The future of the West’s global security strategy

Recent events will trigger a strategic alignment that views both Russia and China as parts of the same problem for the West.

In a nutshell

- The West is facing dangerous challenges in Europe and the Asia-Pacific

- This calls for integrated and coordinated security policy responses

- Responding to Russia and China in combative fashion is among the options

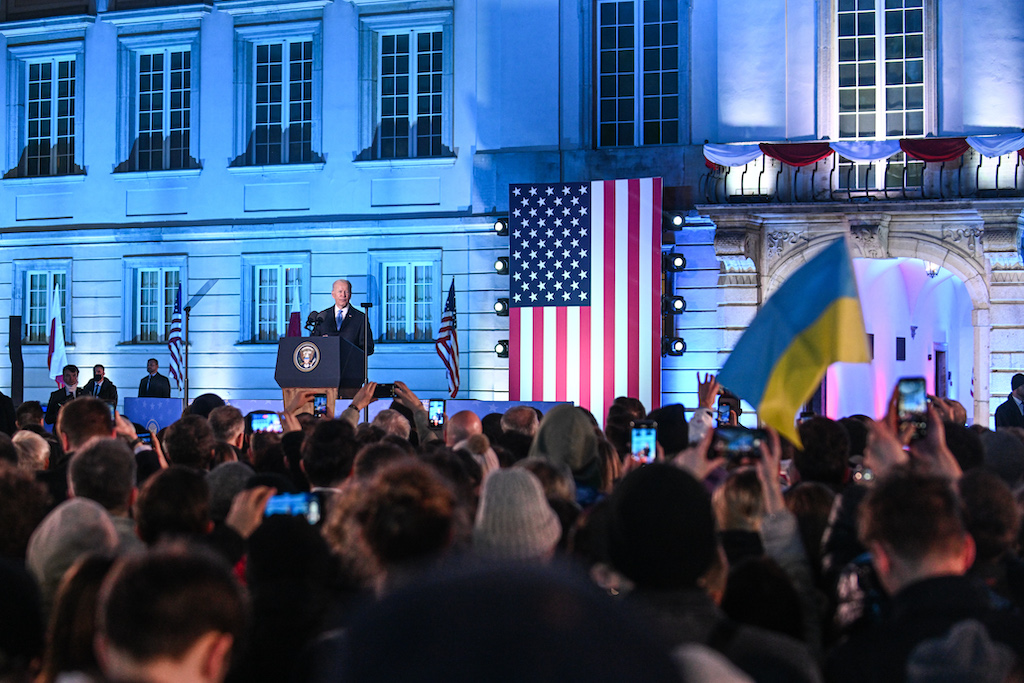

Since the mid-20th century, the West has not been as perplexed as it is today about simultaneously addressing the challenges to vital interests in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters. The Russian invasion of Ukraine brought the most destructive fighting since World War II to Europe’s doorstep. At the same time, the conflict increased fears that the regime in Beijing might take similar actions against Taiwan.

These concerns have renewed the debate over how Western powers will balance the protection of their global interests in these two critical areas of competition. Recent events will likely trigger a strategic alignment that views both Russia and China as parts of the same problem. This assessment will lead to more integrated and coordinated security policy responses by a coalition of allies in the Atlantic community and the Indo-Pacific region.

The shape of things to come

Unquestionably, the issue of Ukraine and Taiwan has triggered a significant reexamination of global peace and security.

There seems to be a consensus among Western governments that the Russian invasion of Ukraine does not represent limited territorial expansion by Moscow. Russian President Vladimir Putin would not have risked so much for such limited objectives. Instead, the invasion has been seen as a part of a deliberate effort to expand Russia’s sphere of hard power influence that would extend to other post-Soviet states and Central Europe, including members of the NATO alliance. Atlantic nations might differ in their willingness to support Ukraine or punish and deter Russia, but none have offered a defense of Mr. Putin’s actions as appropriate or legitimate.

Taiwan represents a more significant concern from a geostrategic perspective.

