India nudges China toward Belt and Road changes

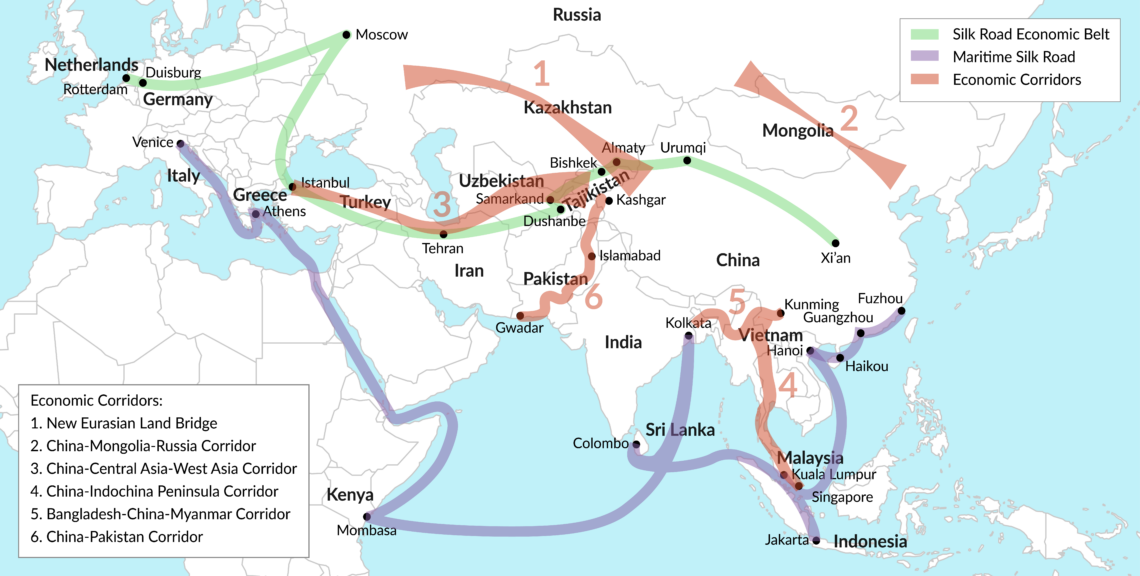

India has long warned of the strategic dangers posed by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Today, many countries are voicing suspicions about the BRI’s potential effects. The project also faces difficulties due to financial problems within China. Beijing seems to be recasting the BRI as a more open project.

In a nutshell

- India has succeeded in turning international public sentiment against the BRI

- China also has its own domestic problems hindering the project

- Beijing will have to refocus the initiative on a smaller set of strategic goals

- The projects that most threaten Indian influence are unlikely to be scrapped

One of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s successful foreign policy initiatives has been to shine a light on the negative aspects of China’s huge Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure project. Beijing has long touted the BRI as a global public good, and in 2017, India was alone in arguing that the BRI was ensnaring smaller countries in debt to further China’s geopolitical interests. Today, most major Western powers share New Delhi’s view.

BRI projects are now a source of controversy across the world. In September 2018, Malaysia’s government canceled three key parts of the BRI’s Southeast Asia corridor. Most significant, however, has been the United States’ newfound hostility to the initiative.

India’s goal is to carefully push the Chinese toward accepting global norms of transparency and sustainability when building overseas infrastructure. It wants the BRI to be guided more by commercial considerations than strategic ones. This is one reason India is the second-largest contributor to China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and a partner in the New Development Bank, the so-called “BRICS Bank.” Both follow the same funding rule book as mainstream multilateral financial institutions like the World Bank.

Yet the AIIB and the NDB are minor players when it comes to BRI funding. Together they have loaned just over $3 billion to BRI-related projects. In comparison, by 2016 the state-owned China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank had jointly lent or made equity investments of over $200 billion to support the BRI.

