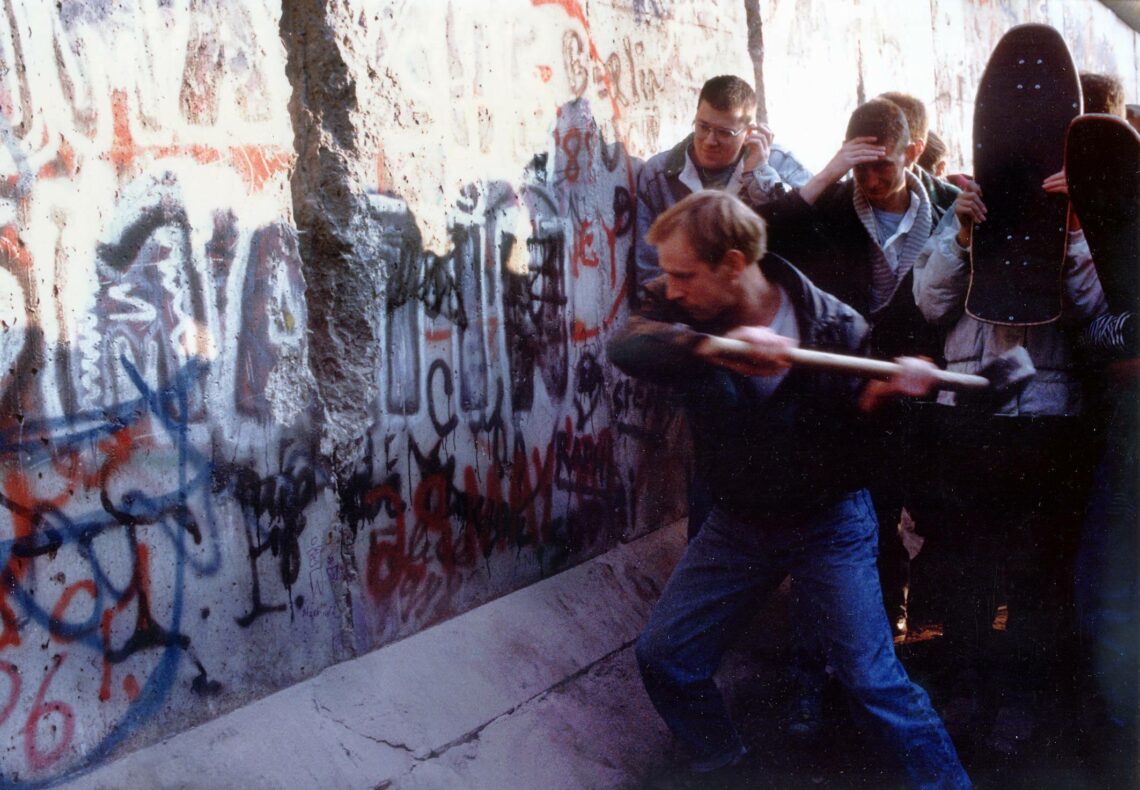

Germany 30 years after the Berlin Wall came down

A little over 30 years ago, the Berlin Wall came down. GIS expert Michael Wohlgemuth, who studied in both East and West Germany in the late 1980s and early 1990s, shares his impressions of how far the country has come economically, and the challenges it faces as a deepening political divide threatens three decades of progress.

In a nutshell

- Germany’s economy benefited from the fall of the Berlin Wall

- Three decades of political complacency have followed

- A political divide threatens Germany’s economic model

“Where were you the evening of November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down?” Nearly all Germans (and many others around the world) over the age of 40 can answer that question. It was certainly the most important and cheerful event in postwar German history.

As for myself, that evening, I was in my student apartment in Freiburg, West Germany, reading Friedrich Hayek, the classical liberal economist. I was not studying his early predictions of the collapse of socialism, which would have been more appropriate for the occasion, but rather his complex work on business cycles on which I was to write my master’s thesis. As I watched the breaking news on television, I was in tears, like so many other Germans in Freiburg, Berlin or elsewhere.

I still wonder how Hayek himself received the news from Berlin. At the time, he was also living in Freiburg but was in poor health at the age of 90. His last book, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism, had just been published the previous year. Like many of his other writings since the 1930s, that book predicted the economic, political and moral decline of socialism. It had been ignored and attacked by mainstream social scientists and intellectuals, especially in Germany and in his home country of Austria.

