Wagner and the long history of private armies

The Russians have not invented private military force. Sovereigns over centuries found reasons to pay mercenaries and fear them too.

Officially called Wagner Private Military Company (PMC), the group has made many headlines. Headed by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a longtime member of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, it began as a state-funded but privately-run mercenary organization with access to Russian Defence Ministry training facilities and arms. Reportedly inspired by the private military contractor Blackwater extensively used by the Americans in Iraq, Wagner personnel were initially selected from the veterans of Russia’s most elite military units. More recently, it absorbed thousands of criminals recruited in prisons.

The group debuted during Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea and the violent Donbas secession. Its record in the field was mixed. Since, Wagner has been active in Africa, also with varying effects for the sponsors, but earning money and lucrative commercial concessions from governments that looked for presumably a loyal – because paid for – private military force. Its units went to Syria after Moscow backed its besieged president in 2015 and later to Libya, the Central African Republic, Mali and Mozambique (and, in smaller numbers, other countries). However, Mr. Prigozhin’s force saw its most notable expansion in strength and military role during the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Wagner insubordination?

Close as Mr. Prigozhin was to the Kremlin, there was always an acrimonious tension between Wagner and the regular Russian military. Last June, to everyone’s surprise, Wagner fighters left the front in Ukraine, formed an armored column and began rolling briskly toward Moscow. Whether it was an attempted coup, a mere show or something else, Mr. Prigozhin’s self-described “march for justice” stopped short of the capital. The reason remains unclear. In any case, the tension dissipated after Alexander Lukashenko, the Kremlin-dependent ruler of Belarus, somehow “mediated” – unclear between which parties – and invited Mr. Prigozhin and Wagner into his country.

Read more on Russia-Belarus relationship

Lukashenko’s Belarus in Russia’s embrace

Miraculously, its leadership seems to have a good rapport with the Kremlin again. These days, Wagner men are in camps near the Lithuanian, Polish and Ukrainian borders, which can be seen as a novel threat to Belarus’ NATO neighbors.

