Two scenarios for the future of U.S.-China relations

The U.S. no longer sees any potential in partnership with China. The two countries have entered into a strategic competition that could quickly become a cold war-style confrontation. Negotiation on the biggest economic sticking points could ease tensions, but only for the short term.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. and China are strategic competitors

- American policy is moving toward a greater confrontation with Beijing

- If economic ties continue to deteriorate, a quasi-cold war is possible

- The most likely scenario is an engagement that de-escalates tensions

In the United States, tension has been building since at least the 2000 presidential election between the concepts of strategic competition and partnership with China. It is clear from President Donald Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy that the former has won out. U.S.-China relations have entered a new, competitive era. Exactly what shape this competition takes, however, is a crucial issue. There are two possible scenarios.

Confrontation

The first is quasi-cold war. There are indicators that the U.S. has moved into a period of “whole of society” confrontation with China. Vice President Mike Pence’s October speech to the Hudson Institute in Washington, in which he cited a “new consensus … rising across America … to defend our national interests and most cherished ideals,” points in this direction.

Recent policy decisions appear to bear this out as well. The Trump administration has doubled down on U.S. naval operations in the South China Sea, conducting twice as many freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) in two years as the Obama administration did in its last four. Their content has also been bolder – several of these FONOPs have become headline news. Beyond this, there were the sanctions imposed on the Chinese military for its purchase of Russian equipment, indictments of Chinese intelligence officials for stealing trade secrets, a new prohibition on sales to a state-owned Chinese technology company, as well as the withdrawal of an invitation for China to participate in the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC), the world’s largest multilateral naval exercise.

In response to the geopolitical threat represented by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the U.S. has created the International Development Finance Corporation – an organization that will command twice as much funding than the organization it replaces (the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, or OPIC). The U.S. is also seeking to counter Chinese infrastructure spending by better coordinating development with its regional allies and partners, especially Australia, India and Japan.

The American private sector is already a bigger investor in the Asia-Pacific region than China is.

A plan to spend $131 million on technical assistance for Indo-Pacific countries was met with some ridicule from Beijing – the comparison with China’s own trillion-dollar BRI being all too stark. Yet, it and the $400 million Indo-Pacific Transparency Initiative announced by Vice President Pence at APEC in November are indications that Washington is serious about pushing back against Chinese influence. In terms of government dollars, none of this can match Chinese resources, but as Vice President Pence and other administration officials have pointed out, the U.S. does not intend to compete in kind with China. The American private sector is already a more significant investor in the region than China is. The U.S. seeks to facilitate and leverage this.

On the potential flash point of Taiwan – the U.S. has become proactive in support of the island’s de facto autonomy. The “Taiwan Travel Act,” a nonbinding bill encouraging increased government and military contact with Taiwan, was passed unanimously by Congress. Although the bill would have become law whether or not President Trump signed it, he made a point of doing so publicly.

The administration has also made two major arms sales to Taiwan, with another one widely rumored to be in the works, and it has given approval for American companies to provide technology for Taiwan’s submarine program.

Of course, Beijing has reacted negatively to the U.S. support for Taiwan – as it always does. China’s Defense Minister General Wei Fenghe went so far as to publicly threaten war “if anyone tries to separate Taiwan from China.” The Chinese have also reacted negatively, and sometimes aggressively, to U.S. activity in the South China Sea – the near collision of the Chinese destroyer Luoyang with the USS Decatur on September 30 being the most recent example.

