FATCA’s dragnet tax compliance has high costs

The U.S. remains one of a few countries that claim rights on taxation of labor income earned abroad. Doing so has likely not raised net revenue, as costs outstrip even the rosiest revenue projections. Maintaining the system is detrimental to the U.S. economy and global connectedness and makes international banking and trade more costly.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. forces its citizens living abroad to file and pay taxes to the IRS

- The costs for citizens to comply are high and the whole exercise brings the U.S. little benefit

- In the long run, the policy could damage the American economy

The worldwide structure of the United States’ personal income tax and congressional efforts to enforce it have caused hardship for U.S. expatriates, and it is likely to get worse before it gets better.

Before the 2017 tax reform, the U.S. was one of only six member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that still attempted to tax the foreign-earned income of U.S.-headquartered businesses and citizens. Tax reform began to fix this problem for businesses, by moving toward a “territorial” system that does not claim full taxing rights to business income earned overseas. Foreign resident U.S. citizens, however, were entirely left out of these reforms.

The U.S. remains one of just a few countries that claims taxing rights on labor income earned abroad. Americans living overseas must file income taxes and pay U.S. tax on income earned over the $103,900 exclusion and relevant foreign tax credits for taxes paid to other countries. While filing U.S. income taxes even when no tax is owed may be annoying, Washington’s campaign to crack down on a few high-income individuals hiding their income overseas is backfiring on middle-class expatriates’ livelihoods.

The system of worldwide taxation and accompanying global financial reporting hurts the American economy and makes it much harder for Americans to live overseas.

Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act

The newest enforcement tool for the worldwide tax system was signed into law in 2010 and went into force in 2015. The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is intended to catch tax cheats by making it harder for Americans to keep money overseas and out of the reach of tax collectors at the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The law requires foreign financial institutions, such as banks, to identify and report to the U.S. most types of transactions for all American clients.

Many foreign banks no longer provide financial services of any type to American citizens.

The information reporting regulations are enforced by the threat of applying a 30 percent withholding tax on revenues generated in the United States by the noncompliant foreign financial institution. The U.S.-imposed reporting burdens and withholding penalties faced by foreign banks trying to comply with FATCA regulations have resulted in many foreign banks no longer providing financial services of any type to American citizens.

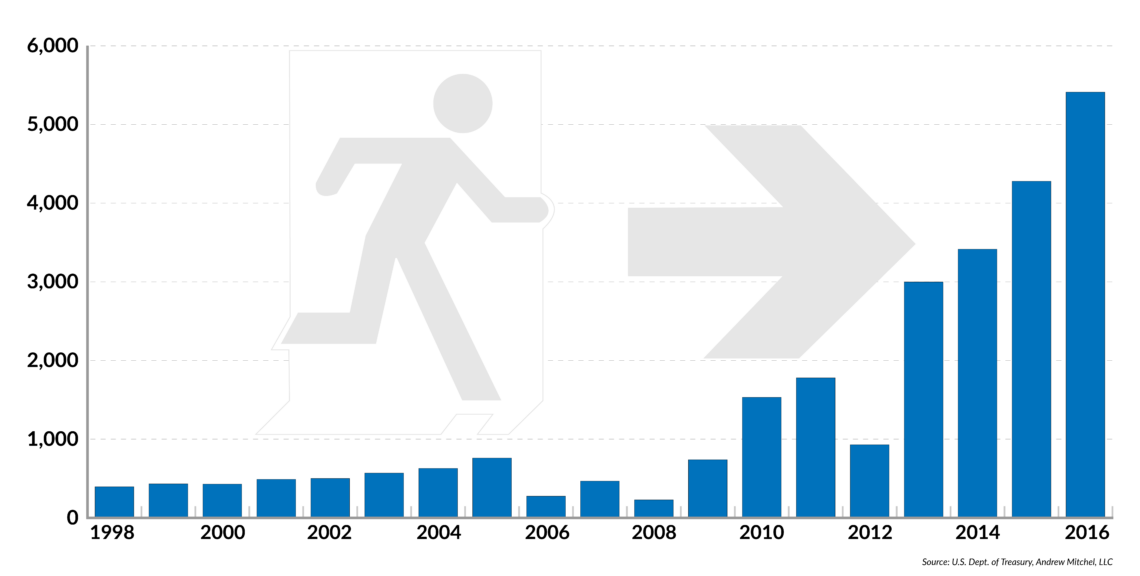

In many cases, it is easier for Americans to renounce their citizenship than to find a bank that is willing to bear the bureaucratic costs and liability of complying with the law. Between 2011 and 2016, the number of U.S. citizenship renunciations increased by 178 percent. The largest single-year increase followed directly after the implementation of FATCA.

