The Fed and ECB: Average inflation targeting for two

Central banks have long maintained that price stability means 2 percent inflation. Now the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have changed the wording to “average inflation targeting”. This seemingly small change aims to contain public debt, not inflation.

In a nutshell

- The Fed and the ECB are focused on protecting the solvency of indebted governments

- “Average inflation targeting” means higher inflation will be tolerated for undefined periods

- A combination of high inflation and low interest rates would shrink debts

Regardless of the letter of their statues, the two major central banks of the West, the United States Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, are pursuing two goals – price stability and financial solidity. They also try to promote growth: to reduce unemployment, as the Fed would put it; or to enhance EU policymaking, as the ECB would argue.

Their record is well known. During the past decade, inflation has been low, and both institutions have taken advantage of the circumstances to engage in rather generous monetary policy. Money printing and easy credit have rescued many ailing companies’ balance sheets, avoided potential public-debt bankruptcies in Europe and, more generally, fueled the illusion that crises can be softened by resorting to almost free monetary lunches. Western central bankers have ensured that most large commercial banks survived the crisis and their self-inflicted wounds, which is not quite the same as “financial solidity.” However, they have failed to meet their 2 percent inflation target, nor have they succeeded in creating sustained growth.

The commitment to ongoing easy credit raises a question about credibility and, as a result, stokes uncertainty.

The recent pandemic has made things more complicated. In particular, one wonders whether the central bankers will keep ignoring the fact that manipulating interest rates is tolerable only if it is a short-term instrument to offset the business cycle and neutralize erratic responses by some market leaders. To reassure the public, the Fed and ECB have announced that they intend to keep interest rates low for a few years.

Facts & figures

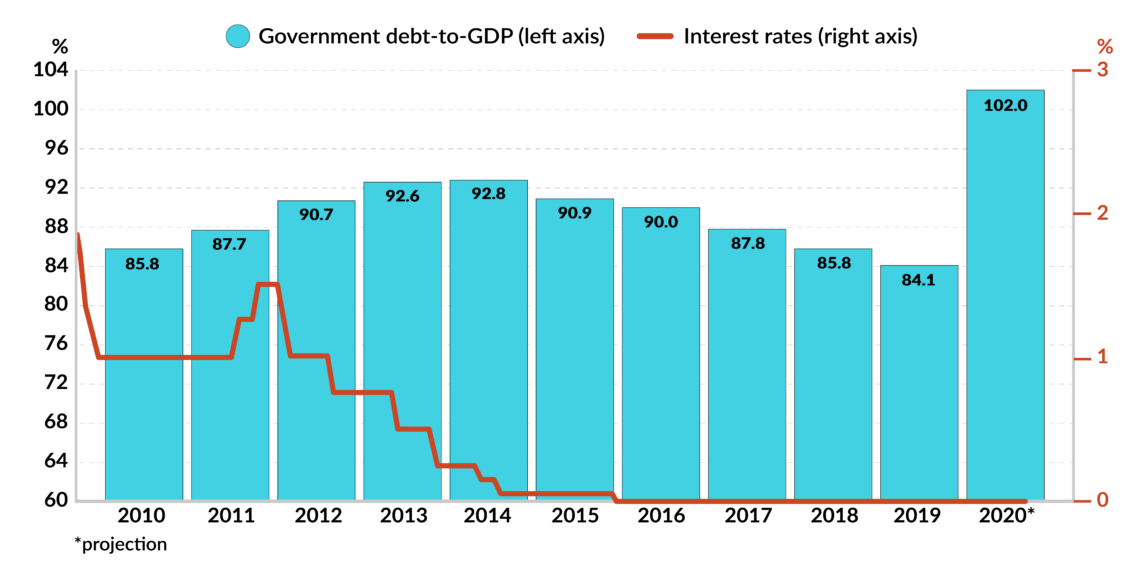

It was explained that even if they intend to use monetary policy to reach a 2 percent inflation rate, the actual target is long-term average inflation. To compensate for the years of almost zero percent inflation, therefore, the short-term target is much higher than 2 percent. While this is reassuring for easy credit advocates, it is deeply worrying for those who suffer from manipulated markets: prudent investors and pension funds, for example. Moreover, the commitment to ongoing easy credit raises a question about credibility and stokes uncertainty.

Facts & figures

In this light, different scenarios open up. This report considers three possible policy attitudes and their likely consequences.

One outcome is the business-as-usual prospect. A second one materializes if inflation eventually picks up (in August, it was 1.3 percent in the U.S. and -0.2 percent in the eurozone). A third situation features a new negative shock, such as a Covid-like emergency, or worldwide geopolitical tensions.

Reading the signals

The first scenario entails the continuation of the ongoing, loose monetary policy and nothing else. Despite the distortions it would cause, most policymakers would prefer this very scenario. Their priority is stable and artificially low interest rates, which make large public indebtedness sustainable, allow big businesses to finance their needs on the bond and equity markets at fire-sale prices, and help heavily indebted consumers. Moreover, loose monetary policy would please the EU authorities, if and when Brussels issues its own debt to finance economic recovery in Europe. Central bankers would also be happy. Within a business-as-usual framework, they take credit for stability, and their role as key economic actors would grow stronger.

In this light, there is no doubt that by pointing out that the real target is average inflation rather than point inflation, central bankers are signaling that they will keep interest rates low regardless of inflation. By sticking to average inflation targeting, both the Fed and the ECB have announced that inflation is no longer a target, that the crucial variable is interest rates and that they will do what it takes to keep them low.

