Australia’s foreign policy pivot

In response to China’s aggressive stance in the Indo-Pacific, Australia has initiated its largest defense overhaul since World War II.

In a nutshell

- China’s latest provocations have prompted Canberra to seek allies

- The Australian government is modernizing its armed forces

- The reforms include a drastically increased military budget

The geopolitical structure of Asia is rapidly changing. Notably, most Asian countries are not able to control their security environment but are instead caught up in tensions between the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Asia is no stranger to superpower rivalry; the U.S. and the Soviet Union long competed for influence in the region, for example during the Vietnam War. But the emergence of China as a global player is creating new challenges.

After the Cold War ended, Australia, like many other Western industrialized nations, cashed in on the “peace dividend.” The West had won decisively and there seemed to be no credible military threat to Australia. There was some concern about undocumented immigrants and, at the height of Islamist terrorism, some worried about fundamentalists coming from neighboring Indonesia. But these fears never led to anything beyond policing operations.

All this has changed with the emergence of China as a new superpower and with the extended war resulting from Russia’s invasion into Ukraine. Many Asian countries have had to reassess their position vis-a-vis Beijing as well as their interaction with the U.S. This is most noticeable in Japan, South Korea, India, the Philippines and Vietnam, but the same goes for Australia. Suddenly, Canberra has to worry about its vulnerability to the Chinese threat and assess the security challenges posed by its extensive coastlines and sparse population.

Facts & figures

A new security architecture in the Indo-Pacific

Seen from afar, Australia looks like a geopolitical paradise. It is the only continent that is entirely covered by a single nation-state. Australia has no land borders with other countries. Meanwhile, China has several neighbors with whom it has unsettled border disputes. Australia’s position is much more favorable, and it has a more socially and culturally cohesive population.

For most of the 20th century, Australia had extremely close ties to the United Kingdom. It is a member of the Commonwealth, and the British monarch is the head of state. When the UK joined the European Union in 1973, it came as a rude shock to Australians. Many saw it as a betrayal. This barrier was removed by Brexit, but the decline of the British manufacturing industry had already reduced economic ties between the two countries, and there is little prospect for a substantial expansion of trade between the UK and Australia.

Due to its constitutional and political ties with the UK, Australia participated in the two world wars. Large contingents served on the side of the allies, fighting and dying in battles far from their homeland. In World War I, Australia suffered over 60,000 casualties, and in World War II some 500,000 Australian men and women served overseas. Apart from some Japanese raids, Australian territory was not touched by the war, which raged further afield in Europe, Southeast Asia and the Far East.

Some 60,000 Australians served in the Vietnam War. Already in 1951, Canberra had joined the Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS), which remains Australia’s most important international security instrument. At the time ANZUS was established, the main fear was the military threat posed by the Soviet Union and the subversion that loomed from Communist China and from neighboring Southeast Asia, especially from Indonesia until 1966.

It was in the 1990s, during the Labor government of Prime Minister Paul Keating, that Australia turned its economic and diplomatic attention toward Asia, most notably China. Under the Labor government of Kevin Rudd, Prime Minister from 2007 until 2010 as well as half a year in 2013, relations between Australia and China reached an apex, only to cool off during the Liberal governments of Prime Ministers Tony Abbott (2013-2015) and Scott Morrison (2018-2022). The strain in bilateral relations was to a large degree caused by the ideology shift under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, who took over in 2012.

Australia did not hold back on criticism about how China dealt with the Covid-19 pandemic, its dismal human rights record and the persecution of the Uighurs. As a result, it had to face Beijing’s wrath. Economic sanctions ranged from Australian coal to Australian wines.

More by Urs Schöttli

Fear of China brings Japan and South Korea closer together

The implications of a shrinking Asia

These extensive sanctions, together with the manifest aggression of “wolf warrior diplomacy,” shocked Canberra and resulted in a new awareness of the Chinese threat. Australia suddenly realized it could not limit its rivalry with China to the economic field. Trade had failed to democratize China’s political system. The new China under President Xi’s rule required a profound foreign policy shift.

Australia was not the only nation confronted with this new reality. The American position toward China moved from cooperation to containment. ANZUS alone was not enough anymore, and Australia had to seek out cooperation with other liberal democracies in Asia.