The sweeping nature of the underlying worldwide tax system and the draconian enforcement means that these penalties and reporting costs are not only hitting wealthy tax dodgers. The cost of complying with the law hits every American living overseas, not just those targeted by the original legislation. Middle-class Americans living abroad who are fully compliant with U.S. tax laws have lost their mortgages, been cut off from business and personal banking services, and their retirement savings exposed to devastating new tax burdens because their international bank cannot afford the U.S. regulatory burden.

All cost, no gain

In 2010, Congress used FATCA’s projected revenue to pay for temporary domestic business tax credits and employment subsidies. The law and revenue score was primarily a budget gimmick to increase domestic spending.

Since going into effect, FATCA has likely not raised net revenue, and the cost of implementing and complying with the law outstrips even the rosiest revenue projections. A legal challenge to the law in 2015 estimated the compliance costs to financial institutions alone was on track to total more than the optimistic $8.7 billion 10-year revenue estimate.

A recent U.S. government review of foreign asset reporting requirements found that close to 75 percent of foreign account holders had to report separately to the IRS and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). They found that the duplicative systems create “confusion, potentially resulting in inaccurate or unnecessary reporting.” For individuals, confusion and even non-willful inaccuracies can be costly. Mistakes or noncompliance can carry FinCEN penalties that go as high as $13,000.

The government report also found that after five years, the FATCA reporting regime has not yet yielded data that is useful for tax compliance work. The taxpayer identification information reported by foreign financial institutions is often incomplete or inaccurate, making it difficult to match the data to U.S. taxpayers. Like the duplicative reporting system for individuals, financial institutions also must comply with a parallel set of reporting requirements under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard.

Each of these overlapping, but subtly different, reporting requirements primarily works to ensnare unsuspecting taxpayers. The U.S.-citizenship-based worldwide tax system exacerbates the reporting requirements because they are different than in any other country and require compliance from the most marginally attached Americans. The dragnet approach to tax compliance entraps citizens who have lived abroad most of their lives and residents of the U.S. who have an offshore account, interests in offshore trusts, or simple signature power with no beneficial interest.

Maintaining the worldwide tax and reporting system is costly to the U.S. economy and global connectedness. As U.S. persons renounce their citizenship or recoil from foreign financial ties, the U.S. slowly loses potential partners in commercial trade, diplomatic relations and other forms of cultural enrichment. The direct costs of regulatory barriers are high, and the unseen costs to culture and trade are probably even higher.

The worst is ahead

In the never-ending pursuit of new and expanded sources of revenue, governments around the world are implementing ever more intrusive and duplicative tax systems and information sharing regimes. With each new system, the associated reporting and compliance costs fall on taxpayers in the U.S. and around the world, making international banking and trade more costly.

Automatic information sharing largely ends financial privacy.

FATCA accelerated this trend by spawning the OECD’s similar Common Reporting Standard (CRS), which is a global FATCA-like regime. The organization is also working to amend its Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters to increase bulk international tax information sharing.

The U.S. has not fully implemented the amending protocol, but it would mandate that the Internal Revenue Service automatically share bulk taxpayer information with governments worldwide, many of which are corrupt and hostile to Western countries. Automatic information sharing largely ends financial privacy by putting private financial information about assets in every country at risk of being used by foreign governments for expropriation or accessed inappropriately in the all-too-frequent data breaches.

Information reporting and sharing was only the first opening salvo in the FATCA-spawned global tax games. As countries realize that dragnet tax reporting and enforcement does not raise the desired revenue, they will continue to turn to new tax bases and new reporting requirements. New taxes on digital services, advertising, and online users is the next frontier.

A unified global tax compliance regime or new unified taxes on the digital economy will likely remain elusive. Countries will continue to implement new tax initiatives as past and existing projects continue not to raise the expected revenue. Each new effort will layer additional costs on taxpayers and incrementally lessens financial privacy.

The U.S. Congress could relieve some of the burden by moving to a territorial or residence-based tax system for individuals. Existing reporting systems could be streamlined and the IRS could stop sharing bulk taxpayer information without probable cause. However, U.S. legislators are just as keen as their European counterparts to squeeze every last dollar out of taxpayers without concern for the costs. Until budgets are balanced, international tax reforms will likely not lessen the tax burden of businesses or individuals.

Everyday citizens will bear the brunt of the economic and social costs from the increasingly burdensome international financial tax systems.