The UAE’s next moves in Libya

The United Arab Emirates is among a number of regional and global powers that have inserted themselves into the years long civil war in Libya. Given a recent cease-fire announcement, it will likely follow a softer approach to pursuing its interests in the country.

In a nutshell

- The United Arab Emirates continue to seek influence in the civil war in Libya

- Maritime access and key oil assets are at stake for the small gulf country

- A continued, softer approach to Libya is the likely strategy for the UAE

Since the 2011 revolution, Libya has become the perfect battleground for a clash among regional and international powers. One interesting case is the Gulf states, and particularly that of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and its approach to Libya.

Nine years ago, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar were arrayed on the same side, against ex-leader Muammar Qaddafi and in favor of the rebels who were trying to overthrow him. After the second civil war began in 2014, the dynamics shifted considerably.

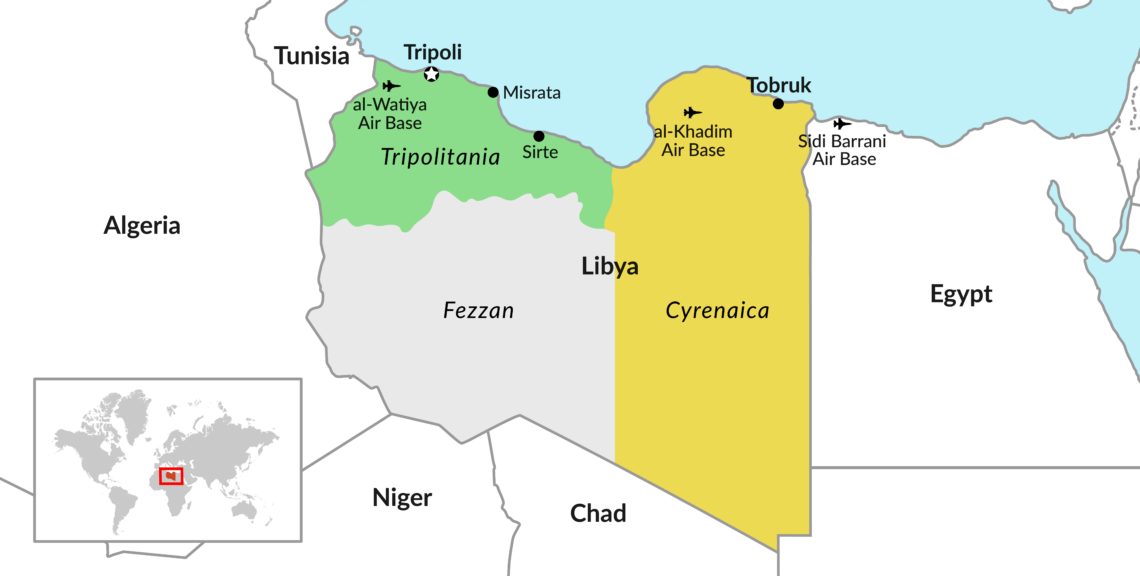

In fact, although internal alliances and the balance of power have changed, the two rival regions of the country have been backed by the same supporters since 2014. The western Tripolitania region is backed by Qatar, and above all Turkey; meanwhile, the east is supported by the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Russia and other nations, both African and European. The antagonism between the UN-sponsored government of Tripoli (the Government of National Accord, or GNA) and the one based in Tobruk (the House of Representatives, or HoR) has been personified by two very different political figures: the moderate though ineffectual Fayez al-Serraj on one side, and the militarily incapable Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar on the other.

In April 2019, Field Marshal Haftar and his Libyan National Army (LNA) began a siege against Tripoli and its militia cartels, on the pretext that their ranks included dangerous groups of Islamic extremists and members of the Muslim Brotherhood. (Despite his professed anti-Islamism, Mr. Haftar did not seem to mind tolerating the Madkhali cells in the LNA, groups of quietist Salafis who had sided with Mr. Qaddafi in the past and are opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood.)

Facts & figures

The strategy

During the intervening years, the UAE has taken an approach to Libya involving various tactics to reach its broader strategic target: fulfilling its role of a medium-sized power. This has been clear in the conflict in Yemen, and then in Libya, a country with huge natural resources that could be an extraordinary force multiplier for the Emiratis.

To be influential in a subnational geographic area (such as Cyrenaica in Libya or the southern regions of Yemen) would bring several advantages at once: weakening rivals like the Muslim Brotherhood, Qatar and Turkey; carving out a platform for projecting power, especially at sea; and becoming a real player that can take advantage of opportunities like China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

From the UAE’s perspective, maritime dynamics matter a great deal – as clearly demonstrated in Yemen, where it has operated from the southern coastal areas to the southern Red Sea, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the island of Socotra. As a result, a large part of Yemen’s coast is now controlled or influenced by actors connected to Abu Dhabi.

In Libya, as in Yemen, the Emiratis can rely on proxies and allies.

In Libya, meanwhile, the UAE focuses its approach on Cyrenaica, with an eye to Sirte and its “oil crescent,” the country’s huge petroleum hub. Moreover, Eastern Libya provides strategic depth toward the Sahel, opening a geostrategic highway both to West and East Africa (including countries like Niger, Mali and Mauritania, or Sudan and Eritrea). Cyrenaica also offers a door to the Mediterranean Sea.

In Libya, as in Yemen, the Emiratis can rely on proxies and allies operating in areas that host maritime and energy infrastructures. In fact, through the LNA-allied militias and tribes, the Emiratis are influential in the oil-rich Sirte area. However, the value of that influence is variable; recently, production stopped in some of the biggest oilfields. While the average oil production in 2019 was about 1.2 million barrels per day (bpd), it now reaches no more than 100,000 bpd – leading to a huge loss in income, estimated at almost $5 billion.