International backlash

Three developments are moving Beijing to reluctantly “normalize” at least some of the BRI’s financing. One has been the intense international backlash – a fairly recent phenomenon. In 2016 India was lectured by White House and State Department staffers on the need to “be more flexible” about the BRI. The U.S. privately argued that the $65 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the BRI’s flagship project, would help stabilize Pakistan. Japan, whose corporations dreamed of large contracts, was circumspect. Europe was an enthusiastic cheerleader for the Eurasian corridors. Even within the Modi government, say officials, opposition to the BRI was originally limited to “two and a half people” – but one of them was the Indian prime minister himself.

Thanks in part to noise generated by New Delhi, Sri Lanka’s debt to China was a cause celebre in international media.

By the summer of 2017, the tide had changed. Thanks in part to the noise generated by New Delhi, Sri Lanka’s huge debt to China was a cause celebre in international media. Chinese interference in the domestic affairs of countries that had received BRI funding, whether Hungary, Zimbabwe, Laos or Cambodia, began to ring alarm bells. Beijing did not help by ensuring contracts went exclusively to Chinese firms. The Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) concluded in January 2018 that only 11 percent of BRI contracts had gone to foreign firms. Japan, France, Germany and Britain have come out openly against the BRI in the past two years.

Today, Washington is the most strident opponent of the BRI. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo described the BRI as a “predatory economic activity.” A senior State Department official said the projects were “made in China, made for China.” At the APEC summit in November 2018, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence took a swipe at the BRI in a speech that was marked by strong criticism of China: “The United States deals openly, fairly. We do not offer a constricting belt or a one-way road.”

Privately, the U.S. has wagged a finger at countries in Central Europe, Southeast Asia and the South Pacific that have embraced Chinese funding. The U.S. Congress recently passed the BUILD Act, which puts together a $60 billion fund (managed by the International Development Finance Corporation) to provide alternative infrastructure and promote World Bank standards in other countries. As a State Department official told me, “Many poorer countries don’t have the capacity to enforce World Bank standards and the BUILD Act is designed to help them.”

Beijing blames New Delhi for much of the bad press the BRI has received.

Beijing blames New Delhi for much of the bad press the BRI has received. The state-owned Global Times published an editorial denying China was practicing “creditor imperialism” and said the phrase was “created by India.” Chinese diplomats have privately told their Indian counterparts that they had “underestimated [India’s] opposition to the BRI’s impact on the rest of the world.”

Public view, financial difficulties

A second important development has been the Chinese public’s tepid response to the BRI. Given Beijing’s iron hand on the media and internet, a genuine picture is hard to determine. When Chinese President Xi Jinping announced billions of dollars for developing countries, the reaction on Chinese social media was negative. In a radio interview, retired professor Sun Wenguang said, “Regular people are poor, let’s not throw our money away in Africa.” Just as he was saying those words, Chinese police entered his home and arrested him. There has been other criticism by academics and journalists worrying that China had become a “flashy big spender” overseas, wasting money on loss-making “image projects.”

The third, and arguably most important, development to work against the BRI has been China’s own domestic financial problems. The BRI is becoming increasingly unaffordable. China is experiencing remarkable capital flight, about $3.8 trillion over the past decade, and has seen its enormous foreign exchange reserves fall by nearly a quarter over the past four years. More worrying has been the enormous debt built up within the Chinese economy. The ocean of credit that fueled so much of its recent growth has begun to generate a variety of illnesses, including stock market and real estate bubbles, and bad loans in banks. Simply put, Beijing no longer has as much cash to spend overseas, especially when it is not generating a profit.

As recent roadshows in Hong Kong and elsewhere indicate, China has begun canvassing outside investors to bail out BRI projects. The flip side will be the acceptance of the sort of financial norms that India and other countries have been advocating.

