Instability in sub-Saharan Africa: The ‘tribal’ factor

The protests in South Africa highlighted Africa’s struggle to overcome ethnic divisions. Tribal and religious loyalties supersede national ones, making it difficult to create a united national polity. States that overcome tribalism successfully will have a greater chance of achieving stability, and therefore attracting foreign investment.

In a nutshell

- Many African countries still struggle with ethnic divides

- Unified nations have usually been through several conflicts

- Overcoming ethnic hostilities is a first step toward prosperity

In early September, a surge of violence erupted in several cities in South Africa. In Johannesburg, Durban and Pretoria, mobs shouting xenophobic slogans attacked immigrants, setting their houses, hostels and businesses on fire. At least a dozen people were killed and scores have been injured.

Following these events, a series of reprisals took place in Nigeria, from where many of the victims hailed. In Lagos, angry mobs stormed branches of South African companies like grocer ShopRite and telecommunications giant MTN.

Meanwhile, tension between the countries’ governments has been rising. Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari sent a special envoy to South Africa to protest the violence. The National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS) has called for all South African businesses to leave Nigeria.

The repercussions in other countries give the conflict a new dimension.

Though the coverage in large Western media outlets was subdued and some of the videos on the internet purportedly showing the violence were fake, the numbers involved are still shocking. The brutality threatens the image of postapartheid South Africa as “the rainbow nation,” a place where the formerly oppressed and the former oppressors were building a peaceful, multiethnic society.

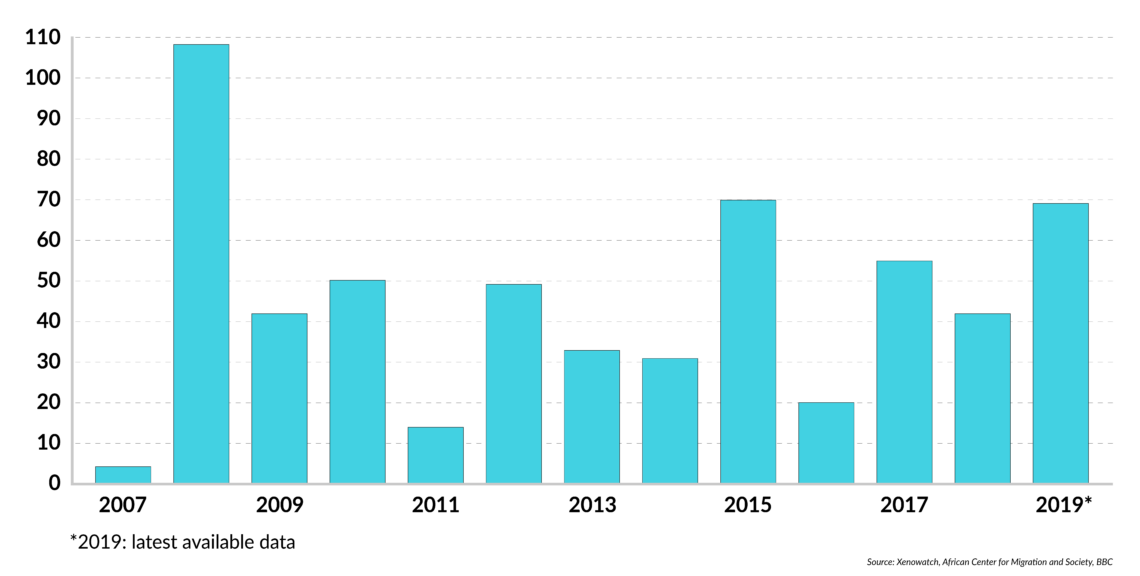

This model has been under threat for many years. Xenophobic violence peaked in terms of the number of victims in 2008 and 2015. Since then, however, there have been regular anti-migrant demonstrations. This time, the repercussions in countries whose nationals were attacked – Nigeria, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique among others – give the conflict a new dimension with broader implications.

