The Wagner Group’s future in Africa

Despite the mercenary organization’s uncertain future in Europe, Wagner’s presence in Africa benefits both the Russian regime and local autocrats.

In a nutshell

- Wagner remains suspiciously active despite Vladimir Putin’s claim it no longer exists

- The Central African Republic shows the contractor’s key role in tapping resources

- African autocrats rely so much on Wagner that the Kremlin may hesitate to rebrand

Weeks after the leader of the Wagner Group, Yevgeny Prigozhin, ordered a putsch against Russia’s corrupt defense ministry, the military contractor remains in limbo. Legally, President Vladimir Putin said Wagner had ceased to exist, while the whereabouts of Mr. Prigozhin himself, who briefly appeared in Belarus in July, after meeting with President Putin in Moscow at the end of June, are unknown.

Yet for a moribund entity, Wagner seems curiously vigorous. As of early July, Wagner was still recruiting personnel across Russia to fight in Ukraine. Its website was still up, while even more strangely, Wagner contracts were still being signed with the Group rather than with the defense ministry, as had been decreed on June 9 in the order that prompted the march on Moscow. Meanwhile, Ukrainian counterintelligence estimated at least 700 Wagner contractors had arrived in Belarus to train the local military and “harass NATO,” raising concerns in Poland that they may organize border incursions by illegal migrants.

Other contradictory signals concerned Wagner’s traditional core operational area – North Africa and the Sahel. On June 30, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov reversed his previous denials of Wagner activities in Africa, stating that “the future of agreements between African countries and the private military company Wagner is primarily up to the governments concerned to decide whether they are interested in continuing this form of cooperation.” Mr. Lavrov confirmed that Wagner operatives would remain in Mali and the Central African Republic as “instructors” to safeguard the security of governments abandoned by their European allies in the face of terrorist threats.

In response to these statements, Fidele Gouandjika, minister and special advisor to Central African President Faustin-Archange Touadera, said that Moscow had subcontracted to Wagner and that its military would remain there, with no major changes. After all, they may replace their leader, “but Wagner’s soldiers will continue to operate on behalf of Russia,” Mr. Gouandjika said.

No signs of leaving Africa

The foregoing suggests radically different outlooks for the future of the Wagner Group depending on which operational chessboard is being discussed. What happens in Africa may be quite distinct from developments in Ukraine or even Belarus. Indeed, the group’s organization itself appears to make a substantial distinction between these operations in Russia’s “near abroad” and other “out-of-area” missions that take Wagner all over the Middle East and Africa.