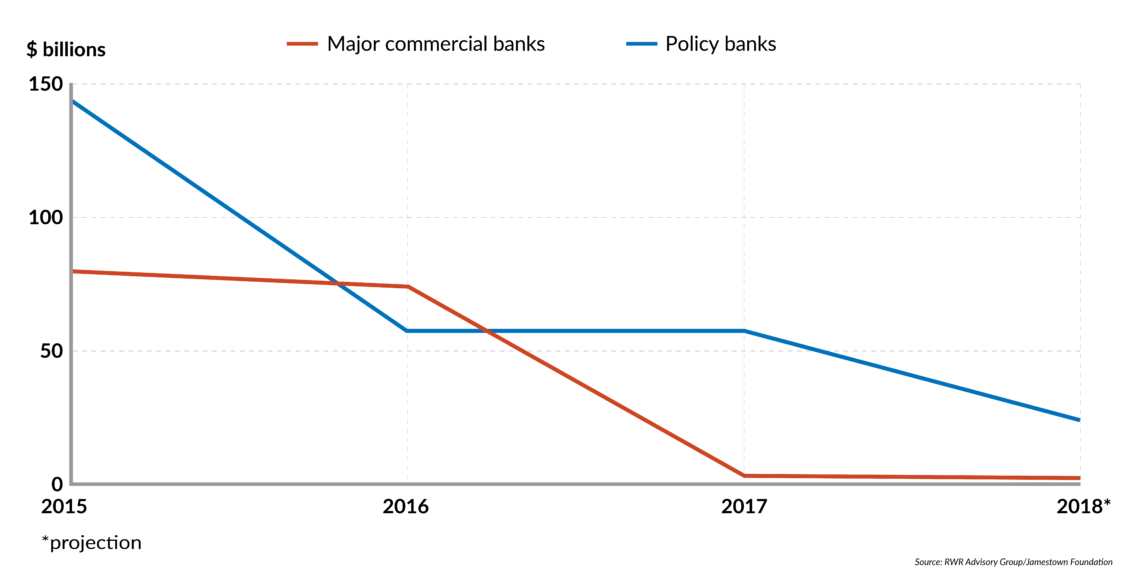

Several public and private studies, either by tracking thousands of individual BRI projects or measuring such indices as Chinese capital goods exports, have concluded that Chinese funding for BRI projects has fallen by between a third and a half over the past two years. Chinese commercial bank lending has dropped off unusually sharply.

Facts & figures

Funding drop

BRI lending: policy banks vs. major Chinese commercial banks

Advisors to China’s policy banks (those established specifically to implement the government’s economic policies) say Beijing is quietly beginning to prioritize BRI projects. Only a handful of them will continue to receive financial support for noncommercial reasons. The rest will have to find external partners. Some may be abandoned. Japan, which shares India’s desire to push the BRI toward more transparency and sustainability, is already holding out a financial carrot. During a state visit to China in late October, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe offered to back BRI projects, so long as they fell in line with global standards.

Scenarios

So far, China’s financial difficulties regarding the BRI are in line with the Indian government’s internal analyses. However, the Modi administration recognizes that the elements of the BRI it is most concerned about – CPEC and other Indian Ocean projects – are also the ones most likely to survive any review. China will not shy away from mixing military and diplomatic goals with these projects.

What can be expected next is the evolution of a smaller, smarter BRI with a sharper strategic focus. This would at least reveal which roadbuilding activities are actually about empire building. It is likely Beijing will simply push ahead with these core projects, calculating its ability to economically shock and awe local regimes will be enough to let it plant its flag where it wishes. New Delhi, Tokyo and Washington are in rough agreement that the most important battleground right now is Southeast Asia.

A second scenario revolves around a concerted international response to the new BRI format. There are several geopolitical triangles and quadrilateral groupings that want to influence events in Asia, some of which include European countries. Which, if any, will coalesce into genuine multilateral bodies depends on a few developments: the degree of Chinese assertiveness, whether the U.S. can reassert leadership and the domestic choices of countries like India, Japan and Indonesia. BRI alternatives could become a reality.

A final scenario depends on whether Beijing’s economic miracle really starts to sputter. China has defied many predictions of economic crisis. Chinese economists do not deny there are problems, but assume Beijing has the resources to solve them. If China stumbles and experiences a genuine recession, the BRI may find itself starved of cash and consigned to the dustbin of history.