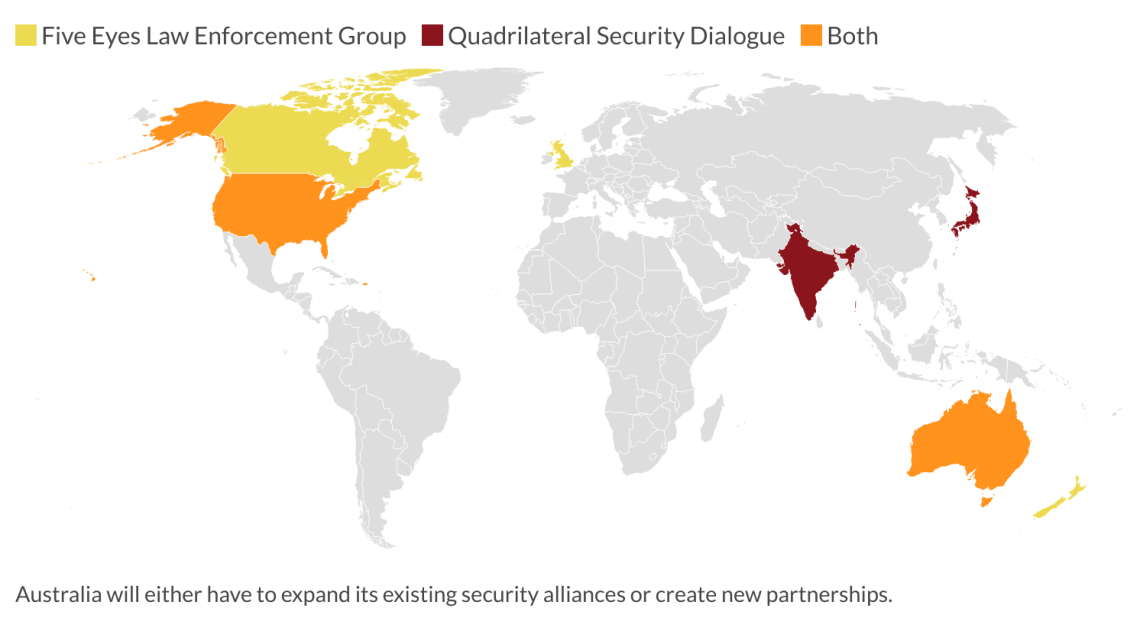

This new approach resulted in the establishment of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), comprising the U.S., Japan, India and Australia, and the launch of AUKUS, the trilateral security partnership between Australia, the UK and the U.S. As of yet, Australia is not a part of traditional military and security alliances like NATO or the bilateral treaties the U.S. has with South Korea and Japan. But there are indications that a new regional security architecture is emerging throughout the Indo-Pacific. Significantly, Beijing has already criticized these initiatives as attempts to create an “Asian NATO.”

Scenarios

The launchpad for the coming extension and enhancement of Australia’s military defense capabilities is the recently published Defense Strategic Review, the first in 40 years, hailed by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese as “the most significant work that has been done since World War II.” This review sets the stage for a series of new priorities, all aimed at recasting the mission of the Australian Defense Force in the “missile age.”

Bearing in mind the military capabilities acquired by China, Australia can no longer rely on its geographic remoteness. It has to be able to project its defense far beyond its own shores. Achieving this will require several adjustments in military hardware and operational doctrine. One crucial goal is the acquisition of up to eight nuclear-powered submarines through AUKUS. The recruitment of a highly skilled defense workforce is of equal importance. With the introduction of new weapons systems comes the need to deepen diplomatic and defense partnerships with Indo-Pacific countries.

The main scenario for the coming decades is an Australia that invests much more resources in international frameworks. Canberra must contend with the double challenge of the new-old hegemon China and, due to resource constraints, a more demanding American security policy in Asia.

Both major political parties in the U.S. will for the near future pursue a course where more engagement will be requested from allied and friendly nations. The initial shock caused by Donald Trump’s blunt admonitions will continue to loom over Asia. The tone may have become less strident under U.S. President Joe Biden, but the message has not changed.

Australia has turned more decisively toward Asia, toward the Indo-Pacific than ever in its relatively brief history. Initiatives such as the Quad and AUKUS are likely only the beginning. Looking ahead, the most probable development is either an extension of the membership of AUKUS and the Quad or the establishment of new security partnerships.

In any case, the internationalization of Australia’s foreign and security policy will gain steam. The times of a certain naivety in foreign policy are gone for good.