Water as a weapon

The destruction of Ukraine’s Kakhovka Dam is only the latest in a tradition of weaponizing water and its massive infrastructure. Conflict over water resources is only set to become more common.

In a nutshell

- Water, essential for life, can have enormous destructive potential

- Chinese water infrastructure projects carry a geostrategic subtext

- Fresh water will see more claims of property rights, driving conflict

In the early hours of June 6, 2023, an explosion ripped through the dam at Nova Kakhovka on the Dnipro River, unleashing a giant flood downstream that inundated over 600 square kilometers of densely inhabited land. More than 40,000 people were affected; agricultural topsoil, together with crops and land mines, was washed into the sea. Fresh water supplies were contaminated by chemicals released from their storage tanks, and outbreaks of cholera followed.

The scale of the disaster fits a pattern of similar dam failures. The destructive power of flooding has been seen in numerous historical accidents, like those of Frejus, France (1959), Tesero, Italy (1984), and Brazil’s Brumandinho mine (2019). Perhaps the greatest (if poorly documented) episode, at China’s Banqiao and Shimantan dams (1975), likely claimed some 150,000 lives. At Nova Kakhovka, however, the failure was not due to natural forces or an engineering miscalculation. This time, it was an act of war.

All evidence points to Russia bearing responsibility. The dam was completely controlled by occupying Russian forces and had been mined to prevent Ukrainian crossings. The explosion seems to have taken place inside the dam. What is still being debated is whether it was a strategic decision made to blunt the force of the looming Ukrainian counteroffensive or simply a result of sloppy neglect.

Dams and reservoirs as targets

The Kakhovka Dam was not the first time that water infrastructure has been attacked as an act of warfare, to exploit the forces of cascading water for the destruction of the infrastructure and industrial assets of an enemy. On May 17, 1943, British bombers attacked six reservoirs inside Nazi Germany. Two dams (Mohne and Eder) were badly damaged, and more than 300 million cubic meters of water rushed down toward the Ruhr area or toward Kassel, respectively. Coal mines were flooded, bridges and roads washed away and about 2,000 people lost their lives (tragically about half of them prisoners of war in forced labor camps). The effect on the German defense industry in the Ruhr area was marginal: it would grow another 50 percent after the incident, reaching its productive zenith in July 1944.

Water reservoirs have also been used with an inverted purpose. In February 2022, Ukraine forces blew up a dam across the Irpin River, successfully stopping Russian infantry from advancing on Kyiv. An entire village was flooded, but Kyiv was saved. Russian forces were simply bogged down in soggy soil. Some 80 years earlier, the Red Army used similar tactics to delay the German Wehrmacht advancing on Moscow.

All over the world, water reservoirs regulate rivers to secure supplies of drinking water and to harness hydraulic energy. Reservoirs do not affect the global climate, although they are not environmentally neutral. Many rivers are well known for their conspicuous dams: the Nile (the Aswan and Grand Renaissance Dams in Egypt and Ethiopia); the Euphrates (the Ataturk Reservoir, with 21 further barrages on the territory of Turkey); the Zambezi (the Cahora Bassa Dam in Mozambique); the Parana (the Itaipu Dam on the border of Brazil and Paraguay); the Yangtze (China’s Three Gorges Dam).

If any of these were to collapse, the damage would be incalculable. In China, for example, the cities of Wuhan, Nanjing and Shanghai would be affected, together with thousands of smaller localities. Russia is home to some of the world’s largest reservoirs (Kuibyshev, Bratsk, Rybinsk and Volgograd), whose dams were built under Josef Stalin. They are old, poorly maintained and vulnerable structures.

Tajikistan is now building the Rogun Dam across the Vakhsh River, high up in the Pamir Mountains. China has control over all six major river systems that drain eastern and southern Asia. It controls the entire stretch of the Huanghe (Yellow River) and the Yangtze, as well as the upper reaches of the other four large rivers – the Lancang (Mekong), Salween, Yarlong Tsangbo (Brahmaputra) and Indus – since all four have their sources on the Tibetan plateau. Three of them pass through gorges up to 2,000 meters deep. These rivers descend from an altitude of over 5,000 meters to less than 2,000 meters on Chinese territory. As they cascade down from their Tibetan heights, they have long been almost inaccessible.

