AUKUS raises temperature in Southeast Asia

ASEAN has long been a divided organization, and the new AUKUS pact brings new risks that threaten to further marginalize it. If the association’s member states fail to regroup, they could end up completely sidelined as geopolitical actors in their own neighborhood.

In a nutshell

- AUKUS is a consequence of ASEAN’s inertia

- The organization is too divided to counter China

- Rising tensions could result in confrontation

The trilateral security pact among Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States (AUKUS) is a big deal for the Indo-Pacific region. Since it launched on September 15, 2021, the group has stolen the show from other cooperation frameworks that have existed for much longer, including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) between Australia, India, Japan and the U.S. That the new alliance has become the main bulwark against China’s expansionist aims will likely raise regional tensions, possibly marginalizing ASEAN and destabilizing Asia.

While media attention has been focused on AUKUS’s intention to provide Australia with eight nuclear-powered submarines over the next two decades, the trilateral partnership goes far beyond that. Its members intend to share information and technology, as well as integrate security and defense capabilities. It is meant to promote the existing “international rules-based order” constructed by the Anglo-American alliance after World War II, to the benefit of countries like Australia. AUKUS also sets out to “protect … shared values and promote security and prosperity” in the prevailing international system. In short, the group aims to protect the status quo in answer to China’s ambitions as a “revisionist” power.

While the Indo-Pacific remains the main arena of contention, AUKUS is more than a two-ocean response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other expansionist projects. The UK’s central role in AUKUS adds the Atlantic Ocean into the Indo-Pacific mix, entailing a reconceptualization of global politics. The three-ocean projection will make Beijing feel more encircled and agitated. This shift to the sea favors maritime powers like the U.S. and the UK, and will likely put traditional land powers like China and Russia on a more defensive footing.

AUKUS’s near-term ramifications are not hard to delineate. The Quad did not fulfill its purpose because the combined heft of India and Japan has been insufficient to take China to task. Despite its issues with China, India’s autonomy precludes being roped into the Anglo-Saxon axis against Beijing. Similarly, Japan sees China as a geopolitical rival and security threat but needs to chart its own course for dealing with Beijing. Tokyo’s recent conflicts with South Korea constrain the country’s latitude vis-a-vis Beijing in contentious arenas, such as the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

It would be challenging for Tokyo to have tensions both with Beijing and Seoul at the same time. Hence, Japan does not want to provoke China. In fact, no country with a direct land or maritime border with China is willing to openly incur Beijing’s wrath. This is why the Quad can only go so far. AUKUS goes further partly because it comprises only countries with no direct borders with China.

The UK and the EU

AUKUS is deeply consequential for both the UK and the European Union. For the UK, being out of the EU means having to carve out its own niche. But for that, London must ask itself what kind of great power it wants to be. Australia does not lack strategic clarity in this regard; Canberra wants to be a strong, solid middle power that will stand tall in pursuit of its national interest. The UK, however, is unclear about where it wants to go with AUKUS. Being a great power, as appears to be the UK’s intent, requires resources. It is a status that cannot be acquired on the cheap. AUKUS could further alienate the UK from the EU, which has its own Indo-Pacific strategy. Yet the UK’s connection with Australia through AUKUS is unlikely to revive old British imperial relations or boost commonwealth bonds. Australia sees the UK more as a partner and peer rather than a former colonial overlord.

For the EU’s “strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” AUKUS is an existential challenge. It comes on the heels of Brexit, whereby the UK essentially snubbed the EU by leaving the bloc after nearly 50 years of membership. By further undermining the European project, AUKUS has intensified Brexit’s impact. The maintenance of the rules-based international order, a primary objective of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy, will be harder to achieve because the AUKUS pact is aimed directly at containing China.

Moreover, AUKUS particularly enraged the French by not just hijacking a submarine procurement deal but also by posing a diplomatic affront to France. French relations with the three AUKUS countries will be difficult, complicating EU strategic engagements with Canberra, London, and Washington. It will be more demanding to maintain EU unity in the Indo-Pacific because France, which has the most forward-deployed maritime capabilities and interests in the Indo-Pacific among EU members, will likely be an outlier in its opposition to AUKUS.

Facts & figures

ASEAN perspective

AUKUS will be seen in Beijing as an act of symbolic aggression by Western powers. Chinese leadership will likely blame the Australians, first for picking a fight by accusing China of starting the pandemic and then, after a trade and tariff war as retaliation, for getting its bigger friend and cousin to gang up on Beijing. AUKUS will elicit a clear and muscular response. Already Chinese warplanes have hovered over Taiwanese skies. China’s South China Sea maneuvers may step up, its “wolf warrior” diplomacy will probably intensify, and more saber-rattling will follow. China will likely see itself as a victim rather than the aggressor. These tensions will simmer and affect ASEAN.