Us versus them

There are about 4 million immigrants in South Africa, the bulk of whom came from neighboring countries. Some 800,000 come from distant Nigeria. The reemergence of violence based on national or ethnic identity seems to have surprised the international media, which seems reluctant to admit that antagonism is growing between two of sub-Saharan Africa’s leading countries.

Facts & figures

South Africa: Attacks against foreigners

Threats, attacks and killings against foreigners in South Africa

There are important economic and social factors driving the increased xenophobia in South Africa’s urban areas. Immigrants are perceived as cheap labor that competes with locals and undercuts wages. Furthermore, identity and tribal factors are crucial touchstones in this equation. The “us versus them” paradigm has become pervasive, becoming a way to distinguish friend from foe.

Understanding this phenomenon is essential for interpreting politics in sub-Saharan Africa. It is at the root of some of the bloodiest conflicts in postcolonial societies there. To better grasp its role, a review of the history is necessary.

Nation-building

In Europe and the Americas, nation-states have typically been built through two phases of conflict. First, there is a war of independence against the overlords – empires or colonial powers. Second, internal conflict and civil war follow. In the aftermath, the victors and losers forge peace and begin consolidating their nations. They create a community united by past glories, present challenges and a desire to stay together. Cultural factors, such as a common language, also play a decisive role. France, the United States and many other countries throughout Europe and the Americas have followed this model.

For a significant number of sub-Saharan African states, however, independence in the late 1950s or early 1960s was granted by colonial European nations – France, the United Kingdom and Belgium. These powers often found that acquiescing to political independence was a handy way to balance their interests, allowing them to maintain significant political and economic influence without the burdens of maintaining a military presence and institutional repression.

Countries that have had independence and civil wars have been better able to neutralize tribal divisions.

The newly independent states were admitted as full members of the international community, but various tribal and religious loyalties remained. These differences were at the heart of terrible conflicts like the Biafran War in Nigeria and the Rwandan genocide.

By contrast, countries that had to fight for independence, developing political or revolutionary movements to do so, and which later went through civil wars, have been able to neutralize tribal divisions. This is what happened in former Portuguese colonies, as Lisbon refused, until the Carnation Revolution in 1974, to give up its overseas dominions.

Exploiting the divide

Religious divisions and ethnic (tribal) identities are still the most important sources of conflict in Africa. Even in Northern Africa there are striking examples attesting to the persistence of these destabilizing factors: the Algerian civil war between the government and Islamic groups; the constant tensions in Tunisia; the bloody civil war in post-Qaddafi Libya or the tension between the army and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

Sub-Saharan Africa follows the same pattern of religious-tribal divide and conflict. Terrorist organizations like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State have used these factors to spread their ideologies and grow their networks. A case to watch is the insurgency in Mozambique’s province of Cabo Delgado, which erupted in late 2017. Tribal, religious and socioeconomic divisions have all converged in this conflict.

A group known as Ansar al-Sunna is behind the attacks in Cabo Delgado. It has targeted areas where gas exploration and extraction activities are taking place. Inspired by radical forms of Islam, Ansar al-Sunna has been recruiting young people in rural areas who belong to the Mwani ethnic group.

The Mwani are rivals of the Makonde people, who once supplied most of the guerrilla fighters for the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo) in its struggle against the Portuguese between 1964 and 1975. Today, the Makonde have significant representation within the state hierarchy, the government and Frelimo (the ruling political party since independence). President Filipe Nyusi is a Makonde, as are many of the top military brass. The historical antagonism between the tribes has made the Mwani more prone to engage in hostilities against the government, which they identify with the Makonde.

This phenomenon is not exclusive to Africa, of course. In Iraq and Syria, for example, tribal or clan factors are still important determinants of national politics. A stable sovereign state requires a political community, a monopoly on political legitimacy and a respect for its hierarchy. Competing loyalties – to tribe or clan – could translate into serious trouble.

Tribal and ethnic identity factors still haunt South Africa: the majority blacks, whites, Indians, and more recently the emerging Chinese community are all perceived against the backdrop of their ethnicity – and politically, they tend to act according to their ethnic identities. Even South Africa’s armed forces have quotas for the different groups, maintaining a rough proportion with their share of the population.

