The U.S.’s never-ending pivot to Asia

Two decades after outlining the need for a greater military presence in Asia, U.S. forces have yet to be redeployed.

In a nutshell

- The idea of a pivot to Asia has been around since the early 2000s

- In practice, U.S. military presence has remained unchanged

- Economic and security hurdles are preventing a major shift

Washington continues to promise, debate and discuss a “pivot” to Asia, addressing growing concerns over China’s rise as a disruptive global power. Yet, 20 years since the issue was first outlined, the United States’ global military, economic, and diplomatic footprint looks remarkably unchanged. Absent a major regional conflict, that posture is not likely to dramatically shift anytime soon.

Responding to the rising dragon

In 2006, then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld called for greater focus on China in the Quadrennial Defense Review, even though Beijing was not mentioned by name. Rethinking America’s global posture in the post-Cold War world was a hotly debated topic. Thomas Barnett’s “The Pentagon’s New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century” (2005) argued for placing more emphasis on a geopolitical belt of ungoverned space and failing nations. In contrast, the influential Department of Defense Office of Net Assessment consistently advocated for a substantive rebalancing of forces to contain China.

In the end, the attention of the presidential administration of George W. Bush was largely consumed by the Global War on Terrorism. Washington attempted to improve relations with China by, for instance, supporting its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. The Quad initiative between Australia, India, Japan and the U.S. was also disbanded after Beijing’s complaint over a single meeting at the sub-cabinet level.

While the Chinese regime’s military influence is primarily regional, its economic, diplomatic, intelligence, cyber and political influence is global.

President Barack Obama famously formally introduced the proposals for a “pivot to Asia.” The announcement, however, came after the U.S. declared its forces would withdraw from Iraq, and was mostly intended more to signal that Washington was not disengaging from global affairs.

In practical terms, little else changed in U.S. policy. For instance, while President Obama continued to reduce U.S. forces in the Middle East and Europe, there was no commensurate increase in Asia. The only real developments were ongoing defense posture adjustments, not new initiatives. Indeed, President Obama placed even more emphasis on seeking cooperation with China where possible.

While President Donald Trump entered office with a dramatically more aggressive attitude toward China, his policies focused on trade issues, intellectual property theft, malicious influence on U.S. universities, cybersecurity, telecom infrastructure, and other bilateral matters. President Trump did push forward to revive the Quad, but this was hardly a pivot, since the president also had diplomatic initiatives in the Middle East, Europe and the Western Hemisphere.

