Australia’s historic realignment

For most of the 20th century, Japan and Australia had little reason to develop a relationship. However, China’s rise as a regional hegemon has the potential to bring the two countries closer – for example through Japan’s involvement with the Five Eyes intelligence alliance.

In a nutshell

- Japan and Australia have little to no historical ties

- Now their security interests are beginning to overlap

- The Chinese threat could bring Japan and Australia closer

The written history of Australia begins with the arrival of the British in the 18th century. This migration was to have an important impact on the geopolitical positioning of Australasia in the 20th century.

Australia long saw itself as an outpost of Europe and Britain. The country is still a member of the Commonwealth, with Queen Elizabeth II as head of state, represented in Canberra by a governor-general. During the two World Wars, it was a staunch ally of the British and lost many of its soldiers on foreign battlefields.

The remote and immense island was spared from war on its territory. The closest it came to international warfare was when Japanese fighter planes tried to enter its air space during World War II.

Recent geopolitical shifts in Asia have affected both Japanese and Australian security interests.

After the success of the “Four Asian Tigers” and reforms in China, Canberra began to shift its focus to Asian economies. In the late 1980s, the country became aware that it had to resolutely position itself in Asia to profit from the economic boom in that part of the globe.

Unlikely ally

In several ways, Japan is the exact opposite of Australia. It is one of the few Asian countries that never became a Western colony. It is closed to immigrants – a contained island universe with a distinct identity.

For most of the 20th century, there was very little interaction between Australia and Japan. Japan’s protectionist agricultural policies hindered any potential increase in agricultural exports, in particular beef, from Australia. Until very recently, most Australians had an indifferent or even negative opinion of the Japanese. But the rise of China has been shaking up existing frameworks in all of Asia.

Common interests

During the Cold War, Australia was a marginal player. There was no attempt by the Soviet Union to expand into Australasia. Nevertheless, Canberra has been harboring serious security concerns for a long time. It is aware that it cannot defend its immense coastline all on its own. Shortly after World War II, the Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS) was created as an American security guarantee for its remote ally.

Like Japan, Australia could be threatened with invasion by powerful neighbors. Currently, although the bilateral relations between Canberra and Beijing are in a trough, there seem to be no immediate Chinese designs on Australia. But recent geopolitical shifts in Asia have affected both Japanese and Australian security interests.

Since Tokyo emphasizes renewable energy, it is certainly not a prime target for Australian coal exports.

The most important legacy of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is that he enhanced Japanese international presence. This was especially evident in his special relationship with U.S. President Donald Trump, but he also substantially increased Australian relations with Japan and their involvement in Southeast Asia and India.

Dark shadow

In recent times, China has been aggressively promoting its socioeconomic model. Instead of free trade, liberal democracy and the rule of law, China proposes authoritarianism, mercantilism and a strong emphasis on public order. Beijing uses these designations in a sense that does not correspond with their traditional Western understanding. China’s president and communist party leader Xi Jinping promotes himself as a champion of globalization and free trade, while in reality, China pursues these goals through its peculiar vision of protectionism and barter trade.

Most of China’s rise to power has been achieved in the economic field. This happened between the late 1970s and 2012, when Mr. Xi came into office. Since then, not only Chinese rhetoric but also policy has become more warlike. This change results from a more confident leadership style, clearly freed from the cautious pragmatism of Deng Xiaoping (1978-1989).

Facts & figures

Most notably, Sino-Australian relations have deteriorated significantly over the past three years. Canberra irritated Beijing by being the first Western country to ban Huawei’s 5G network. It also asked China for an inquiry into the origins of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak. There was sharp Australian criticism of interventions into Hong Kong affairs and complaints about the treatment of the Uyghur minority.

Beijing reacted swiftly and harshly. The Chinese hit the Australians where it hurt most by banning substantial Australian exports such as coal, wine and cotton. The move was also intended as a warning to other countries. Australia was an easy target, as it has a substantial surplus in bilateral trade with China – by far the biggest market for Australian exports. The Japanese market comes at a distant second. Since Tokyo emphasizes renewable energy, it is certainly not a prime target for Australian coal exports.

