The WHO may be Covid-19’s next victim

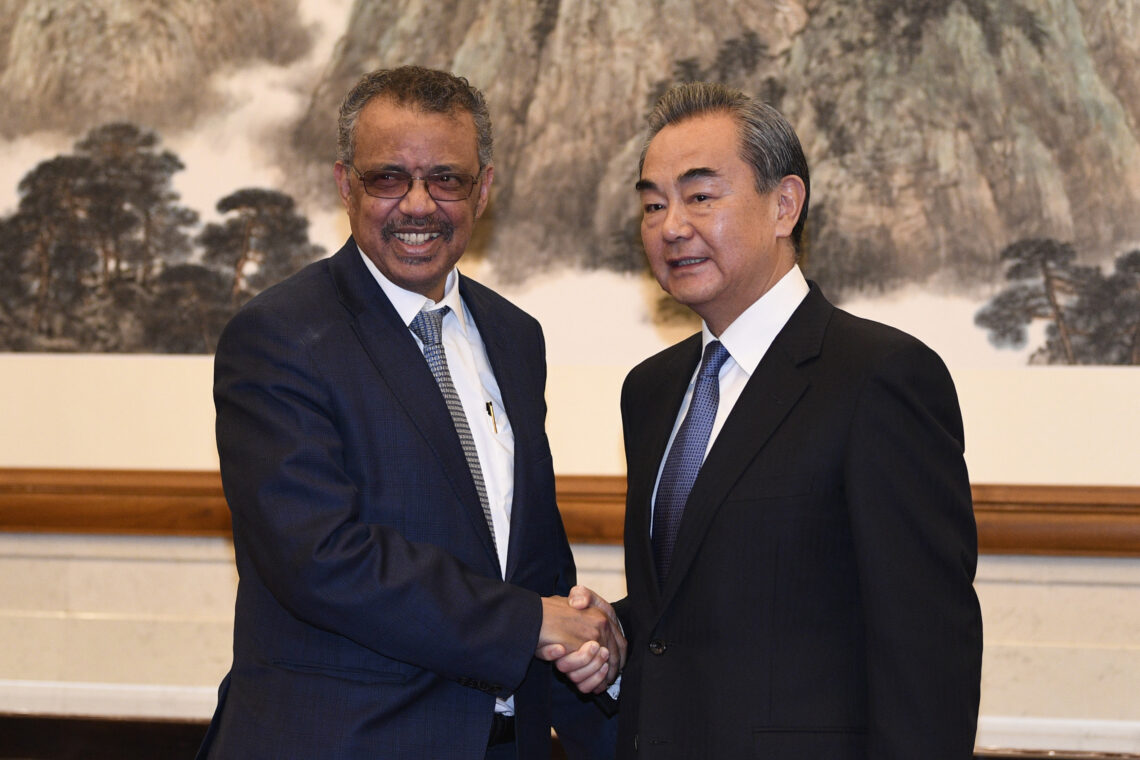

The World Health Organization did poorly in living up to its responsibilities at the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Much of this can be put down to WHO leader Tedros, who seems to be heavily backed by China. The future of the organization depends on the West’s reaction.

In a nutshell

- WHO leader Tedros Adhanom is a controversial figure

- China seems to have strong influence in the organization

- After Covid-19, the West has several options to neutralize the WHO

Covid-19 vaccines are being approved around the world and have even become available in the United Kingdom. More countries will begin inoculating their populations in the coming weeks and months. This is great news, of course. The world’s pharmaceutical companies may yet succeed in ending the nightmare that the coronavirus has caused, and they deserve credit for ensuring that people are protected and can all but resume their normal lives.

Among this good news, we can begin to draw some policy lessons from the pandemic. Two facts are indisputable: Nearly all governments initially underestimated the threat from Covid-19, and most of them failed to develop a consistent strategy once the full implications became apparent.

The World Health Organization (WHO) was in charge of monitoring the pandemic, producing and spreading clear and accurate information, as well as recommending short-term remedies and long-term strategies. It failed on all accounts.

