2019 Global Outlook: The Fertile Crescent

The most important development in the Middle East has been the end of Syria’s civil war, which was unequivocally won by the Baath regime. But with the announced U.S. withdrawal from Syria and the victory of the Assad regime and its Russian and Iranian sponsors, the way could be cleared for an explosive confrontation with Israel.

In a nutshell

- After defeating an Islamist challenge, the Fertile Crescent’s Arab States are still shaky

- Iraq must cope with a restive Shia south, Kurdistan, and increasing pressure from Iran

- A U.S. withdrawal from Syria would leave Vladimir Putin to dictate peace terms

- The danger of an Israeli-Iranian confrontation in Lebanon and Syria has not gone away

2018 in the Middle East was a handful. That especially applies to the Fertile Crescent, where both on the level of individual countries and across the whole region, last year saw developments of great significance for the future.

Probably the single most important of these was an apparent end to the civil war in Syria, which came after the crushing of the huge territorial base held by Islamic State (ISIS) in Iraq in 2017. This represented a major victory for Syria’s ruling Baath regime as well as for the entire Arab state system erected after World War I, which survived the hammer blows of a powerful religious opposition.

One hundred years after they were created by the great colonial powers, Iraq and Syria survived the biggest internal upheavals they had ever experienced, while Jordan managed to pull back from the brink of a similar civil war. The first two countries suffered enormous losses in human life and infrastructure, but they survived. Prophecies by pundits and impressionable scholars about the impending demise of these Arab states proved premature.

At the same time, however, it must be borne in mind that the victory of central governments in these countries could not have happened without huge support from European powers that created these states: this time buttressed by the United States (absent from the region a century ago) and Russia. This victory was also far from complete, since the contradictions between the main ethno-sectarian components in each of these three countries – and Islamic and semi-secular forces – remained.

Far from being eradicated, Islamist rebels have reverted to guerilla warfare and clandestine work.

By the end of 2018, the Islamist rebels were down but not out. Far from being eradicated, they had simply changed strategy. Instead of seeking a territorial base for an Islamic quasi-state, they reverted to guerilla warfare and clandestine work. These activities will continue in 2019. If reconstruction and other forms of state support do not reach the disaffected regions in each country, Islamist rebels will pose a renewed threat.

Iraq: Street revolt

In Iraq, a new danger could be identified. Its nature is very different from ISIS, yet poses no less a threat to the fragile democratic government. Following an election campaign in which the public demonstrated its disillusionment with the regime’s performance, between July and December the Shia south, led by the city of Basra, rose up in an open, if unarmed, revolt.

Baghdad’s corruption and ineptitude, combined with drought and water shortages partly caused by Iranian and Turkish egotism, provoked mass street demonstrations that raged for months with no meaningful improvement. Water in the south is still scarce and polluted, public services are completely inadequate or nonexistent, and unemployment among young people is above 20 percent. Even though the demonstrations had ebbed by December, expectations for Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi’s new government are high, and if they are not met, at least in part, Basra will rise again.

Any renewed protests will be accompanied by stronger demands for autonomous status along the lines of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in the north. Such demands are perfectly constitutional, but represent a deadly threat to Baghdad because Basra is where some 85 percent of Iraq’s oil is being produced. This Shia-on-Shia confrontation is nothing new for Iraq: in 2008, Muqtada al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army was very close to driving government troops out of Basra. This time, support among the populace for the mostly unarmed anti-government protests was far wider.