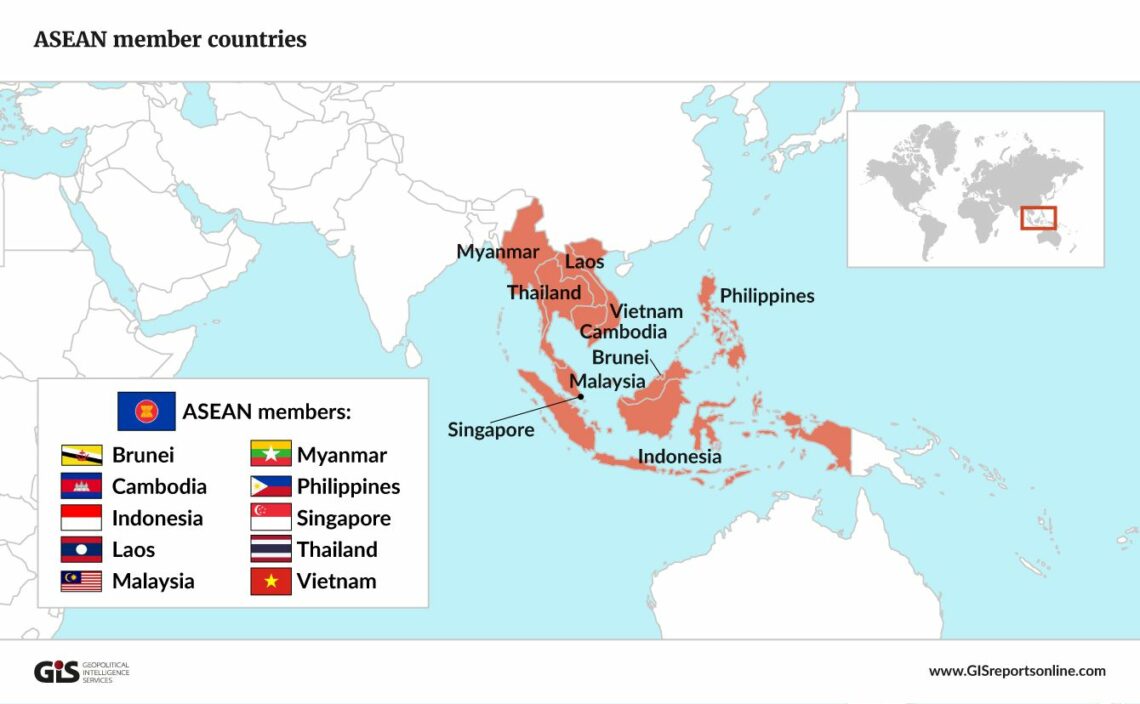

While China has divided ASEAN on South China Sea issues and brought Cambodia and Laos into its fold, AUKUS will further polarize the group, already hobbled by Myanmar’s postcoup crisis. Malaysia and Indonesia, as opposed to Singapore and Vietnam, are not in favor of AUKUS. The trilateral deal may complicate related cooperative vehicles, such as the Five Power Defence Arrangements among Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and the UK, as well as the Five Eyes intelligence partnership between Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the U.S. Although it galvanizes three members in the Five Power and Five Eyes, AUKUS may prove divisive on multiple fronts.

ASEAN centrality will thus face a further test under AUKUS, as Australia pushes back against China in Southeast Asia’s neighborhood. A more unified ASEAN is needed to maintain a central role in regional cooperation for peace and security. But the organization is increasingly prone to discord. The Quad’s recent movements and now AUKUS are byproducts of ASEAN’s inertia and inability to provide direction in its own neighborhood in view of China’s belligerence. This does not mean ASEAN will crumble or disappear, but its relevance will further diminish.

Both ASEAN and New Zealand are intent on maintaining a nuclear-free environment, which is now made more difficult by AUKUS. The Asia-Pacific has been eclipsed by the Indo-Pacific, shifting the focus from prosperity to security.

Scenarios

Something like AUKUS was bound to come along. China’s expansionism is unlikely to go unchecked while the old alliances of the West remain deeply rooted.

All this bodes ill for Southeast Asia’s hitherto peaceful neighborhood. It behooves ASEAN leaders to close ranks and realize that collaborating is more beneficial than being divided by outside powers. But this scenario appears highly unlikely for the foreseeable future.

ASEAN now faces unprecedented risks and threats in its regional security environment. If the organization fails to act as a buffer and broker among the major powers, the more likely scenario is that geopolitical tensions will rise. ASEAN’s ambition to be in the driver’s seat in the Indo-Pacific may become sidelined as major Western powers expand their presence and maneuvers in the region. This scenario could lead to a reaction – or overreaction – from Beijing, resulting in confrontation.