Facts & figures

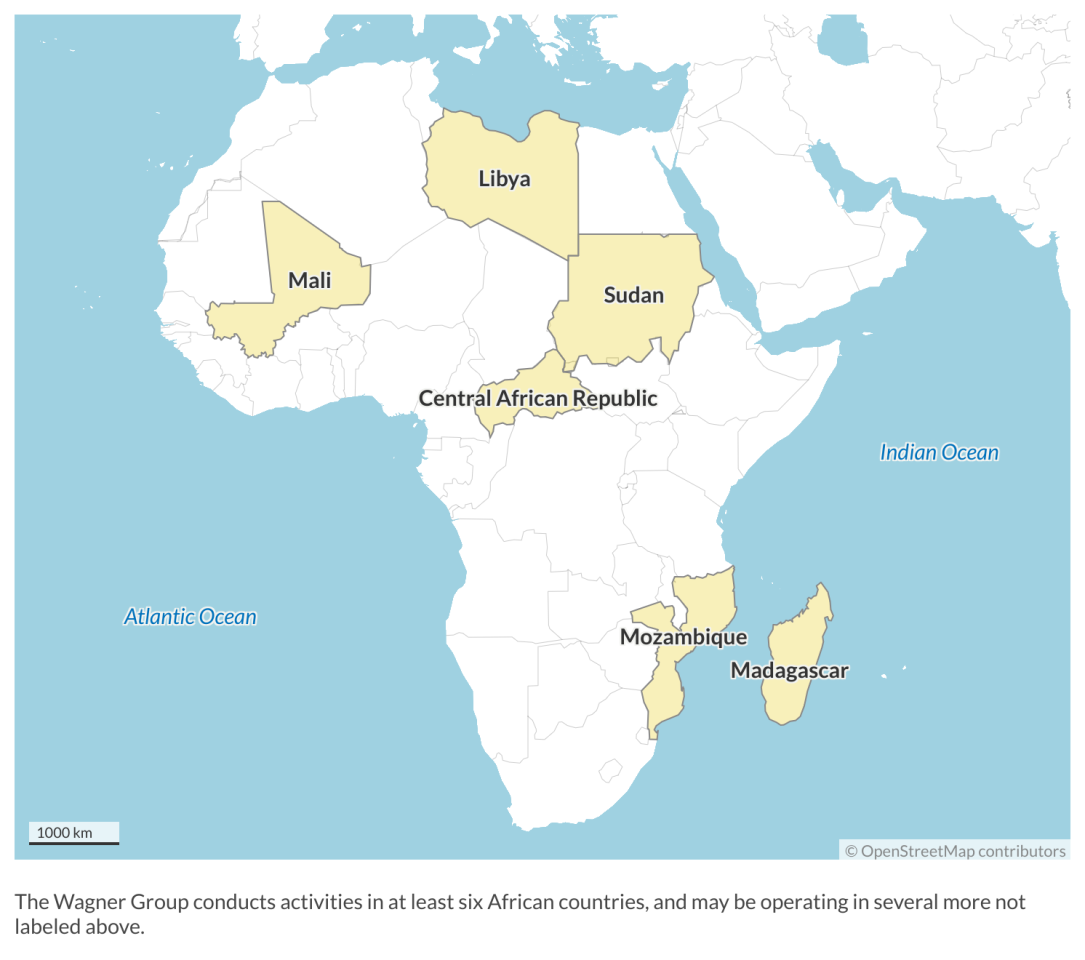

First, it must be stressed that recent months have brought no evidence the Wagner Group has left Africa or plans to do so anytime soon. The group is currently thought to have about 5,000 personnel scattered across the continent. Mr. Lavrov’s words in this context make Moscow’s intentions crystal clear. Wagner’s operations have been a key focus of the Russian presence on the continent since the 1990s, and as such are too important for the Kremlin to abandon. Not only do they strengthen the regimes of certain African states, “stabilizing” them artificially through the judicious application of force, but they are also crucial in priming the pump for Russian arms sales to the continent, while boosting its other key exports in food, metals and hydrocarbons.

Testimony to this complex web of mercantile interests is provided by the various companies associated with the Wagner Group, including M Invest, Sewa Security Services (Sewa) and Bois Rouge (allegedly involved in illicit logging in the Central African Republic, or CAR), along with numerous other entities established to help evade Western sanctions. According to some estimates, in the mining industry alone, these companies generated $250 million between 2018 and 2021.

Needless to say, Wagner’s commercial units operate cynically, with no regard for the physical or economic welfare of local people. Without protection from the company’s military arm, they could not survive long in the African context. That underlines the Wagner Group’s importance on the continent’s wider operational chessboard.

More on the Wagner Group

The Wagner march on Moscow offers another Russian enigma

Russia’s strategy for Africa

The Central African Republic example

For more than a 40-year stretch from the mid-1970s, Russia was not a major player in the CAR, leaving a clear field to France and, to a lesser extent, the United States. Facing a deteriorating political and security situation that morphed into a full-blown humanitarian crisis, France organized the ill-fated Sangaris military mission (2013-2016), which failed to bring about any kind of stability. As the French contingent withdrew, followed by the pullout of U.S. special forces in 2017, local militias took control of the country’s rich natural resources, which include gold, uranium, oil, diamonds and timber. Such was the vacuum into which Wagner moved.

In 2017, President Touadera, dissatisfied with the support he had received from France, met with Mr. Lavrov in Sochi and asked for help rebuilding the national army. A year later, having asked the United Nations Security Council to waive an arms embargo in place since 2017, Russia dispatched Wagner to the country with about 2,000 men and a cargo ship loaded with weapons. The group had multiple functions: instructing the gendarmerie and local security forces; transporting materials to and from Sudan; and acting as national security advisors and personal bodyguards to the president.

Added to this already broad portfolio was the protection of diamond and precious metals mining through subsidiaries such as Lobaye Invest, along with counterinsurgency operations in strategic areas. By February 2019, Mr. Prigozhin was acting as a sponsor of the Khartoum Accord, which saw President Touadera agree with a large group of militias to the apparent goal of restoring order in the country.

In reality, Mr. Prigozhin’s business objectives were multifaceted, as he helped secure Mr. Touadera’s reelection in 2020 while at the same time lending support to local armed groups that allowed him to exploit natural resources. A key figure in running this arrangement was Valery Zakharov, a Wagner employee and former member of Russia’s FSB security service, who has been President Touadera’s national security advisor since 2016.

In January 2023, in an effort to curb continuing human rights violations in Russian-controlled areas of the CAR, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) announced heavy sanctions against Wagner, which it defined as a “transnational criminal organization,” along with Mr. Zakharov, seven other individuals and 16 entities linked to the group.

Scenarios

The CAR is a useful case study to better understand how Russia articulates its ties with African countries, with the Wagner Group’s presence simply one of many pressure points applied by the Kremlin. While the tactics vary by country – Mali and Libya are two good alternative examples – the goal is always the same: influence local governments (or power holders) to obtain business deals and access to natural resources, strategic locations and trade corridors.

Given that overriding Kremlin objective, it is possible to foresee Wagner’s role evolving in one of two ways.

First would be the Group’s withdrawal from Africa, mirroring its pullout from Ukraine. This scenario must be considered highly improbable, although a less drastic “rebranding” variant cannot be ruled out. The main reason is that Russia’s African clients have become so dependent on their contractor-bodyguards that they would find it difficult to survive without them, especially if forced to depend exclusively on their poorly trained armies.

The presence of an instrument of control and repression such as the Wagner Group is indispensable to these African autocrats, who would otherwise face uncontrollable armed rebellions or – perhaps even worse from their point of view – Western-backed democratization movements. Put simply, if Mr. Putin is right that the Wagner Group does not exist, he would have to invent one.

The more likely outcome is that Wagner’s dense network in Africa, from which Mr. Putin has reaped such hefty strategic and financial dividends, will be allowed to remain in place. That might even apply to Mr. Prigozhin and his own web of personal connections. Over the years, Wagner has supplanted most other military contractors while diversifying (on Kremlin instructions) into the economic and political spheres. It would be unthinkable for President Putin to risk losing his grip on these African assets, especially at a time when Russia is experiencing profound international isolation.

Europe’s absence from the African security picture is another strategic advantage the Kremlin is unlikely to let slip away – especially given the strategic leverage afforded to Moscow by the twin threats of illegal migration and Islamic terrorism. Instead, Russia is much more likely to double down by increasing its military footprint, possibly with instructors drawn directly from the armed forces. That could well be the Russian defense ministry’s preferred scenario, but for now must be considered less likely than sticking with the tried-and-tested option: Wagner.