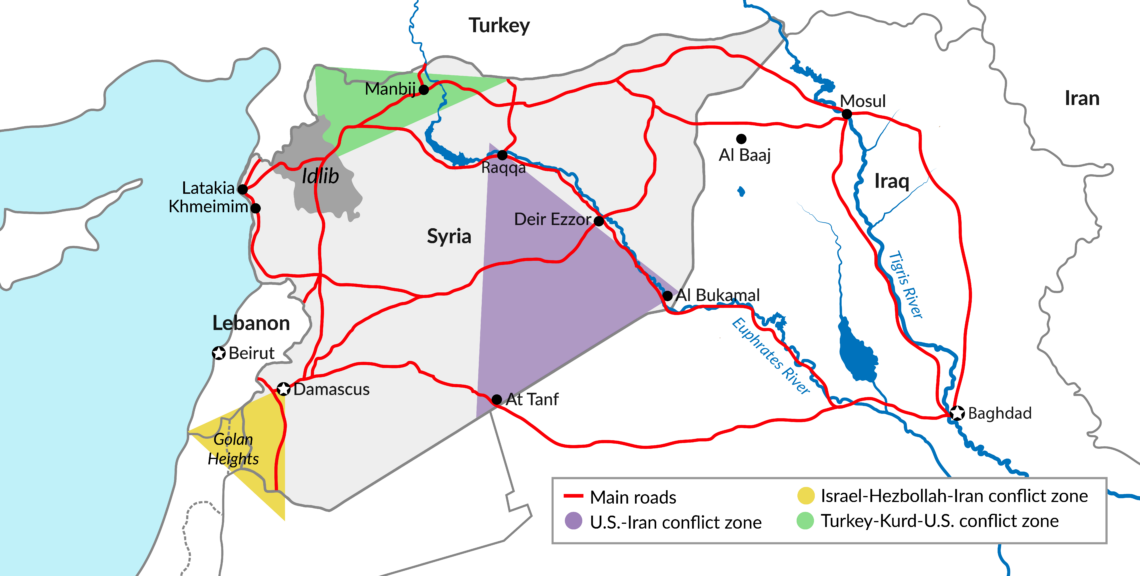

Facts & figures

Conflict zones in Syria

Another test for Baghdad in 2019 will be striking a balance between the U.S. and its allies, including the Arab Gulf states, and Iran. A crucial indication of which way Iraq is leaning will be the extent of its cooperation with the American embargo against Tehran. Unless Washington finds a way to replace Iran as a commercial partner for Iraq (mainly through refining Iraqi crude and supplying gas and electricity), it is almost certain that Baghdad will find ways to circumvent the embargo. The only feasible solution is increased economic cooperation with the Arab Gulf states.

Another test will be who Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi chooses as interior minister. If the appointee is a staunch supporter of Iran (as was the case with a previous, unconfirmed nominee), there will be reason for American and Gulf-Arab concern, since that will put the lives of the entire cabinet at the Tehran’s mercy. Asking the 5,000-strong U.S. force in Iraq to leave would also be an ominous sign.

Whatever happens, the prime minister and President Barham Salih – the new power duo atop Iraq’s political system – will necessarily find 2019 to be a highly challenging year. Lacking a solid parliamentary majority behind them, it is unclear whether they can survive at all without major concessions to Iran. If they fall, Iraq will be thrown again into deep crisis.

Syria: Defusing Idlib

In Syria, there is still a large concentration of Islamist rebels, including ISIS, in Idlib province in the northwest, along with some holdout ISIS elements in Hajin, east of the Euphrates. The rebels in Idlib enjoy some Turkish support, resulting in a tacit agreement by the Damascus government to leave them alone for now. However, it is difficult to imagine that President Assad would accept a long-term presence of his worst enemies (especially the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front, which has since renamed itself Jabhat Fatah al-Sham, or “Syria Conquest Front”) in such a central part of the country. For their part, his Russian allies will also find having hostile territory so close to their port and air facilities in Latakia and Khmeimim difficult to stomach.

Renewed fighting in Idlib would trigger a Russian-Turkish crisis, which both sides are trying hard to avoid.

One should thus expect 2019 to bring a major change. Renewed full-scale confrontation is possible, but more likely is a Russian-mediated evacuation of fighters and some civilians from Idlib into the Turkish-held part of northern Syria (along the Turkish border), from which the Turks are busy cleansing the Kurdish population. This will enable President Assad’s troops to take over Idlib peacefully. Renewed fighting would certainly trigger a severe Russian-Turkish crisis, which both sides are trying hard to avoid. This year will also see a continued Iranian effort to export their version of Twelver Shia Islam into the Sunni and Alawite parts of Syria.

Last year, the Turks found themselves at odds with the U.S., their NATO ally, over the future of the Kurdish de facto autonomy (Rojava) in northern and eastern Syria. The Kurdish self-defense forces (People’s Protection Units, or YPG) provided ground troops needed to eject ISIS from most of Syria, while the U.S. sent some 2,000 Special Forces troops, weapons and supplies, plus air support. Ankara feared that the Syrian Kurds were supporting the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), with which the Turkish government has been waging an off-again, on-again guerilla war since the late 1970s. These concerns had put an almost insuperable strain on U.S.-Turkish relations.

