Scenarios for vaccine diplomacy in Africa

On the African continent, there are multiple geographical and economic challenges in the fight against Covid-19. Through “vaccine diplomacy,” countries like China, Russia and India hope to bolster their influence in Africa – but their efforts can only go so far.

In a nutshell

- Countries around the world seek to influence Africa via vaccine diplomacy

- No single actor currently has the upper hand - but China is the most visible player

- A diverse array of strategies is needed to meet the rapidly changing circumstances

With the development of vaccines for Covid-19, the battle against the pandemic has entered a new phase. Some countries, including many in Africa, face obstacles obtaining and distributing them. Others are jealously guarding their supplies. “Vaccine nationalism” – where countries push to get first access – has become a challenge to overcoming the disease.

That does not mean that a globalist approach is necessarily better. The road toward immunization will likely require diverse solutions at the national, regional and global levels. Rapidly evolving circumstances will demand flexibility from governments, organizations and officials.

Globalism vs. vaccine nationalism

The main instrument to ensure equitable vaccine distribution worldwide is the Access to Covid-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, a partnership launched by the World Health Organization (WHO). Within the ACT Accelerator, Covax is the body in charge of vaccination and has set the ambitious goal of delivering 1.3 billion vaccine doses to 92 low- and middle-income countries in 2021.

Global programs are not the only, or even the best, solution for guaranteeing that vaccines are universally available.

While Covax has missed its first goal of guaranteeing that poor and rich countries start their vaccination programs at the same time, the G7’s virtual summit in February 2021 gave new momentum to the initiative. President Joe Biden pledged $4 billion from the United States. Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised the United Kingdom would donate surplus vaccines to poor countries. The European Union announced that it would double its initial contribution, for a total of 1 billion euros, and said it would pay particular attention to vaccination in Africa. Germany pledged an additional 900 million euros and French President Emmanuel Macron has called on rich countries to send between 3 and 5 percent of their vaccine supplies to Africa.

International cooperation has proven vital in discovering, producing and distributing vaccines. However, global programs often involve a multitude of actors, set unrealistic goals and have highly bureaucratic, inefficient processes. They are not the only, or even the best, solution for guaranteeing that vaccines are universally available.

Availability, access, distribution

The various vaccination strategies that countries take, as well as outside powers’ vaccine diplomacy, will have a range of effects on the outlook for health and economics in Africa, not to mention its geopolitics.

According to the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), vaccinating 60 percent of the African population will require at least 1.5 billion doses. With the current limits on availability, access and distribution, the challenge ahead is substantial.

Facts & figures

Covax has delivered more than 60 million vaccine doses to 31 African countries so far. The aim is to send 600 million doses by the end of the year. Beyond Covax, African countries are betting on regional and bilateral arrangements. The African Union, through its Africa Vaccine Acquisition Task Team (AVATT), has secured 670 million doses of vaccines, to be distributed in 2021 and 2022. Recipient countries are expected to secure financing with support from the African Export-Import Bank, which will advance procurement guarantees to manufacturers. The initiative is crucial because it increases African countries’ control over the process.

Besides the difficulties surrounding availability and access, there are significant obstacles to distributing vaccines. A November 2020 analysis by the WHO, based on countries’ self-reporting, scored the continent’s readiness to roll out the vaccine at just 33 percent, well below the desired benchmark of 80 percent.

In urban areas, population density is especially high and large numbers of people live in informal, often unmapped settlements. On the other hand, the continent’s rural, low population density areas are often difficult to reach due to adverse geographic and logistic conditions, including lack of adequate transportation infrastructure and storage facilities.

Trying to distribute mRNA-based vaccines in these areas would be particularly challenging. They must be stored in ultra-cold freezers, which are expensive and extremely scarce in Africa.

China’s vaccine diplomacy

Having notched foreign policy successes with its “mask diplomacy” strategy early in the pandemic, Beijing is now shifting to vaccine diplomacy – and China may be in a better position than other powers to match African needs. This vaccine diplomacy should be understood both in light of China’s Health Silk Road strategy, and its national recovery plan, which focuses on increasing internal economic strength and self-sufficiency through participation in global trade.