Angolan exception

Nigeria has more than 200 tribal groups and a religious divide between Islam in the north and Christianity in the south. Despite the country’s large military, the jihadist organization Boko Haram (since 2015 officially the Islamic State in West Africa) has been conducting terrorist activities for a decade and has killed thousands of people.

South Africa is now following a pattern of interethnic violence. Currently, the attacks are directed against foreigners, but sentiment could turn against other ethnic groups. The white minority (about 4.8 million) is under threat after Parliament passed a motion to review the property ownership clause of the country’s constitution to potentially allow for the expropriation of land without compensation. If implemented, such solutions would have a hugely negative impact on the white farmers of the northern Transvaal region and could significantly hamper the economy.

Presenting a clear contrast to the trouble brewing in two of Africa’s biggest countries is Angola. The southwestern African nation underwent a more traditional nation-building process: An uprising against Portugal’s colonial rule began in 1961. The government in Lisbon resisted, refusing to opt for decolonization. The Angolans had to fight for their freedom, which came in November 1975. A long civil war ensued, ceasing only in 2002, with the victory of the MPLA government against the rebels of UNITA. The latter was supported by South Africa and the United States, the former by the Soviets and Cubans. After the end of the Cold War, foreigners withdrew their support and the MPLA defeated UNITA, killing its leader, Jonas Savimbi, in combat.

Religious divisions and ethnic identities are still the most important sources of conflict.

One consequence of the war was detribalization. It pushed people from the countryside to the cities, which were considered safer. Newcomers mixed into the urban population, increasing interethnic contact.

After UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi’s death, a truce was declared, a peace was negotiated, and rebel militants were integrated – without reprisal – into the Angolan Armed Forces. As a result, and despite its current economic difficulties, Angola is one of the most integrated and stable societies in sub-Saharan Africa.

Persistent problem

During the Cold War, the bipolar nature of geopolitics meant there was more tolerance for authoritarian regimes. With their strong militaries and centralized power, such governments were able to counteract political fragmentation and interethnic conflict.

As these regimes fell and democratization took hold, tribal conflicts reemerged in places like Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In such countries, tribal allegiance still dominates political affiliation, endangering the monopoly on political loyalty that a stable sovereign state requires.

A stable sovereign state requires a political community, a monopoly on political legitimacy and a respect for its hierarchy.

Countries like Nigeria, South Africa and the DRC face serious challenges caused by ethnic and tribal antagonisms. Other countries, like Angola, were able to leverage their detribalization processes and have a better shot at consolidating stability and national unity, which is crucial for a prosperous economy and society.

With a resurgent wave of nationalist identity throughout Europe and the Americas, the end of Pan-Africanism and the continent’s looming security and economic difficulties, Africa’s 54 countries would do well to accelerate their national integration and try to offset tribal and religious divisions. That is easier said than done, of course, especially since the current global zeitgeist has made religious and ethnic identities decisive factors of unity and conflict.

One factor that could push the process along is help from the rest of the world for African governments to create strong, accountable political institutions that can tackle fragmentation, tribalism, terrorism and religious extremism. Global powers such as China, Russia and Japan, as well as European countries and the U.S., are all getting more involved in Africa economically. These countries could make state-building (a first step toward nation-building) a priority in multilateral initiatives.

Scenarios

Can we therefore expect multiethnic African countries to move faster toward “nationhood,” becoming more united, with the state gaining a monopoly on political loyalty?

Such a scenario is unlikely in the short term. Several factors are working against these countries: their economies are still highly dependent on the outside world, their elites are not unified and the post-Cold War introduction of European-style party democracy begets division. In Europe and the Americas, statehood was born of strong monarchies and centralized institutions that had clear authority over their territory and were served by large national armies.

The African countries that will more easily achieve political unity will be the ones that can maintain stability and therefore attract foreign investment. Other countries – even large ones that present themselves as economically robust – will struggle with the consequences of political and cultural divisions. The lack of national unity will threaten their peace, stability and economic development.