Surprise, surprise

The decline of socialism came as a surprise to most mainstream economists, politicians and pundits. In the mid-1980s, East German statistics purported to show that the country was the 10th-strongest industrial nation in the world. Many experts in the West believed those figures. If you measure output in tons of steel, in the number of cars (with chassis made of Duroplast, a form of plastic containing resin strengthened by recycled wool or cotton), or in square kilometers of (ugly) wallpaper, East Germany did produce quite a lot.

Socialism produced more environmental damage and human misery than added value and human dignity.

Yet without the measuring rod of global market prices, one cannot know what output will be worth once consumers are free to choose and producers are forced to compete across borders. That was the basic truth that German pundits learned only after the wall came down.

East Germany was effectively bankrupt many years before 1989. It could no longer service its growing external debt, not even by selling visas (both for entering and leaving the country), works of art or even the freedom of its political prisoners to the West German government.

Its state-monopolized, planned industrial sector was rapidly decaying due to a lack of investment, innovation and entrepreneurship. Socialism produced more environmental damage and human misery than added value and human dignity. It is no accident that with the advent of the Hayekian “knowledge economy,” the decentralized free market took a clear lead. The centrally planned economy, with its innate frustration of individual freedom and private initiative, proved to be a fatal mistake.

Communism’s devastation

Later, it became clear to me just how bad the economic situation in the former East Germany was. In 1992, I left cozy Freiburg and joined the pioneers founding the first Max Planck Institute for Research into Economic Systems as a PhD researcher in the former East German town of Jena. The University of Jena, founded in 1588, can claim great names among its former students, visitors and professors, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Alexander and Wilhelm von Humboldt and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. It is the same town where Carl Zeiss and Ernst Abbe founded a world-famous firm manufacturing optical instruments in 1846.

When I arrived in Jena, I was shocked. Most people lived in ugly prefabricated buildings and the old city center, with its once-fabulous market square, was now a stretch of wasteland turned into a parking lot. Its medieval structures survived both the 1806 Battle of Jena-Auerstedt in which Napoleon defeated the Prussian army and the 1945 bombings of World War II. But those buildings did not survive East German town planning in 1968: the place was flattened and renamed Cosmonauts’ Square to offer space for tens of thousands of commandeered workers to see Yuri Gagarin on a special day off.

Still, I soon felt quite at home in this part of unified Germany. Although many people lost their jobs or were put in state-funded training programs, I could feel their genuine pride in the city’s pre-communist history and their real willingness to restore it. Perhaps not by accident, they even elected a mayor from the FDP, a classical liberal party.

In 1994, the German Economic Association had its annual meeting in Jena. Many of my colleagues were presented with some inconvenient truths by the keynote speaker. It was Lothar Spaeth (1937-2016), the former conservative minister president of the state of Baden-Wurttemberg and then the CEO of Jenoptik, formerly Carl Zeiss, which even during communist times was regarded as a showcase of enduring technological leadership.

I remember Spaeth telling many stunned members of the audience something like this: Of course, the company can only survive with massive state subsidies, but we are using them to completely reinvent Jenoptik. For the moment, this means developing new products and production chains from scratch. We had to lay off thousands of workers. We need to retain the rest of the workforce, but at the moment must keep them away from our factory gate. If they started producing the old products, our losses would balloon, since raw material and energy costs would be added to the labor costs.

Unstable politics

Since then, Jena has once again become a model city, at least by East German standards. It has successfully developed innovative industrial clusters cooperating with many research institutes and the university. Even the old Cosmonauts’ Square (later renamed Eichplatz) has become more amicable.

The political divide between East and West seems to have increased and favors the extremes on the political spectrum.

Yet at the same time, the state of Thuringia, where Jena is located, has become politically unstable. For the last four years, it was governed by a coalition led by the successor to the former East German Communist Party – the radically leftist Die Linke, which advocates the expropriation of landlords and businesses. Its coalition in Thuringia includes the social democratic SPD party and the Greens.

This coalition lost its majority in elections in October, only because the radical right-wing party Alternative for Germany (AfD) came in second. Together, the radical left and the radical right have a majority in this part of Germany. The two parties in Germany’s “grand coalition” at the federal level – the center-right CDU and the SPD – only won 22 percent and 8 percent of the vote, respectively. That is less than the 31 percent gained by the radical Die Linke alone.

Deepening divide

None of this is to say that German unification was a failure. Like almost all Germans, I still celebrate the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall every November. But it seems that 30 years on, some sobering observations must be made. While all of Germany prospered economically over the last three decades, the political divide within the country – especially between East and West – seems to have increased recently. That split favors the extremes on the political spectrum.

Now, after years of economic tranquility and political complacency, Germany is set to enter a (likely mild) recession. The big question is whether statesmanship will prevail, allowing the country to defend its socially inclusive model of a market economy.