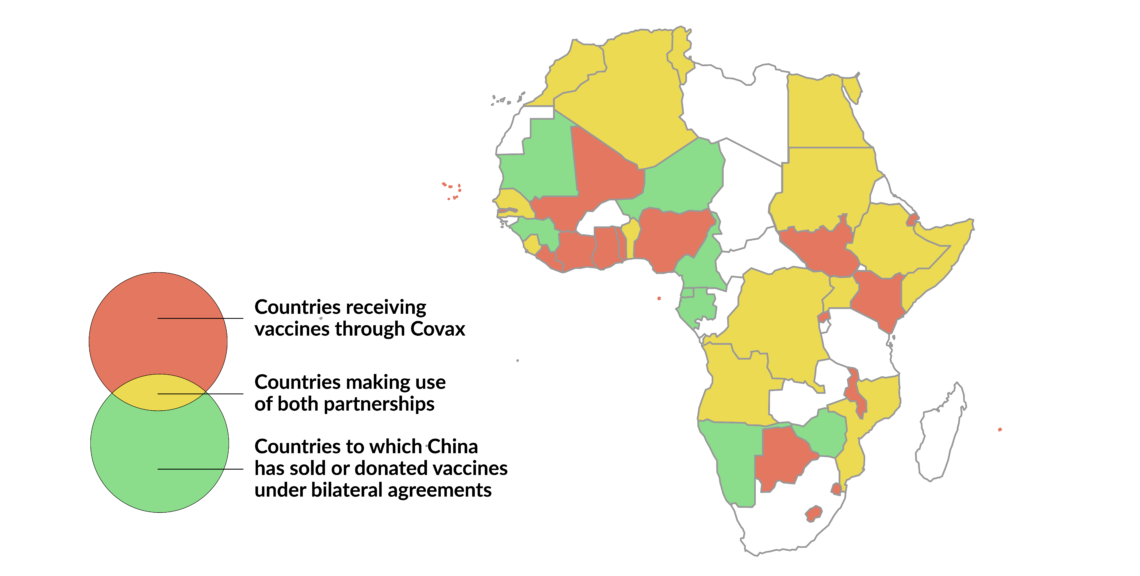

Beijing has committed to provide vaccines to 25 African countries, and has delivered them to 22 so far.

Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy relies on a combination of global and bilateral approaches. And despite promises to share its vaccines with the world, China only joined Covax in October, three weeks after the deadline set by the initiative. The Trump administration’s refusal to step in, combined with fears of increasing criticism, likely helped convince Beijing to join the initiative with a pledge of 10 million vaccine doses.

China is also pursuing bilateral arrangements with countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Latin America. For now, there are five Chinese-developed vaccines:

- Two vaccines (WIBP-CorV and BBIBP-CorV) based on an inactivated form of the virus and produced by the national pharmaceutical firm Sinopharm

- CoronaVac, also inactivated and developed by Sinovac Biotech;

- Convidecia (Ad5-nCoV), a single-dose viral vector-based vaccine developed by CanSino Biologics

- RBD-Dimer, a more recently developed protein subunit vaccine by Anhui Zhifei Longcom in partnership with the Chinese Academy of Sciences

Facts & figures

Types of vaccines

- Inactivated vaccines consist of pathogens that have been grown and then killed to destroy disease producing capacity. The dead pathogens are then introduced into the body to provoke an immune response.

- Viral vector-based vaccines introduce a modified virus (the vector) that directs the body’s own cells to produce parts of the pathogen that provoke an immune response.

- Protein subunit vaccines introduce a protein from the pathogen.

Beijing has committed to provide vaccines to 25 African countries and has delivered them to 22 so far, in addition to other developing states around the world. Indonesia and Turkey, for example, have ordered 125 and 50 million doses of Coronavac, respectively.

China’s vaccine advantages

When it comes to increasing its global projection through vaccine diplomacy, China benefits from concrete advantages. The first is political. Whereas the EU and U.S. are preoccupied with internal problems, China’s apparent success in tackling the pandemic puts it in a position to engage in an ambitious geopolitical strategy. Unlike the EU or the U.S., Beijing has been able to strengthen diplomatic ties with countries across Africa over the last year.

