India’s evolving strategy in the Middle East

India is forging profitable new partnerships with Sunni Arab states as its economic profile grows and its ties with the U.S. and Israel strengthen. The changes are causing tension with its old ally Iran, which New Delhi still needs to keep Pakistan in check. This balancing act could leave India vulnerable to the Middle East’s notorious instability.

In a nutshell

- India’s ties with Sunni Arab states are growing closer

- The shift is causing tension with longtime ally Iran

- India’s ability to act in the region will remain limited

There are few regions in the world where India has walked a more careful diplomatic tightrope than West Asia – the term New Delhi uses for the Middle East. India’s old policy was to cultivate bilateral relations with a few countries, see to it there was a welcome mat in the Persian Gulf for its migrants, and ensure a steady flow of oil and remittances to its economy. As its relationships in the region multiply and fault lines deepen, India will struggle to maintain its balancing act. Nascent strategic economic relationships with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia further complicate the situation.

Passive policy

Historically, India’s interest in the Middle East has centered around the Persian Gulf. By the 1980s, New Delhi had developed a set of relationships in which it was the junior partner. Several million Indian immigrants worked in the Sunni Arab monarchies, with large concentrations in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Indian business used Dubai as an overseas investment and trading hub. Oil was imported from Iran, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait while natural gas was shipped in from Qatar. Added to the mix was a cautious decision to normalize relations with Israel in 1992, an element in a post-Cold War rapprochement with the United States.

Indian diplomats described their West Asia policy as a set of bilateral relations, and their primary task was ensuring these never became entangled. India’s views on the region were, as official pronouncements would repeat ad nauseam, “nonprescriptive and nonjudgmental.” The flip side of this stance was that New Delhi had no influence on anything that happened in the region. Wars in the Middle East triggered two oil-price shocks that helped precipitate, via inflation, a political crisis (which led to a state of emergency and the suspension of democracy in India) in 1975 and an economic crisis in 1991.

India’s cautious stance arose from the enormous one-sidedness of the economic relationship. The Middle East provided India with $40 billion in remittances, as well as 60 percent of its oil and 90 percent of its natural gas imports. New Delhi also feared contamination by the region’s extreme religious politics: India is home to the third-largest populations of both Sunni and Shia Muslims. India did not even protest as Saudi Arabia and the UAE for years helped finance the arsenal, nuclear program and terrorist networks of its archrival, Pakistan.

New Delhi’s relationship with Tehran was rich in history but poor in economics.

India was able to establish ties with Israel with minimal fuss in large part because no one believed New Delhi could play a significant role in the Levant. India also went to great pains to keep a door open for Iran. Tehran was seen as more hostile to Pakistan and its proxies, like the Taliban, as well as theologically less poisonous than Saudi Arabia. However, New Delhi’s relationship with Tehran was rich in history but poor in economics. India imported a lot of oil but exported little in the way of people.

Shifting sands

In the past few years, West Asia has become a very different geopolitical landscape for India for several reasons.

First, its economic relationship with the Gulf has changed. Remittances are on a downward trend, as businesses in Arab states employ more local workers and Indians are replaced by cheaper labor. But India has become such a large consumer of fossil fuels from the region – it is the fastest-growing importer of oil and projected to be the main driver of global gas demand after China – that today it is being wooed by Gulf countries anxious to secure a lucrative market. India’s technology sector has also begun to attract investment from regional wealth funds.

Second, India’s increasing closeness to the U.S., along with its expanding military capabilities in the Arabian Sea, have caught the attention of the UAE and others seeking new external partners in the region. That Israel has emerged as one of India’s main weapons providers only enhances Sunni Arab interest.