Nothing new under the sun

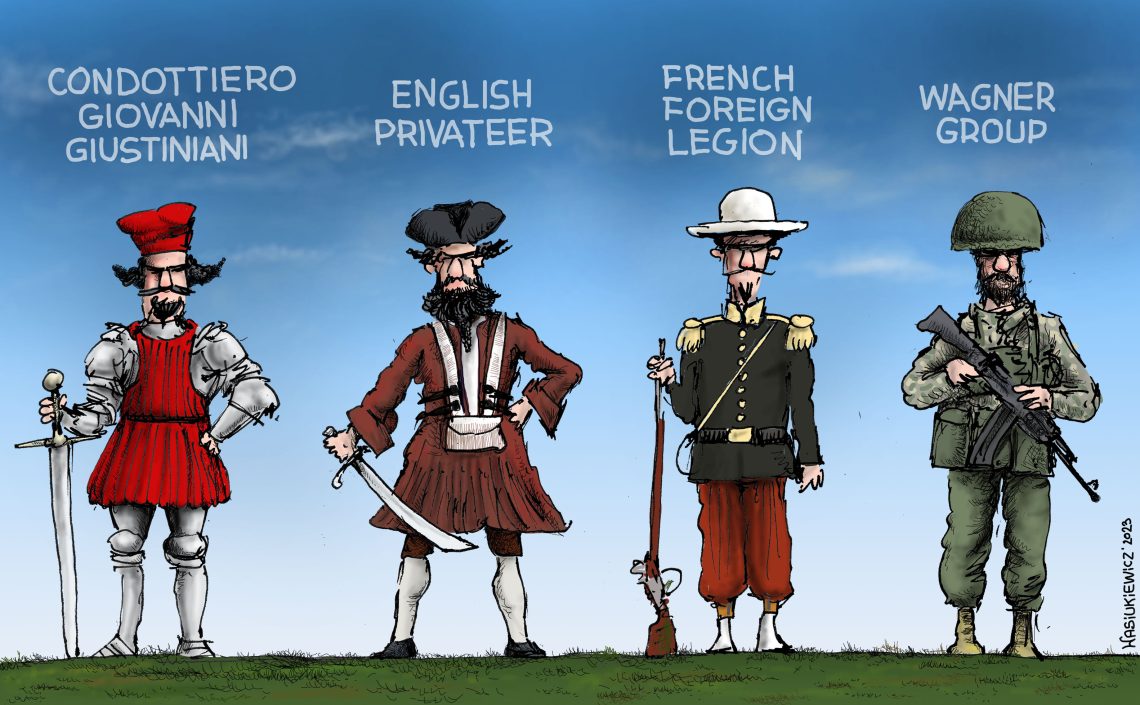

Historically, however, using irregulars and private armies is nihil novi. Sovereigns for centuries recruited knights or private regiments, paramilitary organizations, or, closer to our time, so-called “security companies” to do their bidding.

Soldiers of fortune can form special-use troops, like the French Foreign Legion, created in 1831 to bring foreign nationals into the French Army. Ever since, the Legion has attracted adventurers from all corners of the globe by offering good pay, legal immunity and the thrill of fight and comradeship. The Legionnaires find these in abundance, as North Africa and the Sahel area were in constant turmoil during the 100 years of French colonization and remain volatile today.

The case of Genoa-born nobleman soldier of fortune Giovanni Giustiniani provides a much older historical example of a private force in action. He and the 700 recruits in his command earned enduring fame in Christendom as skillful and daring, if ultimately unsuccessful, defenders of Constantinople during its siege in 1453.

The Elizabethan era produced the fascinating topic of British “privateers,” pirates with papers who acted in part like navy soldiers. On London’s commission, these corsairs plundered Spanish ships carrying valuables from the Americas and raided Spanish settlements in the Caribbean, committing murder, rape and robbery. Curiously, England experienced a cultural renaissance at the time, a golden era of its poetry, music and literature with William Shakespeare penning his immortal plays and sonnets. Culture bloomed in a state that sponsored terror abroad, just as the regime in Tehran sponsors terror now.

Mercenaries paid to guard a state’s head can turn dangerous and against their master if unhappy.

The privateer piracy provided strategic advantages for England and filled the royal coffers. Up to the 18th century, war was a business. Private individuals recruited and equipped regiments and sold their services to European powers.

Historically and now, leaders also have used private forces to guard their personal safety and, if needed, defend their power. Some African rulers have relied on Wagner rather than their armies and security apparatus for these services. The Sahel hotspots, particularly, offer the perfect habitat for adventurers. The instability is homemade, but Wagner profits from it independently of Moscow’s geopolitical ambitions.

The other side of the coin

However, mercenaries paid to guard a state’s head can turn dangerous and against their master if unhappy. The Janissaries, an Ottoman elite corps, killed one sultan in 1622 and revolted against another in 1826 after the sovereigns moved to control and, eventually, abolish the force. In ancient Rome, the Pretorian Guard was involved in numerous emperors’ rise and bloody fall. But politicians, too, could order heads of mercenary groups eliminated if they looked to become too powerful.

The risk is high for both sides. It is not a coincidence that Switzerland, which made exporting fighters and guards one of its most successful businesses between the 15th and 18th centuries, prohibits it today. The only exception still allowed for Swiss men is joining the papal guards in the Vatican.

From that perspective, Wagner is far from a Russian innovation, and its volatility is hardly surprising. But its role depends on the location. In Africa, it is in the mercenary business. It brings money to Russia and those in charge of the group.

Its role in Russia and, lately, Belarus, is harder to assess. Can it be seen as a personal army in the service of Messrs. Putin and Lukashenko? Could Wagner be used for, say, attacking a NATO country while providing a degree of deniability to Minsk and Moscow? Both could maintain that the irregulars slipped out of control: recently, Mr. Lukashenko warned Warsaw that this might happen.

But it is also a perilous game for the two presidents because the mercenaries can become frustrated again and bite the hand that feeds them.

Unfortunately, the Wagner story will continue developing, and we may witness a global rebirth of non-state armed forces. Using them allows sponsors to shirk political responsibility. In an era when the public can watch military conflicts up close through modern media, governments fear the popular reaction to coffins arriving from the battle zone. The rulers want the illusion that the casualties are not “our boys,” and that those maimed and killed are not brothers and sons. This might sound cynical, but war is cynical.