The second advantage is logistical. China has developed distribution networks across Africa, that it is now using to distribute vaccines. The logistics unit of Chinese internet retail giant Alibaba – Cainiao – partnered with Ethiopian airlines to establish a cold-chain air bridge connecting Shenzhen to Addis Ababa, where a new airport cargo terminal will work as a distribution hub. Egypt is set to become a vaccine production center, manufacturing the Coronavac vaccine. Sinopharm has announced it will build a plant in Morocco.

Moreover, while their efficacy is lower, the inactivated vaccines from Sinopharm and Sinovac – which can be transported and stored in regular refrigerators – are better suited to Africa. Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are among the countries whose inoculation plans include Chinese vaccines. Nigeria may join this group soon. The regional picture is far from uniform, and vaccination plans will likely vary and change as governments adapt to evolving circumstances.

Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda, for example, have ordered vaccines from AstraZeneca, Moderna and Pfizer. In these cases, India – which accounted for 60 percent of global vaccine production before the pandemic – will be an important player, since the country’s drug regulator has given the green light to the local production of Covishield, the Indian brand of the AstraZeneca vaccine. South Africa had made the same choice, but then decided to switch to the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine over concerns that AstraZeneca’s would not provide enough protection against new variants.

Scenarios

While Covid-19 has not hit Africa as hard as other parts of the world, the pandemic has dramatically affected livelihoods throughout the continent. African leaders face the same pressures as in other areas to deploy effective vaccination campaigns and bring back normalcy.

Considering the obstacles to access and distribution, international aid and cooperation will not only determine the success or failure of national vaccination strategies but will also shape the regional and global balance of power. Moreover, in several African countries, the need to implement large processes will likely accelerate development, boosting digital transformation, improving communication technologies and health infrastructure.

Given this context, two scenarios are worth considering.

Realpolitik approach

In the first, slightly more likely scenario, the effort to guarantee African countries access to vaccines will be driven more by realpolitik rather than globalism. Despite China’s aggressive vaccine diplomacy, strategies throughout the continent will rely on a variety of partners and processes. The AU will play a pivotal role, boosting regional integration efforts. Besides Covax, Russia, India, the EU, and even the U.S. could play central roles.

Russia, for example, has offered the AU 300 million doses of its Sputnik vaccine and a package of financing mechanisms. The vaccine’s efficacy is estimated at 92 percent and can be stored in regular refrigerators. So far, Sputnik is being used in Algeria, Tunisia and Guinea, and the number of African countries using it will likely increase.

National vaccination strategies will adapt to fast-changing circumstances, including the emergence of new alternatives and the need to suspend vaccines, as has recently occurred in South Africa, where the rollout of the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine was halted after U.S. agencies expressed concerns over rare blood clots.

In this scenario, underperforming vaccines and scarcity would undermine China’s ambitious plans to increase its geopolitical influence, including in Africa. Fears of side effects have become an obstacle to rollout plans, and if the Chinese vaccines prove less effective or safe than advertised, diplomacy may not suffice to avoid mistrust and criticism. In the pharmaceutical field, despite Beijing’s ambitions, the West is still considered more reliable. Already there are some signs of trouble. The Philippines’ regulatory authority, for example, has granted emergency use authorization for Sinovac, but recommended its use only for healthy individuals aged between 18-59, excluding healthcare workers, who are more exposed to the virus.

Scarcity may force Beijing to make tough choices. By the end of 2021, China expects to produce 2 billion vaccine doses, enough for about 70 percent of its 1.4 billion population and sufficient to secure herd immunity. However, if those doses are exported, an immunity gap may emerge domestically.

Under this scenario, China’s aggressive vaccine diplomacy will be less effective, but Beijing will still make significant advances and consolidate its role as a leading player in global health.

Geopolitical shifts

Under a second, less likely, scenario, Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy would lead to significant, long-lasting geopolitical shifts. In this case, China would be able to greatly increase its production capacity throughout 2021, as new vaccines are developed and new facilities for mass production become operational. This scenario would also depend on the efficacy of Chinese vaccines, and China’s ability to rapidly develop and approve other effective vaccines.

Beijing’s leverage globally and throughout Africa would increase, gaining more influence in international bodies like the United Nations. These developments could speed up current changes in global politics and international relations. Moreover, by presenting a way out of the pandemic for African countries, Beijing could secure access to strategic resources at a moment when its financial commitments to developing countries are decreasing.