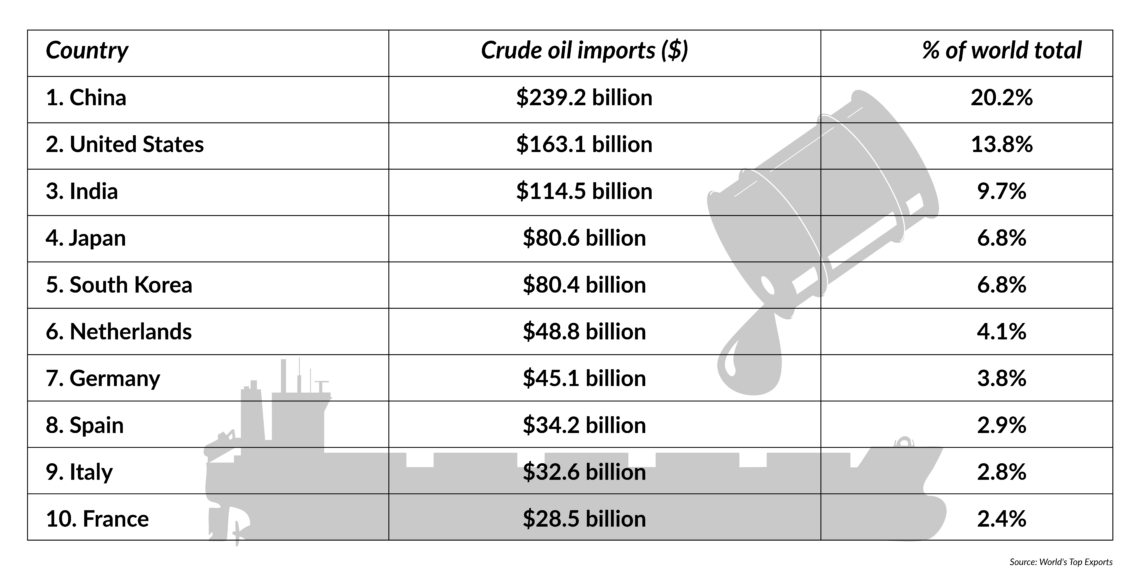

Facts & figures

Top oil importers, 2018

Third, Pakistan is losing salience in the region because of its poor economic performance and its inability to control homegrown jihadist militants. Islamabad had offered to be the backup army for the Sunni monarchies. But when they asked Islamabad to take up arms in the Yemen conflict, its military refused. While Pakistan remains the nuclear plan B for Saudi Arabia, that relationship no longer exerts a veto on closer ties with India.

At a time when the Middle East is an even more lethal geopolitical minefield than before, India has entered a set of strategic relations with various regional players that it did not have in the past. Israel is now an indispensable military partner. The trade route to Afghanistan through the Iranian port of Chabahar is an important element of India’s policy to keep a non-Taliban regime in Kabul. Overlaid on this is a new investment-driven economic relationship with Abu Dhabi and Riyadh.

New economics

Arguably, the most surprising twist in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s foreign policy was his state visit to the UAE in 2015. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed made it clear he wanted a new all-encompassing relationship with India that would include military elements. New Delhi’s assessment was that Abu Dhabi wanted more strategic options as the U.S. turned inward, Pakistan weakened and Iran expanded its influence. Prime Minister Modi told the UAE it would have to put its money where its strategy was, and Abu Dhabi promised to invest $65 billion in India over a five-year period – with more to come.

There has been an announcement of a new investment in India nearly every month by some of the UAE’s largest firms.

Since then, there has been an announcement of a new investment in India nearly every month by some of the UAE’s largest firms, such as its trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund, DP World or Abu Dhabi National Oil Company.

Saudi capital has followed in the UAE’s footsteps. The Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia has reportedly provided $20 billion to Japan’s SoftBank for investments in Indian start-ups and technology companies. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman visited India in February. Unlike the UAE, the Saudis remain militarily close to Pakistan and Prince bin Salman visited Islamabad before arriving in New Delhi. But the crown prince accepted that India is crucial to his country’s economic future and promised $100 billion in investments. The giant Saudi oil firm, Aramco, has begun exploring the possibility of buying a quarter share of India’s largest oil and gas firm, Reliance Industries Limited. This follows an earlier unsuccessful $20 billion bid for another Indian firm Essar Oil (now Nayara Energy). Saudi diplomats say these moves are part of a plan to entrench Saudi Arabia in India’s energy sector.

India has underlined to all of its new Middle Eastern partners that they should not expect it to take sides in their political rivalries. The question is whether this position will be tenable in the long run. Its relationships with Israel and the Arab monarchies are almost unrecognizable from what they were 20 years ago. A senior Indian diplomat, commenting on the growth of the UAE’s economic profile in the country, said it was not inconceivable that after Washington and Tokyo, Abu Dhabi could emerge as India’s third transformational relationship.

Scenarios

India’s present and most likely path is to continue walking the tightrope, even if there are strong crosswinds. The country is now a strategic partner to Israel and Iran, and an energy partner of Saudi Arabia and Qatar. New Delhi will continue to plow its independent furrow in the region for as long as it can. It will therefore avoid developing a genuine region-wide policy with problem-solving elements. India is strictly limited to the role of a supporting player – for example, by serving as messenger between Tel Aviv and Tehran.

A second scenario would see India drifting slowly away from Iran. Many in Tehran already treat India with suspicion given its closeness to Israel and the U.S. As the size of the economic relationship with Abu Dhabi and Riyadh grows, India will find its interests tilt toward those of this de facto anti-Iranian front. Additionally, if there is ever a Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, a key tie in the Indo-Iranian relationship will unravel. New Delhi has sought to reassure Tehran, trying to find ways around U.S. trade sanctions and increasing its diplomatic engagement, but the lack of tangibles in the relationship is evident.

The least likely scenario would be for India to realize that instead of trying to tiptoe around these wounds, it would be better to use its influence to heal some of them. That possibility remains distant because New Delhi believes it lacks sufficient influence and interest to undertake such a role. Upon being asked whether New Delhi would get involved in peacemaking in the Middle East, India’s senior diplomat replied, “Kicking and screaming.”