Syria: Kurdish options

Alexander the Great untied the Gordian Knot with his sword; U.S. President Donald Trump did the same with his tongue. His announcement from the White House on December 19 that the U.S. would end its military presence in Syria may take several months to implement, and is already being hedged by conditions, but the decision itself appears irreversible.

If the U.S. really abandons the Kurds after they helped so much against ISIS, American credibility will be mud. However, President Obama had done much the same, dropping the Iraqi Sunni tribes after they had provided invaluable help against al-Qaeda in Iraq. Even knowing this, the Syrian Kurds still aligned themselves with the U.S. The lesson seems to be to accept American help when it is offered, with the understanding that it is purely tactical. This does not bode well for long-term U.S. strategic aims.

The Kurds now have a brief breathing space to prepare a response. Militarily, they are already shifting forces from the east and southeast, where they were fighting ISIS, to the north; they are also appealing for help to Iraqi and Turkish Kurds. Politically, they are negotiating with the Assad regime for a return of government forces to the Kurdish enclave.

The latter option is far safer for the Syrian Kurds, even if it comes at the cost of giving up their limited autonomy. Turkey may not yet be ready for war; but when it completes preparations, it is fully capable of defeating the Kurds, even at a heavy cost. The international community may express some verbal support for Kurdish autonomy in Syria, but effective assistance is difficult to imagine; in any case, without access to the high seas, Rojava is vulnerable to economic blockade.

Whatever happens, the final arbiter of the future of Idlib and the Syrian Kurds will be Vladimir Putin. In the end, he will be the one telling President Assad, President Erdogan and the Kurdish leaders what to do, and they will obey.

Syria: Blocking position

Southeastern Syria, abutting the Iraqi and Jordanian borders, is its own special case. Throughout 2018, the Americans kept small Special Forces detachments there to block Iranian logistics routes to Damascus and Lebanon, offering to withdraw their forces if the Iranians agreed to evacuate their own. This made a lot of strategic sense.

Near At Tanf, a small Syrian town on the Baghdad-Damascus highway just north of the border triangle where Iraq, Jordan and Syria meet, one such unit served as a cork, preventing movement of Iranian reinforcements and supplies. While there are other overland routes from Tehran to Damascus, they take a more circuitous and less safe path through Sunni and Kurdish territories to the north.

The U.S. presence in Syria served as a very effective pressure point against Damascus and Moscow alike.

A little further north, along the border with Iraq, another small American force controls a key Syrian oil field near Deir Ezzor. This also served as a very effective U.S. pressure point against Damascus and Moscow alike. These Special Forces units could call on almost immediate air support from the large American air base at Muwaffaq, in northeastern Jordan, as Russian private military contractors discovered at their cost during a February 2018 attack.

When these forces are withdrawn, Iranian pressure on the Iraqi government to allow Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps units and missile deliveries to use the overland route through Iraq and on to Syria will be substantial. Until now, these deliveries have been made directly by air to Damascus.

Israel vs. Russia

Israel was surprised by President Trump’s decision. From an Israeli perspective, giving Iran free passage through Iraq will be very problematic. Israel is likely to attack the arriving Iranian units while they are still exposed in the open Syrian desert. However, this means that, unlike the situation today, the Israeli warplanes would have to fly deep into Syrian airspace. Israel would then need to protect its strike force against far heavier Syrian antiaircraft fire.

Even so, the main threat will come from Russia. Over the past year, the Russians have become increasingly annoyed at the damage inflicted on the Assad regime’s prestige and the danger posed to their own forces by Israeli aerial attacks against Iranian and Hezbollah targets in Syria. Any widening of those attacks will be sure to meet with Russian objections.

Nor can the Israelis count on political and strategic backing from their American allies in this context. President Trump shows less inclination than his predecessors Lyndon Johnson (1967) and Richard Nixon (1973) to extend the American security umbrella over Israel in the event of a conflict with Russia. That means Israeli leaders will face some tough strategic decisions over Syria this year.

On the international level,despite more than half a million dead and roughly 10 million displaced citizens, President Assad’s Syria will be welcomed back to the Arab League and most, if not all, Arab states will reopen their embassies in Damascus. The U.S. will also try to convince Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states to help Syrian reconstruction in the hope that this will limit Iranian influence.