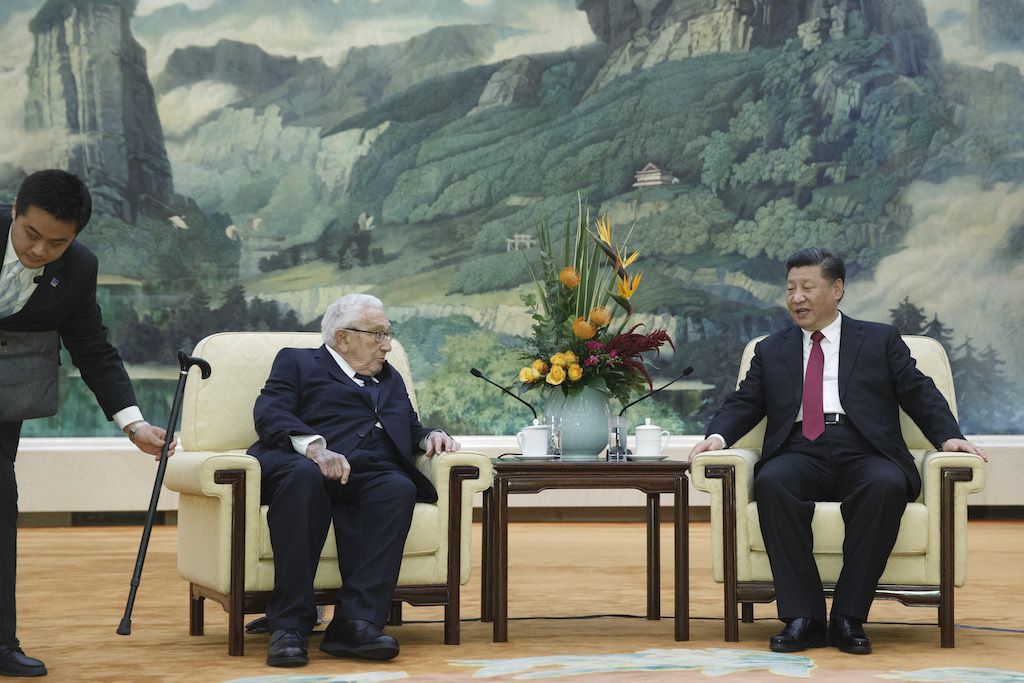

This war also has implications for how the Atlantic community assesses the role of China in Europe. Again, few dispute that China did little to restrain the Russian invasion. Indeed, through the China association in the 17+1 framework (cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries) and other initiatives, Beijing sought individual bilateral relations that strengthened its influence in Europe, undercutting European solidarity in developing a common position on China. Most notably, the Chinese government tried to mobilize other European nations to punish Lithuania for strengthening bonds with Taiwan.

In this respect, a swift Russian victory would have arguably accelerated the fragmentation and distraction of Europe, strengthening China’s influence on the continent. However, the protracted war against Ukraine has accelerated mistrust against Beijing in some European quarters.

Further, China’s aggressive stance toward Taiwan has also raised new concerns over Beijing’s long-term strategy. These worries about Taiwan’s future are manifested in calls to protect Taiwanese democracy or its critical role in global supply chains as a provider of microchips used to produce many consumer and industrial products.

However, Taiwan represents a more significant concern from a geostrategic perspective. It is a critical part of the “first island chain.” Beijing’s takeover would allow China to control a vital maritime corridor in the Pacific. Among other outcomes, South Korea and Japan would be isolated.

Together, these actions seem to be clear evidence of more aggressive postures by China and Russia and increasing cooperation between the two powers. One obvious conclusion would be that the “rules-based” order trumpeted for years as a vital factor in ameliorating global competition has proven inadequate.

There is vociferous debate over how to respond to this reality. One argument is for returning to the status quo of seeking a balance of “cooperation and competition” with both countries: seeking cooperation on shared concerns to build trust and confidence and competing where it is unavoidable. Another proposal is to create strategies for pressuring China and Russia to return to the norms of rules-based order. Yet another option argues for treating these nations as adversaries and responding with combative designs ranging from “decoupling” to containment and regime change.

An American pivot to Asia alone seems less likely than ever.

One key variable in determining future strategies will be how the West and its allies opt to treat China and Russia. They can be seen as discrete concerns, or Russia may be treated as an extension of China’s destabilizing activity. Several factors will likely influence the choices to be made.