Facts & figures

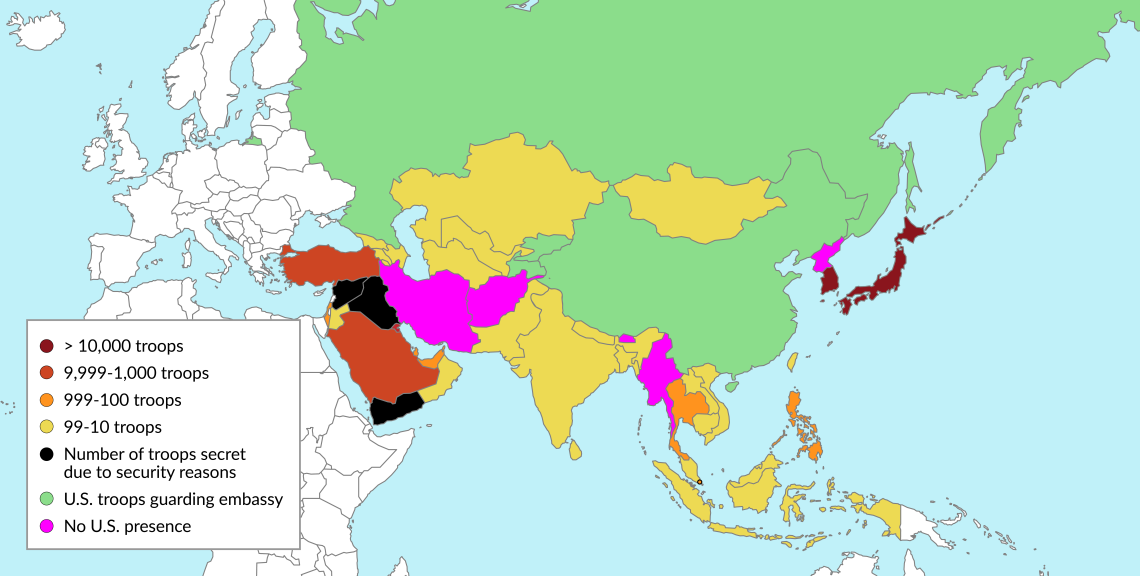

U.S. bases in Asia as of 2021

Upon his election, President Joe Biden reversed many of the Trump-era initiatives. Even though the administration prominently featured concerns about China in its 2022 National Security Strategy (2022), the approach remains remarkably similar to Mr. Obama’s of “compete where we must but cooperate where we can.” Indeed, even now the U.S. is pressing for cooperation with Beijing on transnational crime and drug trafficking and climate change as well as other issues. Meanwhile, President Biden’s defense budgets remain relatively flat. Military efforts have been upgraded in Europe, not Asia, as a response to Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Why no pivot?

Despite the threat of a rising China, through four very different administrations from both major political parties, the global balance of U.S. military presence has not shifted. The leadership of neither political party has embraced the concept of a strategic reorientation. Several factors account for this.

Allies

The U.S. has powerful and influential allies and enduring collective security partnerships in Europe, the Middle East, and the Indo-Pacific. All these regions actively compete for American engagement. Washington has a vital strategic interest in the security and stability of all three regions. In each case, these allies have insufficient capacity to ensure regional stability on their own. Each region also includes hostile powers with significant disruptive capability – China, Iran, North Korea and Russia. Thus, the U.S. has found it difficult to move away from any of these regions.

Force structure

The world is not a blank map. The territories available for bases vary greatly in their geographic features and are not mutually interchangeable among the three regions. The Indo-Pacific remains a primarily maritime theater for the U.S., while Europe requires a significant mix of ground and air forces, and the Middle East requires a significant air force presence. The locations where U.S. forces can be based in all three areas are limited.

Also by James Jay Carafano:

Is America AWOL in North Africa?

Culture wars and real wars in U.S. foreign policy

Beijing

While the Chinese regime’s military influence is primarily regional, its strategic arms capability is growing, and its economic, diplomatic, intelligence, cyber and political influence is global. Pivoting to and concentrating on the Indo-Pacific theater alone would not suffice to contain or restrain China.

Further, the results of the recent Chinese Communist Party congress and the consolidation of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s power suggest that Beijing will continue to vie for global influence in parallel to its conventional and strategic arms buildup. This strategy makes a U.S. pivot a less practical response to Chinese activity.

Politics

There is no strong domestic political constituency for a dramatic pivot. While concern over the rise of China is widespread and bipartisan, how to respond to the challenge is not. None of the prominent persons suggested as presidential candidates in 2024 have made the “pivot” a central part of their public views on foreign policy and national security. Recent Congressional action has seen bipartisan support for increased defense spending and new Indo-Pacific initiatives, including support for Taiwan, but not for an explicit shift to Asia.

Economy

While many argue the U.S. pivot should include a strong economic dimension, there is scant bipartisan consensus in Washington on trade policy. A new Trans-Pacific Partnership is extremely unlikely. The U.S. may well introduce some multilateral or bilateral partnership and business initiatives, potentially including a free trade agreement with Taiwan, but the likelihood of a large-scale regional economic initiative is low.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is continuity. The U.S. will maintain a balanced global portfolio rather than drastically reduce its footprint in other theaters to increase its presence in the Indo-Pacific.

There are significant wild cards. One is the U.S. effort to balance demands for more defense investments with rising debt, slowing growth and persistent inflation.

A second issue to watch is the U.S.-China competition over Taiwan. An independent Taiwan remains a vital interest, and it is likely that if Washington anticipated military action by China, the U.S. would rapidly shift most of its military assets to the Pacific. This is especially likely in the near term since Russia has degraded much of its conventional capability in the war against Ukraine and will require time to rebuild its forces.