More transparency would have saved thousands of lives and reduced the economic disaster that followed.

To make matters worse, many suspect that WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus knowingly downplayed the scale of the pandemic early on. They believe he attempted to minimize the Chinese government’s responsibility for triggering the disaster and hiding the consequences. More transparency would have saved thousands of lives and reduced the economic disaster that followed.

Controversial leader

The WHO’s failure raises two main questions. How could Dr. Tedros make it to the top and stay there? And does such an organization have a role to play in the future? These are crucial questions, since some countries (including the United States) are tempted to quit the WHO. Many people believe that Dr. Tedros should step down immediately.

His career path is controversial. He is not a medical doctor, having earned a PhD in community health from the University of Nottingham in the UK. He also studied infectious diseases in Ethiopia and the UK. More importantly, he was a prominent member of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, a political party that has engaged in activities some experts have described as terrorism. His academic credentials and political experience contributed to his appointment as health minister of Ethiopia, where his policies have been subject to praise by some, but also to harsh criticism by human rights organizations. Some accuse him of having covered up three waves of cholera while in office.

Dr. Tedros became Ethiopia’s minister of foreign affairs in 2012. During his time in that office, the government was denounced for its frequent use of violence. Nevertheless, in 2017, sustained efforts by the African Union and China helped him land the top job at the WHO.

Facts & figures

Dr. Tedros’s appointment therefore featured a mixed record and a clear geopolitical undercurrent. Many believe that China’s economic ties with countries in Africa played a key role in putting together the majority (133 votes out of 186) that supported his candidacy. Hence, Dr. Tedros’s rise proves two facts. First, the WHO offers China a chance to show its power, strengthen its bonds with its current economic partners and pander to African leaders seeking prestige and visibility on the international scene. Second, Western leaders were sidelined: either they fought and lost, or they simply woke up after the battle was virtually over.

The former is probably closer to the truth. If so, the real question is whether the West could have won the fight, whether it can win future rounds, and whether it should reconsider its strategies or just give up.

Chinese influence

Appointments to top jobs in international organizations often follow some unwritten geopolitical rules. For example, the World Bank president tends to be an American, while a European is the International Monetary Fund’s managing director. WHO leadership could go to a representative of the Chinese bloc. In this light, China’s strategy is clear. Beijing has the economic and political weight to claim such a job for one of its own, but it seems more inclined to cement its influence in other regions rather than act the prima donna and possibly provoke tensions.

The WHO mess has shown the limits of Western opposition and the extent to which such organizations can be manipulated.

Next time, will the Europeans or the Americans pick their own developing world champion? Probably not, because the options are limited. A large share of Africa and Southeast Asia has come under Chinese influence. Beijing might not choose the top international bureaucrats, but it might acquire indirect veto power in the not too distant future.

Scenarios

Many commentators consider Dr. Tedros’s performance unsatisfactory. But that is not the point. The WHO mess has shown the limits of Western opposition and the extent to which an international organization can be manipulated. Dr. Tedros’s term will expire in 2022. The West has about a year to produce a viable strategy to counteract China in the developing world. It will not be easy, and time is running short. Yet, there are three alternative scenarios.

Collusion

One scenario amounts to collusion. At the moment, the role of international organizations is relatively modest and declining. Key decisions are usually made by a handful of countries that subsequently present their agreements to the global public by means of a transnational intermediary. By doing so, their policies acquire a veneer of technical impartiality. Opponents find it more difficult to attack an international body recognized and funded by nearly 200 nations than to target a single country.

In most cases, a lack of agreement among the leading countries brings stalemate. This is what we have observed in recent decades. Yet, things could change in the future, especially in cases where global solutions are allegedly required, on issues like climate change, pandemics and international fiscal harmonization.