Is it a credible commitment? The answer is yes, at least in the short and medium term.

Further distortions may need to occur before some backtracking is considered.

The constituencies that profit from artificially easy credit have become very large, and central bankers will not disappoint them. True, most opinion makers are right in underscoring that business as usual features plenty of distortions. Their worries are justified. It is understandable that they end up predicting rather gloomy economic pictures for the future, with geopolitical consequences of all sorts. Yet, the past decade has shown that imbalances can persist and that further, and deeper, distortions may need to occur before some backtracking is considered.

What would happen if consumer-price inflation picks up faster than anticipated? And how desirable would that be? These core questions characterize the second scenario, which is realistic for the U. S., although less likely for the old continent. The main reason for this asymmetry is that, in contrast with the prevailing American attitude, Europeans tend to consider liquidity a buffer against future emergencies (e.g., wage and pension cuts, job losses).

Will they do it?

As a result, Europeans will not take full advantage of easy credit to increase expenditure: bottlenecks and inflationary pressures will therefore be modest. Significant inflation is a realistic prospect only in the U.S., which probably helps explain the recent announcements by the Fed. Will the Fed keep its word?

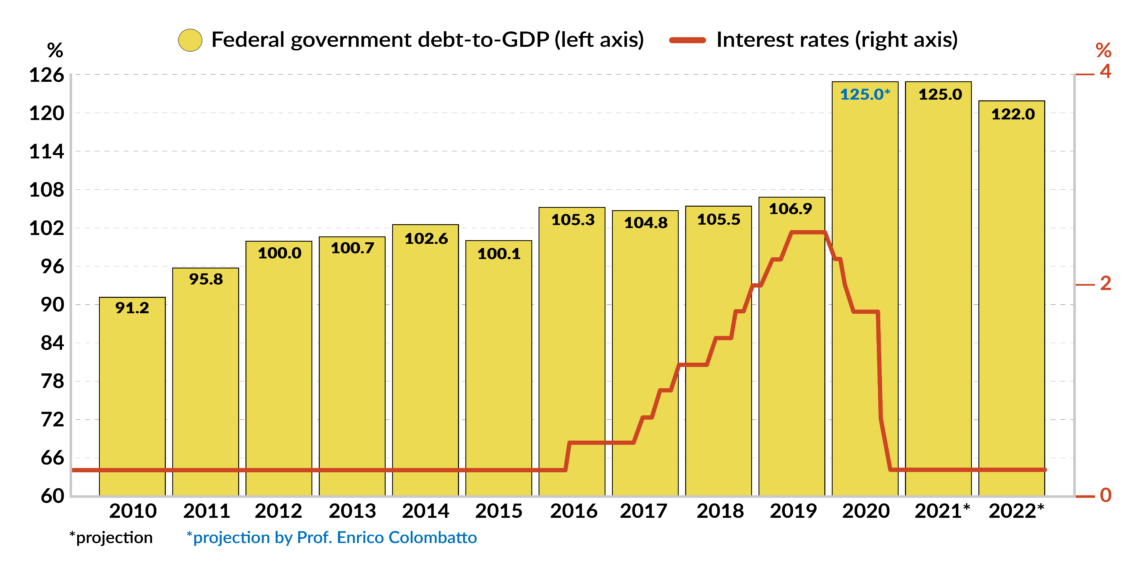

We trust it will. Although the Fed’s statutory missions are price stability and maximum employment, the Fed’s current policy goal is downsizing the American federal net debt, which amounted to 61 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011 and 77 percent in 2019. It is expected to exceed 100 percent by the end of this year and rise further in 2021. (Federal net debt is gross federal debt minus the debt that the federal government has sold to other governmental organizations – agencies and the Fed. In other words, net is the debt held by the public.) A combination of high inflation and low interest rates means that the debt’s real size drops and that debt servicing remains low. This scenario would be the ideal from the Fed’s perspective and explains why its commitment is credible.

Scenarios

Of course, this raises one central question: who will buy American treasuries once they offer a negative real interest rate? The answer depends on whether the dollar remains the dominant reserve currency globally and whether financial investors will consider American treasuries a haven, not unlike what has happened to the German Bund in years past.

Interest rates will remain low if other worldwide shocks occur, and policymakers feel obliged to save the welfare state, expand public expenditure and keep public debt sustainable. This scenario applies to Europe in particular. However, low interest rates and easy credit will be useless if nobody is willing to borrow. If so, we might be heading toward a new and somewhat disturbing picture.

If production drops and bottlenecks emerge, the West will be facing inflation, spiraling public debt, negative real interest rates and plenty of financial bubbles. Central bankers will run to the printing machines, issue new paper currency, buy treasuries and allow governments to spend all that it takes to buy consensus. Our monetary systems’ credibility would come under severe pressure and discretionary public expenditure would probably lead to fresh and disquieting tensions.

Average inflation targeting by the two major Western central banks has little to do with price dynamics. Instead, it is a way to announce public-debt targeting while pretending that both institutions comply with their statutory target: price stability.

There is a difference in emphasis, however. The Fed aims to keep the U.S. public debt burden under control and eventually bring the debt-to-GDP ratio well below 100 percent. By contrast, the ECB strives to keep public-debt servicing low, hide a structural decline in the economic growth rate and make it feasible for its member countries to sustain large budgetary deficits for at least two more years. This goal explains why average inflation targeting is a credible promise, especially in Europe, and why financial markets had better brace for more uncertainties and bubbles.