Scenarios

U.S. focus

There is a consensus in the United States that it lacks both the hard and soft power to take on Russia and China independently. Debates are conducted in the U.S. on whether to focus on China to the exclusion of Russia, or if the U.S. should opt for more isolationist or hands-off policies, but these are not likely to happen. In both theaters, the U.S. has allies who will insist on its engagement and commitment.

In the Asia-Pacific, key nations such as South Korea, Japan, Australia and India have built their response around an assumption that the U.S. would be an engaged international partner. At the same time, there is little question that one of the lessons of the war in Ukraine will be the central role the U.S. plays in NATO and that NATO remains vitally important to the collective security of the transatlantic community. An American pivot to Asia alone seems less likely than ever.

Climate

Decisions on how to address climate action will significantly impact future choices. Action plans based on the transition to renewable green energy directly conflict with sustained economic growth initiatives and reliance on energy supplies from adversarial powers. How these competing goals are reconciled will define the extent of cooperation among the nations that want to achieve sustainable growth without increasing the reliance on and interdependence with China and Russia.

Inter-theater cooperation

The transatlantic community and the Indo-Pacific feature different security architectures. Further, both engage differently in the Middle East, another critical theater, where competition with Russia and China is also a factor. There have been nascent efforts to harmonize interests in the two theaters or leverage actions in one theater to benefit another.

For instance, several European countries are increasing engagements with Taiwan. Nations with long-standing interests in the Indo-Pacific, including the United Kingdom and France, are ramping up their engagement in the region. Recent examples include the British participation in AUKUS, a trilateral security pact with Australia, and the U.S. consent to share some of its leading-edge nuclear submarine technology with Australia.

Conversely, Japan and South Korea are increasingly looking at partnerships and investments in Europe. Asian nations, for example, are looking at the possibility of investing in the Central European Three Seas Initiative, which aims to develop infrastructure in the region. India has added a “Look West” policy that seeks expanded cooperation in the Middle East and European nations.

These very partnerships will likely be the cutting edge of harmonizing cross-theater cooperation. One key trend to watch is whether such relationships evolve into multilateral cooperative efforts. And conversely, how the Chinese- and Russian-led multilateral structures will fare. One nation, Lithuania, withdrew from Beijing’s 17+1 framework in 2021.

International organizations

Chinese influence and manipulation of international organizations have become an increasing concern. Among the most notable controversies is the dispute over Chinese influence in the World Health Organization on Covid-19 response. And Australia pioneered an effort to scrutinize the Russian exploitation of the authorities of Interpol. At present, there is little consensus on a strategy to deal with these concerns. However, the resentment over Chinese activities in opposing action against Russia due to its invasion of Ukraine has driven more attention to the issue.

Military investments

One early lesson to take from the war against Ukraine is the value of conventional and strategic – nuclear and missile defense – deterrence. There is a clear recognition that traditional “hard power” is critical in dealing with both China and Russia. While the Chinese military has not been tested in significant combat in recent decades and the Russian armed forces have performed poorly in their operations against Ukraine, nations are becoming less willing to discount future military threats by either actor. The extent, nature and duration of defense investments will be another important indicator of future strategic cooperation.

Security cooperation

After the Ukraine invasion, many states currently involved in territorial disputes with Russia and China will be reconsidering their future security partnerships. In recent years, the tendency has been not to seek formal security treaties and binding guarantees. Nations preferred the flexibility of cooperation, seeking, for instance, closer engagement with the U.S., China, the European Union and Russia in various combinations – or all at the same time. This approach failed to deter massive kinetic conflict in Ukraine. Current instruments, such as the NATO partnership process, will increasingly be seen as inadequate. In the South Caucasus and Central Asia, and in Europe from Sweden to Finland, Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, states may seek new or alternate frameworks to achieve security guarantees.

What now?

The indicators listed above will likely point to the degree of cross-theater cooperation in the future. The most likely scenario is that Russia and China will continue to press more muscular policies, making even more clear that the concept of a responsible rules-based order is untenable. Consequently, this will most likely drive increasing cross-theater cooperation that views Russia and China as a common threat to order. The shape of any common strategy to mitigate future risks is yet to emerge.