

If Russia’s gas exports do not increase further in the next two decades, it would need Ukraine’s gas transit only during peak times, at a level of 10-15 bcm per year. However, if any of the newly built pipelines need larger repairs (as regularly happens) or if Europe’s gas import demand rises further and is not covered by non-Russian LNG imports, Gazprom would need to rely on Ukraine for gas transit or otherwise seek new gas export capacities.

Facts & figures

Russia-Europe gas pipeline connections

This could result in new export capacities such as two additional TurkStream pipelines (as originally planned); a Nord-Stream 3 pipeline (as some Russian gas experts have discussed); expanded Yamal pipeline capacities through Belarus (“Yamal 2”); or expanded LNG exports to Europe.

A temporary option that would supply 10 to 15 bcm per year via Ukraine might serve Russia’s short-term interests. But that would undermine Moscow’s long-term geopolitical influence, by further strengthening Kiev’s efforts to achieve gas import diversification and independence.

Long-term future

Given optimistic Gazprom forecasts of demand in Europe, Russian energy minister Alexander Novak has conceded that Ukraine’s gas transport system may contribute to rising Russian exports to Europe by 10-15 percent over the next decade.

But President Putin has made any grand bargain dependent on an (unspecified) fixed transit price and a suspension of the arbitration ruling that awarded $2.56 billion to Ukraine. The Kremlin appears to be playing for time to create a fait accompli, when it will have built sufficient gas supply options for Europe that circumvent Ukraine.

Any compromise between the Russian, Ukrainian and EU positions on Ukraine’s transit status past 2020-2021 also depends on energy reforms (i.e. the unbundling of Naftogaz) and future European gas demand, whose forecasts vary considerably. Naftogaz is still Ukraine’s largest taxpayer and has funded almost a fifth of the national state budget through September 2018.

The Kremlin appears to be playing for time until it can simply circumvent Ukraine with other supply routes.

The decoupling of gas transmission from its trade and supply business is not just important for complying with the EU’s third energy rules and practices, which Ukraine must do as a member of the Energy Community, but also for Ukraine’s future transit flows and the setting of tariffs.

Ukraine’s current tariffs are more expensive than the offered tariffs for Nord Stream 2 and are neither transparent nor predictable. Compliance with EU regulations is not in the interest of some Ukrainian oligarchs and corruption-prone officials, nor in Russia’s; a non-reformed Ukrainian gas sector offers more opportunities to influence Ukraine’s gas policies and prices.

According to a World Bank report, two percent of firms control a quarter of the assets of all Ukrainian companies. Eleven “politically exposed persons” own a quarter of all national oil and gas special permits. Ukraine’s oil, gas and coal sectors are still controlled by political cronies and oligarchs, some of whom have close ties to Russia. The lack of transparency over who really runs the industry hurts fair competition, market liberalization and foreign investments.

Together with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the EU has strongly supported Ukraine’s energy and gas market reforms. The new management of Naftogaz has also strongly advocated them, which include the unbundling of transmission, storage, distribution and production activities as well as price liberalization in the retail market and of the upstream tax regime. But the Ukrainian government has repeatedly blocked, hampered and postponed those reforms. They are essential for Ukraine as an efficient, sustainable and credible energy partner with Europe.

Naftogaz, its new independent supervisory board and the Ukrainian government have agreed on a clear road map for the unbundling process. But that will start only at the beginning of 2020 when the existing transit contract with Gazprom expires. Contrary to Russian interest, it will open Ukraine’s gas transmission network for third parties such as gas exporters from Central Asia.

The decline of Ukraine’s gas transit status has not mitigated underlying tensions with Russia.

Naftogaz and the government hope to use the new regulations to enable them to receive reliable information about gas volumes consumed by its households, which is impossible under the current opaque system. Some gas consumed by protected consumers is sold by nontransparent intermediaries on the commercial market. As a result, Naftogaz is losing revenues domestically while the government is effectively funding excessive subsidies. Until all European regulations are complied with, Naftogaz’s only real source of revenue is the present transit fees, which explains its support of the reforms.

Strategic perspectives

The Russian-Ukrainian gas relationship is less commercial than geopolitical, and the decline of Ukraine’s gas transit status has not mitigated the underlying tensions. The 2017 and 2018 arbitration rulings will not end the conflict, and a grand bargain is not perceived as in the Kremlin’s strategic interest. But neither is the status quo, and Russia will push Kiev for additional gas import options, such as the Trans-Balkan Pipeline or the planned BRUA and Eastring pipelines.

Ukraine will benefit from the construction of a new Polish-Ukrainian gas interconnector with a capacity of 5 bcm (though it will come online only in 2020), from a greater use of Poland’s Swinoujscie LNG terminal, and Norwegian gas via its planned 10 bcm Baltic Pipe.

Ukraine also needs to speed up its energy reforms and other goals. Ukraine wants to become independent of any gas imports and start exporting Ukrainian gas to its European neighbors starting in 2020, but that requires more domestic production. Kiev may fail to increase its gas production from 20 bcm per year in 2017 to 27-28 bcm per year, despite its proven reserves of 600 bcm that cover 20 years at current production levels. Kiev also may not be able to decrease its own gas consumption from around 32 bcm per year to 27-28 bcm per year by 2020.

Furthermore, Ukraine’s coal imports almost doubled in 2017 compared to 2016. Russia provided 56 percent of total supplies, and its supply of nuclear fuel was up 69 percent. Ukraine needs to adopt more ambitious targets for renewable energy, which now stand at 11 percent of energy consumption by 2020 and 25 percent by 2035. This highlights the need for a comprehensive transformation of Ukraine’s power sector, which has only just started.