Mali’s struggle for stability

The French intervention in Mali successfully tackled the spread of terrorism in certain areas, but without government efforts to address extreme poverty, these gains were short-lived.

In a nutshell

- Mali’s urban south contrasts with its troubled and sparsely populated north

- Frustration with the French intervention led Malians to seek assistance from Russia

- France needs to reevaluate its cooperation strategies with former colonies

Mali is a geographically divided country. The south is composed of agricultural land with a population density of 70 inhabitants per square kilometer. Bamako, the political and economic capital of Mali, and most of the country’s infrastructure, is located in this highly urbanized area.

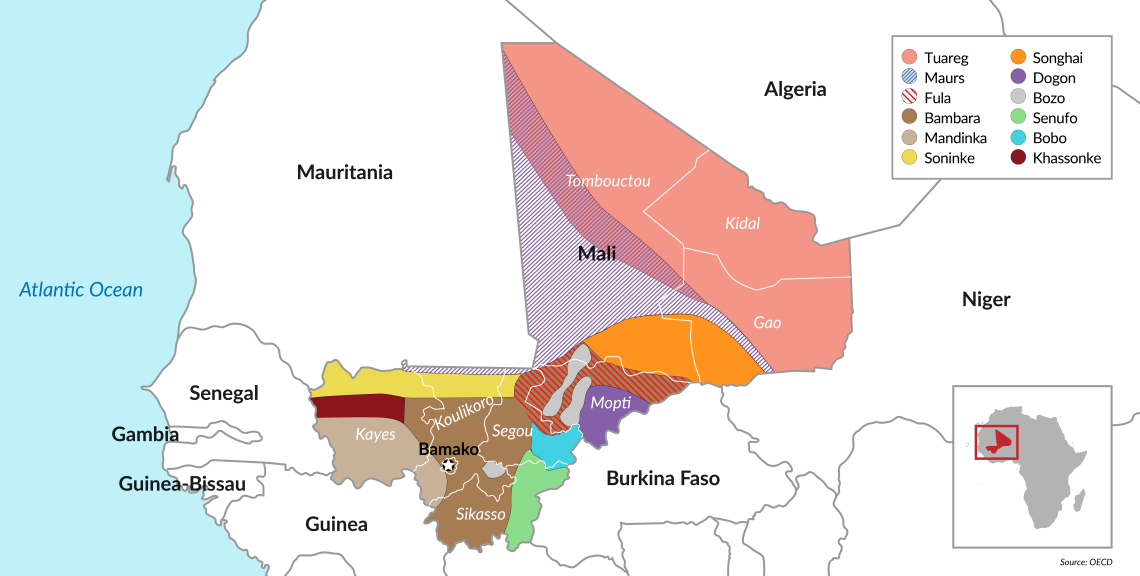

In contrast, the north of the country is a vast and sparsely populated territory where the Sahel and the Sahara meet, home to several nomadic groups. The territory accounts for two-thirds of Mali. Tuaregs, who claim autonomy there, call the region Azawad. This area has been a site of political tension since the 1960s and has proved a breeding ground for terrorist, jihadist and separatist groups.

Some of these movements were supported by Algeria. Others were formed by militiamen who came from Libya after the fall of dictatorial leader Muammar Qaddafi, seeking autonomy for their territory. There are also groups affiliated with al-Qaeda or the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh). These are at the heart of the unrest that continues to plague the country.

Assessing the French intervention

In 2013, the Malian government – faced with jihadist convoys advancing toward Bamako – called on France to intervene. But 10 years later, nothing is resolved. Worse, the Malian rulers who came to power after the coups of 2020 and 2021 accuse France of having done nothing to restore peace. They have turned to Russia and its Wagner Group to fight terrorism and restore order.

The unrest is not abating. Wagner commandos have been systematically looting the country’s mineral resources and are taking part in the trafficking of all kinds: weapons, cigarettes, drugs and even people for illegal immigration.

Drug trafficking is a long-standing issue in Mali. The old drug route from Latin America to Europe via North America has been replaced by a path from Latin America to the Gulf of Guinea. Mali serves as a gateway to Europe, causing lasting insecurity. Traffickers collaborate with terrorist groups who guarantee safe passage in exchange for financing. In northern Mali, traffickers, terrorists and jihadist movements have created a powerful alliance that is beyond the control of the government in Bamako.