In the fight for power on the international stage, the UAE sees Turkey as an ideological antagonist, not only in the Mediterranean Basin but also in Africa, and above all in the Sahel. In the Gulf monarchies, economic targets are deeply intertwined with the need to keep a lid on dissent, via an autocratic oligarchy. They must be able to guarantee internal stability and specific economic policies. The military oligarchy that has risen to power in Egypt with Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi illustrates this model, which in some way has been replicated in Cyrenaica by Marshal Haftar. In Eastern Libya, military elites control this system, providing the UAE added value.

Military and political tactics

The Emirati strategy is rooted in two different tactics: the presence of capable proxy actors on the ground (southern militias, as in the Yemeni case); or a network of strong allies with a traditional footprint in the area of interest (Egypt, in the Libyan case). Tellingly, the UAE’s military withdrawal from Yemen has coincided with Abu Dhabi’s rising assertiveness on Libya, which would not have been possible without Egypt’s support in Cyrenaica. While the target is similar in both interventions, the methods have differed.

The UAE has been Field Marshal Haftar’s most active external backer. At the beginning of 2020, during the Berlin Conference talks and immediately after (January 12-26), Abu Dhabi organized more than 40 flights from the UAE and Jordan to the Libyan military base of Al-Khadim, which lies 65 miles east of Benghazi and was expanded a few years ago. They used strategic carriers such as the Russian-made Antonov and Ilyushin, bringing crucial military supplies to the LNA outposts in Cyrenaica – all in direct violation of the UN arms embargo.

In the first quarter of the year, the number reached more than 100 airlifters carrying weapons. (These figures are one reason why the EU’s Operation Irini, implementing Libya’s arms embargo in the central Mediterranean Sea, will end up a failure.) The Al-Khadim Air Base played a fundamental role; hundreds of loads of cargo coming from the bases of Sweihan (in the emirate of Abu Dhabi) and Assab (Eritrea) landed there, supplying 6,200 tons of weapons and ammunition.

Tactically, air strikes have been at the core of the Emiratis’ indirect support for Khalifa Haftar’s forces in Libya. From April 2019 to 2020, the UAE conducted more than 850 drone and jet strikes in the country. The Emiratis help LNA forces with modern airplanes, since the Libyan forces have fighter jets that are at least 40 years old. A nighttime attack on July 4-5 against the recently deployed air defense facilities of the Turkish military at the al-Watiya Air Base was made by Dassault Mirage 2000-9 multi-role fighters, from the United Arab Emirates Air Force taking off from the Sidi Barrani base in Egypt.

For the UAE, the El-Sisi model shows a strongman who can keep the country stable and open for business.

In human terms, the network of allies is fundamental, especially in Cyrenaica. The UAE lacks direct knowledge of Libyan local dynamics, and therefore, its relationships with tribes are mediated by Egypt, Libyan expatriates and pro-Emirati politicians like Aref Ali Nayed (a former presidential candidate and Libya’s former ambassador to the UAE). All of this has been designed with the clear target of building new alliances able to fight the Muslim Brotherhood. The El-Sisi model, in this regard, is ideal: a strongman able to stabilize the country and keep it open to business deals. For this reason, Abu Dhabi has always bet on Mr. Haftar.

Scenarios

The UAE’s strategy in Libya is stopped by the international community

This scenario at the moment is very improbable. Europe has other priorities than Libya, while the United States – the real changemaker due to its influence on the UAE – is entering a delicate stretch of the campaign season. In these final weeks before the election, every move President Donald Trump makes on the international stage will come with an eye toward domestic political concerns (for example, the recent Israel-UAE agreement).

Egypt and Russia, more involved on the Libyan stage, are not interested in a strategic departure by the UAE, although at the moment, Qatar and above all Turkey are playing their cards to eliminate Mr. Haftar.

The UAE maintains a “softer” presence in Libya

This is the most probable scenario. The UAE will be pushed by Egyptian and above all Russian allies who, by now, are close to an agreement with Turkey; this was also manifested by the cease-fire proclaimed by the GNA and HoR in recent days. The Emiratis would continue to support the HoR and its president Aguila Saleh at the expense of Field Marshal Haftar, who at this point is too weak and militarily disappointing.

In this case, the support will be more diplomatic, using local and international actors, and manifested not via military means but through economic resources. As we learned after the 2019 Riyadh Agreement in Yemen, which was based on a power-sharing government, the UAE is a master in soft power. That could happen again in Libya, using underground methods.

The UAE makes a push for complete support of Marshal Haftar in the face of a weak international community

To realize this scenario, the United Arab Emirates should significantly increase the military investments it has made so far in Libya. But it should expect Russia and Egypt to do the same – and this is the problem. The UAE is geographically far away from Libya, and has always used mercenaries and foreign weapons on the ground. To win the war, the UAE would like to have full support from Russia, Egypt and France, which is very unlikely.

Despite the weakness of the international community, it is difficult for the Emiratis to influence Marshal Haftar as they have done over the past two years. For one, the oil production crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has reduced the value of UAE’s oil-adjacent assets, scrambling somewhat the country’s typical calculus in foreign relations. At the same time, the Marshal proved to be weak and above all an incapable strategist, and not up to the expectations of his Gulf allies.

Finally, the presence of Turkey forced all the players to adjust their approach. In this sense, it is important to read the high-level meetings pushed by Turkey with Algeria as a possible counterpart to those by Egypt.