Quadrilateral dialogue

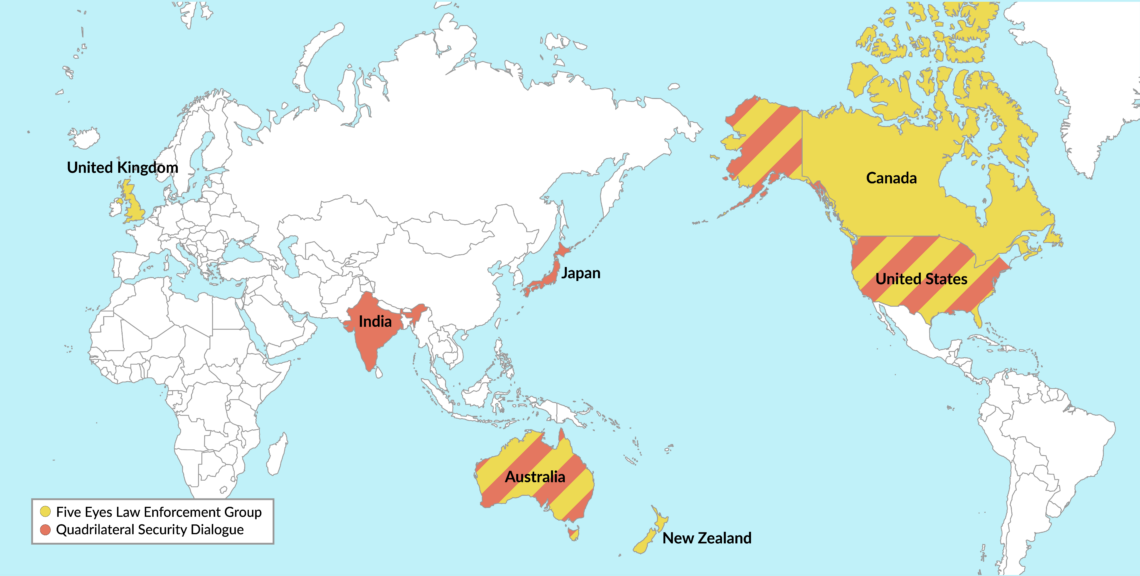

In recent years, the threat of Chinese bullying has brought major seafaring and democratic nations together. Australia, India, Japan and the U.S. have come together to coordinate their defense and security policies. The new operation is known as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad). It is still a young organization, although Chinese leader Xi Jinping has already denounced it as an Asian NATO. Obviously, China sees much potential in this forum.

The four nations involved all have a strong naval tradition. The U.S. remains, of course, the paramount maritime power in the world. India has a much longer naval tradition than China. Many experts still see Japan as Asia’s most effective navy, with operational qualifications far surpassing those of the Chinese Navy, even if it does not have the same material strength.

Scenarios

In East Asia’s recent history, the Trump presidency was a watershed. It was during Mr. Trump’s tenure that Japan’s security establishment realized it had to substantially reduce its dependence on the U.S. This was not only due to financial pressure, but more importantly, the result of growing doubts about the reliability of unconditional American support in case of a crisis or a war. These concerns became especially salient because of the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, which China claims, There are also worries that Beijing could have its eye on Okinawa Island.

Under Prime Minister Abe, Japan has initiated a change in its strategy, targeting security instruments beyond the bilateral treaty with the U.S. With President Joe Biden in the White House, Tokyo might feel some superficial relief. But it will likely seek other security guarantees as well.

In the context of the Quad, Australia has another asset that would fit well into a new multipolar security strategy. Canberra belongs to the “Five Eyes,” an intelligence alliance that includes the U.S., the UK, Canada and New Zealand. Japan, which has long cooperated with the organization, recently expressed its interest in joining it.

Beijing will exert considerable pressure on Canberra to keep Australian relations with Japan and other Asian nations within a limited framework. There can be no doubt that the world is entering a new kind of Cold War, with similar containment strategies at play. For the Japanese and the Australians, China has overstepped the boundaries of acceptable international behavior. Aggressive policies and diplomacy built on intimidation have done nothing to appease concerns about the long-term intentions of the Chinese.

China is betting on its “wolf warrior” diplomacy to intimidate Australia. However, for the time being, the government stands firm and Australian business leaders, who earlier on had advocated a cautious approach, are now supporting a tough line. Chinese aggression against Australia will only strengthen Japan and the U.S.’s resolve to intensify their security cooperation with Canberra.