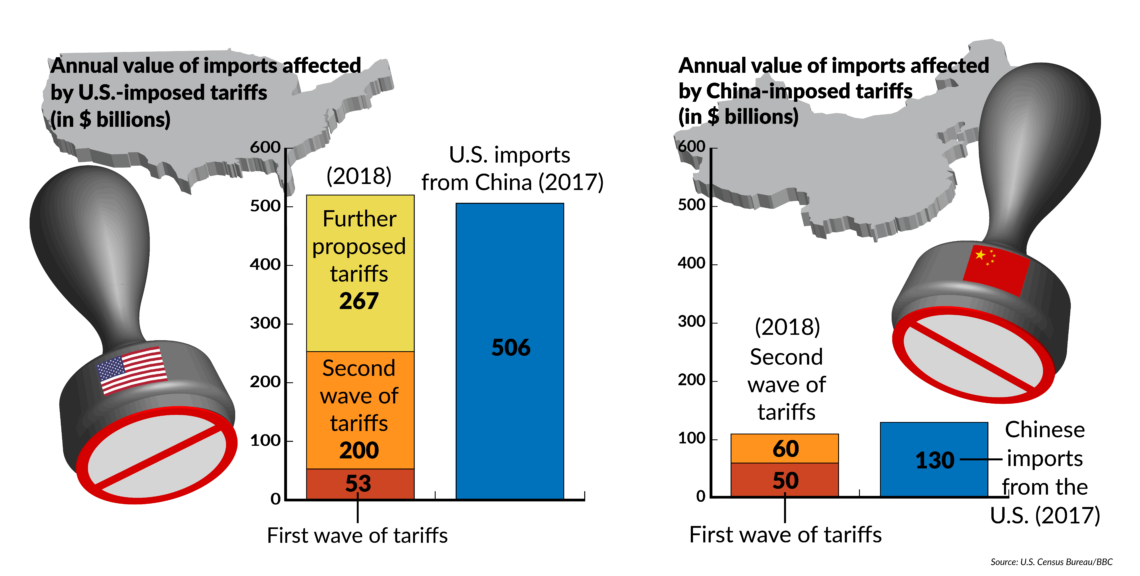

Facts & figures

U.S.-China tit-for-tat tariffs

Assertive posture

Chinese reaction to the U.S. is only part of the dynamic, however, and not the most critical part. The Trump administration believes its new assertive posture is an overdue response to the change in China’s behavior, which has become especially clear since the financial crisis of 2008. Beijing, in the White House’s view, has long been engaged in a “whole of government” offensive aimed at driving the U.S. out of the Pacific. The evidence includes the trillion-dollar BRI, influence operations in American universities, cyber espionage, concerted efforts to isolate Taiwan, the island-building campaign in the South China Sea and pressure on Japan in the East China Sea.

The trade conflict between the U.S. and China adds a more combative context to all the discrete policy decisions. Many in China’s policymaking circles have long believed the U.S. ultimately would not accommodate its rise as a great power. The pace, volume and ongoing nature of the trade measures taken so far by the U.S. confirm those fears. Others in Beijing are waiting to see the extent of the American actions on trade and other issues before drawing this conclusion.

The Chinese want to make a deal. If one is not forthcoming and the economic relationship continues to deteriorate, the quasi-cold war scenario will become a reality. Very much unlike the Cold War with the Soviet Union, though, the U.S. will find few allies and its influence in the region will diminish.

Political competition, economic truce

The second scenario – and the more likely one – turns on economic issues.

The legal basis for most of the import tariffs levied on China is its violation of American intellectual property rights. The specific complaints were Beijing’s use of joint-venture requirements, foreign investment restrictions and other administrative processes to coerce technology transfer; discrimination in licensing; technology transfer facilitated through investment in the U.S.; and commercial cyber espionage. The discrimination issue is being addressed through the World Trade Organization and the investment issue through the reform of U.S. foreign investment regulations. That leaves the cyber problem (which Chinese President Xi Jinping promised former President Barack Obama that Beijing would address back in 2015) and the coercion issue.

A process for addressing economic issues could establish the basis for an agreement with the U.S.

These are not the only trade issues at stake, however. Others include Chinese data localization, standards, subsidies and the advantages given to state-owned Chinese companies. In May, the U.S. delivered 140 specific trade demands to the Chinese. Beijing reportedly has said it is prepared to address a third of these, a third it is willing to discuss, while the final third is off limits.

Concrete solutions to the intellectual property rights complaints, fast movement on some of the 140 complaints, and at least a process for addressing the third of the issues open for discussion could establish the basis for an agreement with the U.S. This, in turn, could result in a pause in trade tensions. Removing the tariffs already imposed will be a challenge, but a deal could at least preclude the planned imposition of more on January 1, 2019, and President Trump’s threat to impose new tariffs on the entirety of America’s $506 billion imports from China.

There is ample precedent for such a drawdown in trade tensions. There is the agreement reached between President Trump and European Commissioner Jean-Claude Juncker and a deal early on in the Trump administration to institutionalize a wide-reaching economic dialogue with Japan. Both cases, initially represented as “truces” in trade disputes, have progressed to a more formal discussion of trade agreements. There is also the case of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the result of an extremely contentious effort to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). And there is the successful conclusion of amendments to the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS).

Tensions surrounding political and security matters between the U.S. and China will likely continue.

In this scenario, the tensions surrounding political and security matters between the U.S. and China would continue within the “strategic competitor” context. There are strong constituencies within the Trump administration and Congress that are concerned about China’s stance on Taiwan, the South China Sea and human rights, among other issues. The need for a sufficient response to China’s BRI and greater coordination with allies and partners through mechanisms like the quadrilateral dialogue has already been fully absorbed into the administration’s strategic planning.

China’s compliance with its trade promises would be subject to constant review and criticism; trade disagreements would occasionally flare. However, reaching agreement on a process for addressing them would take the menace – from the Chinese perspective – out of the American approach. This would enable a more regular, predictable schedule of consultations: the sort of engagement the Trump administration laid out in its first months.

This will not, however, represent a return to the status quo ante. There has been a sea change in the U.S.-China relationship. While it may not be headed for a quasi-cold war in which economic relations become part of a bigger strategic picture, the best that one can hope for is that the countries will avoid armed conflict and find minor areas of cooperation.