Jordan: Still brittle

Jordan’s political stability is deceptive. Over the past four years, since a large tribal protest in the southern city of Maan declared allegiance to ISIS, the Jordanian monarchy has withstood numerous Islamist challenges. Between 2012 and 2018, some 2,000 Jordanians fought in Syria as members of Sunni Islamist movements, and most of them will be returning home this year.

Even within Jordan’s leadership circle, there are demands to limit King Abdullah II’s extensive executive powers and turn the country into a British-style constitutional monarchy. The kingdom’s financial situation is growing so dire that its economy may be threatened with collapse without significant financial support from the Gulf Arabs and the U.S.

Democratization could be good news, but only if one ignores Jordan’s highly volatile political arena, which is mostly under Islamist influence. If democratic reforms were introduced at one fell swoop, rather than incrementally, they would probably spur Islamist radicalization and the outbreak of a new crisis with Israel – perhaps even another Intifada on the West Bank.

With Israel already on edge about threats from Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in southern Lebanon and Iran in Syria, opening another hostile front in Jordan is bound to make politicians and security officials even jumpier.

Iran vs. Israel

There was considerable tension in the five-sided security conflict between Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Iran and Russia but, despite our predictions, no major confrontation took place there last year. Israel continued to target Iranian installations in Syria. Tehran chose not to react because this front is very far from Iran and very close to Israel, and the Israeli strategic advantage is overwhelming.

Accordingly, the Iranians scaled back their effort to establish themselves in Syria. Russia was outraged when one of its surveillance planes was downed by Syrian ground-to-air defenses (responding to an unrelated Israeli incursion into Syrian airspace). Russia’s subsequent delivery of air-defense equipment to Syria – including the relatively advanced S-300 missile system – will limit but not eliminate Israeli operational capabilities.

Israel and Iran will keep sparring in Syria, but in 2019 Russia will be taking a much pricklier stance toward Israel’s activities. The Kremlin is not pleased by the prospect of large-scale Iranian penetration in the Levant, but it is even less happy to see Israeli air operations over Syria and Lebanon. Israel can expect even less freedom of action as Russia puts its own S-400 missile batteries on a hair trigger.

After President Trump’s announcement, Iran will try to incorporate Syria into its strategic offensive-defensive belt.

This will tempt Iran to resume its efforts to establish Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and missile bases in Syria. Moscow will likely attempt to curb these activities, but in the last analysis, will not sacrifice its alliance with Tehran. After President Trump’s announcement, Iran will try to take advantage by incorporating postwar Syria into its strategic offensive-defensive belt. Israel, however, cannot tolerate Iranian expansion on its border. This will keep friction on the Syrian front high.

Lebanon: What if?

The situation is no less threatening in Lebanon. In 2019, Israel is more likely to initiate an attack against Hezbollah than the other way around. This is because the Israelis cannot expect the United Nations or the Lebanese government, which presently does not even exist, to dismantle Hezbollah’s precision missiles industry. No one inside Lebanon can challenge Hezbollah today.

The Israeli dilemma is that if they do not attack or otherwise disable those factories (as they did in 2018, by interdicting deliveries of subassemblies and parts), by the end of this year Hezbollah will have not a few score but several hundred precision-guided missiles. This is a major strategic threat.

However, if the Israelis choose to strike the missile factories in Lebanon, it must assume that Hezbollah will respond with everything it has. Because Israel’s Iron Dome short-range system cannot effectively counter a high-volume attack of 1,000 or more missiles and rockets per day, this means Israel can expect to suffer heavy damage and potentially hundreds of casualties. The fact that Israel could retaliate by bombing Lebanon back to the stone age is no consolation.

Of all the possible developments in the Middle East during 2019, the situation on Israel’s “Northern Front” is the least certain to this author. Israel’s security establishment may decide to take out Hezbollah’s missile factories, but it is equally possible they will decide that now is not the time for an all-out war with Hezbollah.

As unlikely as it seems now, if the Israeli-Iranian friction over Syria reaches a combustible point in 2019, Tehran may order Hezbollah to join the fray. As the Syrian civil war has shown, the Iranians are ready to fight to the last Shia Arab and Afghan.