The Chinese government, however, has decided to exploit their enormous energy potential, offering better flooding control to those downstream. Beijing is planning 14 dams across the Salween and another across the Yarlong Tsangbo at the Dehang Canyon (where the river suddenly turns south). The latter would create a gigantic lake extending over 10 kilometers and generating about 40 gigawatts of electricity. It would also provide an opportunity to redirect water upstream toward the arid areas of Tibet.

The ostensible rationale for these projects is that China can regulate the water flow of highly irregular torrents. But there is also a concealed threat: control over these flows gives China’s political (and military) leadership the ability to use them for either beneficial or destructive purposes. Beijing can threaten all four riparian countries along the Mekong River – Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand, members of the Mekong River Commission – with floods capable of washing away swaths of fertile soil and human settlements, or alternatively with restricting water supplies during critical agricultural seasons. A collapse of the future dam across the Brahmaputra would have devastating effects downstream in India’s Arunachal Pradesh and Assam and in Bangladesh.

The western United States is also exposed to water risks because most of the rivers flowing down from the Rocky Mountains form huge reservoirs along the Columbia, the Colorado and the Snake and White Rivers. Three of the largest artificial lakes (Lake Powell, Lake Mead and Lake Mohave) control the flow of the Colorado River. Serious droughts have recently demonstrated that demand for water upstream can conflict with demand downstream.

Modern dams are extremely solid constructions. They cannot be destroyed by terrorists. But modern conventional bombs (like the American GBU43/B or the Russian AWBPM) could cause sufficient damage for the force of the water to accomplish the rest. A nuclear bomb could easily obliterate an entire reservoir. Dams are elements of critical infrastructure and could become targets during a war, as the Kakhovka Dam has shown.

Conflict over usage and access

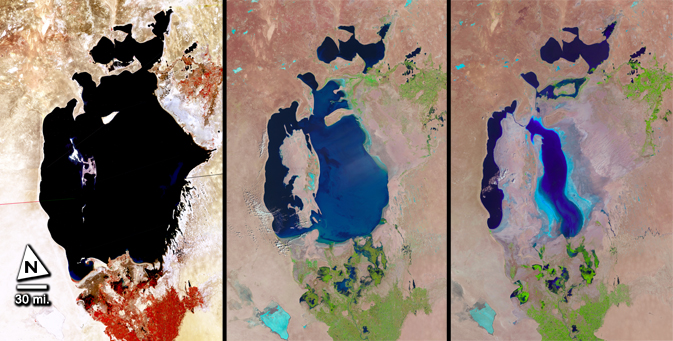

Another dynamic of water conflict is found in areas of irreconcilable usage. The rivers of Amu Darya and Syr Darya illustrate this tension in Central Asia. Their waters are used for energy generation, drinking water, agricultural irrigation, industrial processes and cooling; they are also used as large sewage systems carrying human waste, nitrates, microplastics and pesticides. Those few droplets that still reach what was the Aral Sea are so contaminated they are unfit for human consumption. This vanishing of the water has destroyed a once flourishing fishing industry, while contributing to climate change, desertification and dust storms that scatter toxic sediments across wide distances.

Similar changes are taking place in the Dead Sea, whose water level continues to sink by about one meter each year, increasing its already exceptionally high salination. In the case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Israeli government not only taps heavily into the fresh water of the Sea of Galilee, draining the Jordan River and contributing to the drying up of the Dead Sea; it also tries to secure exclusive access to the underground water veins and lenses that supply Israeli cities with drinking water and its agriculture with much-needed irrigation. Superimpose a map of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and a geological map of underground water tables, and they largely coincide.