Facts & figures

Mali’s main ethnic groups

Failure of the French institutional model

As part of Operation Barkhane (2014-2022), the French army intervened in the north and eliminated terrorism in part of the region. But following these interventions, the Malian state failed to regain a foothold in the pacified areas of the north. Bamako only established a garrison of armed forces but did not make state services available. To this day, the Malian government sticks to this approach and does not allocate sufficient resources for the north. Malian leaders want a united Mali, but they do not take into account the diversity of its regions.

Mali’s institutions were directly modeled after those of the French Republic. They are ill-suited to a country with extremely varied territories and ethnic groups. This is undoubtedly one of the causes of tension between the Malian regions and the central state. Federal or confederal structures and bodies respectful of different traditions would have allowed governance specific to each region.

Ideally, the pacification achieved by French forces would have been followed by local measures against extreme poverty. The French government had wanted the army’s security operations to go hand in hand with development projects in the north, led by France’s development agency. But the authorities came up against a wall of bureaucratic procedures, and aid workers were reluctant to coordinate with the armed forces. As a result, the earmarked funds were used to finance electrification works in southern Mali and the renovation of the sewerage network in Bamako.

The situation in Mali is like that in most former French colonies. After independence, France stayed involved but failed to transform these ties into relations between two sovereign countries. Agreements were concluded under which France aided in most areas: security, culture, education and development. At the same time, political institutions after the French model were being set up.

With the support of France and international institutions, African governments are developing autonomous economic and social development policies. However, many former French colonies are still facing political instability, ethnic tensions and endemic corruption.

As a result, postindependence years have been rocky in most former French colonies. France, which cooperated with the authorities and intervened at their request, is now blamed for this instability. Part of the African youth accuses Paris of not genuinely helping their countries on the road to development.

Today, many of these countries want to renegotiate a development agreement with France. But France is not doing well economically, and cannot compete with China, Turkey, or even Brazil, which offer fully funded projects. Other Western countries like the United States and the United Kingdom are closely involved in the exploitation of mineral resources. Russia is also determined to spread its influence on the African continent and attempts to gain control of raw materials through its Wagner Group.

More on Africa

The lost promise of South Africa

Tunisia’s democratic decline

A new cold war in Africa

A new cooperation strategy

So what can be done to reestablish relations of cooperation and friendship with these countries whose inhabitants are very close to the French? Many families have relatives who emigrated to France and became French nationals.

These countries are fully sovereign; no one can impose institutions on them. Contrary to what some claim, Africa has been making history for a long time, long before the era of European colonization. Empires and kingdoms governed the continent for centuries. African countries are perfectly able to choose governance models on their own, without referring to Western systems.

It was absurd for France to support the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) when it enacted economic sanctions against Mali because the authorities took power following a coup without scheduling elections. Many African countries have rulers whose power is unconstitutional or comes from a military takeover and are still recognized by the international community. The ECOWAS sanctions are considered unfair by many Malians and have made it possible to rally the people behind the authorities.

Western countries must respect human rights, as Pope Francis invited us to do when he proclaimed to the world: “Take your hands out of Africa, stop suffocating Africa: it is not a mine to be exploited or a land to be plundered.”

Modest aims are likely to be more successful than all-encompassing global development aid policies. Western companies and organizations can lend assistance and participate in projects without interfering in national policy.

China and Turkey have successfully developed a footprint in Africa by participating in infrastructure projects and providing substantial funding. By opting for this type of approach, France could avoid the curse of development aid described by Kenyan economist Dambisa Moyo, which encourages corruption and weakens governance.

Finally, if a friendly country in Africa wishes to conclude a military cooperation agreement, France should proceed with care. The French military can protect countries against specific threats, but these interventions must have a clear objective. Otherwise, France will be tempted to agree to the requests of governments that want to maintain this presence indefinitely, essentially turning the intervention into an occupation. This is what happened in Mali.

France is at a crossroads in its relations with Africa. It must have the courage to reinvent its African policy and renounce development “assistance,” opting instead for a policy that favors savings and investment.