If that is the game that the West wants to play (a big if), then the only viable strategy is collusion with China. Europe is probably willing to examine this option, although its internal tensions limit its ability to reform the global geopolitical and economic architecture. Under such reforms, the WHO could become a significant actor. In the U.S., it is not clear what the Biden administration will do.

Parallel organization

Another scenario would see the West withdraw from the WHO and possibly set up a parallel organization. This is what President Donald Trump announced he was planning to do, much to the dismay of the secretary-general of the United Nations (the WHO is a UN agency). President-elect Joe Biden has promised not to go down this path. Perhaps his reasoning is that keeping the U.S. in the WHO can do no harm since the organization is discredited (something that the Chinese had failed to anticipate).

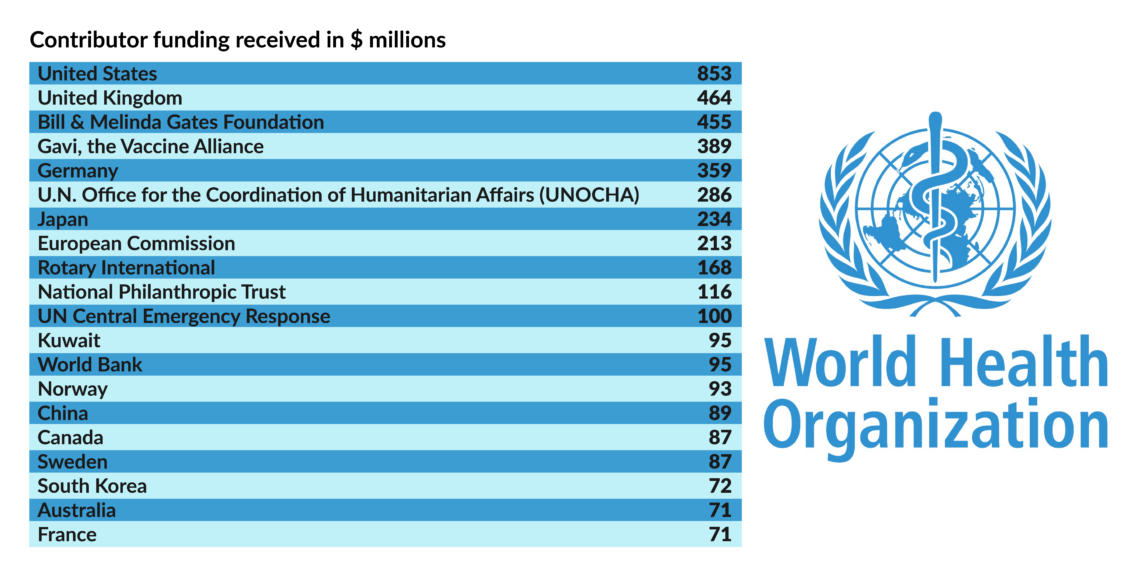

True, the U.S.’s annual membership fee is not negligible, since its yearly compulsory contribution amounts to some $120 million and its voluntary contribution equals some $330 million. Yet, starting and funding a new organization would be risky, possibly useless, and expensive. It would be politically risky, since nobody really knows how many countries would leave an ineffective WHO with a well-known governance to join a new body steered by the U.S. It would be useless, unless Washington were to set out a clear mission for the new organization. It would be expensive, since the U.S. would probably be expected to fund its creation.

Abandon ship

The third scenario would be for the U.S. and its Western partners to abandon the WHO and forget about having a world agency devoted to health. After all, inadequate health systems result from poverty – and there is certainly no lack of governmental, nongovernmental and international organizations fighting poverty. Although this would make a lot of economic sense, quitting an international organization may become a rather delicate matter of foreign policy. Small countries want to have a seat wherever they can enjoy the illusion of being (minor) players in big games. Large countries fear that their quitting might be resented by the world community and attract criticism.

It is therefore unlikely that the WHO will disappear. China will probably use it to promote its image and extend its influence, while the West will strive to make it irrelevant: a compromise solution that will spare policymakers some trouble but cost taxpayers around the world some $3 billion a year.