Desalination

Desalinating seawater can serve as an alternative source of fresh water, but it requires enormous inputs of energy. To generate one cubic meter of fresh water from seawater, one needs 3 kilowatt-hours of electricity. Transportation from the coast inland adds further costs. Assuming one kilowatt-hour costs around 0.15 euros, that would translate into a price of 0.60-0.80 euros per cubic meter of fresh water – far too much for most consumers in developing countries.

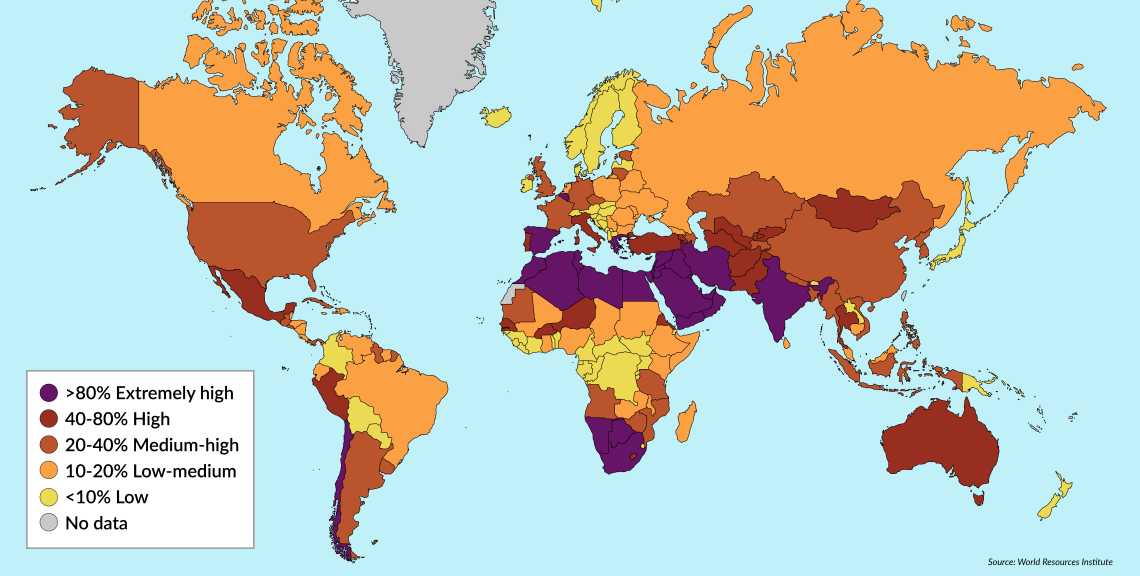

All countries stretching westward from Iran across the Arabian Peninsula and the Sahara Desert to Mauritania are experiencing water stress. Access to and control of scarce water resources will be increasingly contentious in these places. Most of the reserves underneath the Sahara Desert are fossil water, meaning they cannot be naturally replenished once depleted. Of particular importance is protecting these few sources from the contaminating waste of industry, humans, nitrates and pesticides.

Facts & figures

Water stress by country, 2050 estimate

Scenarios

After the degradation of land, the next “tragedy of the commons” could become air and water. Fresh water used to be abundant, therefore nobody claimed property rights or political control. On the contrary, irrigation systems were often the basis for cooperatives and concepts of “just distribution.” With growing demand from cities and industry and the rapid spread of water-intensive crops (like rice or avocados), fresh water is becoming scarce and valuable – a precious commodity that demands protection and therefore political control. As with mineral water, fresh water will face increasing claims of property rights excluding others from access and use. Since many river systems cross political borders, such national property rights are likely to cause tension if not confrontation.

The result will be rivalries, disputes and conflicting interests, both within and among states. Climate change could exacerbate irregularities in precipitation and consequently in the availability of water. This in turn would increase pressure to store water, extend political control over vital sources and even interfere with patterns of precipitation.

If hunger is a rising threat to humanity, the similarly rising threat of thirst should not be underestimated. It might turn out to be even more important, since water has so many diverse usages and remains essential for all life on the planet, with no substitutes.