Foreign trade – clouds on the horizon

German trade statistics are sagging. Most commentators attribute this phenomenon to the global business cycle. More likely, today’s figures are the outcome of earlier decisions made by German companies to move resources outside of Europe, and they are now developing their products elsewhere.

In a nutshell

- Indicators show German companies are investing abroad

- This will mean slower growth in Germany and Europe

- German firms will become more vulnerable to global turbulence

GIS’s Focus Germany series examines key issues facing the European Union’s most crucial member and the continent’s economic powerhouse.

Germany is the world’s third-most powerful player in foreign trade. It is a major supplier of high-quality goods and services for most economies and a very significant buyer in a variety of industries. During the 2013-2017 period, however, its exports and imports grew at an average rate of 3.7 percent and 4.3 percent, respectively: faster than Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP), but slower than world trade.

Over the past year and a half, the picture has become darker. On one hand, due to slow growth in the European Union, Germany’s exports to the old continent have stagnated. On the other hand, the Chinese slowdown is starting to take its toll. While German sales to markets outside of Europe continue growing, they are losing momentum. The same applies to German GDP. Its annual growth rate was close to 3.4 percent in early 2018 but dropped to 0.4 percent by mid-2019. Nobody expects a quick rebound. The bad news is that European exporters will find it more challenging to sell their products to Germany. The good news is that Europeans have now stopped whining about Germans’ unwillingness to share the benefits of growth with the rest of the EU. Yet, are there any negatives for Germany?

No quick fix

In previous reports, we have pointed out that the German economy faces two problems that do not have a quick fix: a tight labor market and no productivity growth over the past five years. A low unemployment rate (3.1 percent) is good news for German workers (they should expect rising salaries) and for public expenditure (there should be less pressure on the welfare state and redistribution).

It seems that German companies are ready to hire, but they are not desperate to do so.

However, the shortage of workers has driven up neither the number of unfilled vacancies nor wage rates. That suggests the demand for workers – including skilled workers – is not particularly strong. It seems that German companies are ready to hire, but they are not desperate and are not willing to go out of their way when negotiating remuneration.

Meanwhile, the stagnating productivity means that either the quality, skills and effort of German workers are not rising, or that the machinery to which they have access is not much better than in the recent past.

The data show that during the past 10 years, investment by German companies has risen at an average annual rate of about 2.6 percent in real terms, which is significantly faster than in the European Union (about 1.0 percent), but a little slower than in the United States (about 3.0 percent). Such a relatively high rate of investment with stagnant productivity and a slowdown in GDP growth seems to suggest that German companies are not engaging in significant efforts to expand their facilities or improve their technological level at home and are moving their efforts abroad.

Investing abroad

Assessing what German entrepreneurs are doing abroad – say, in Asia – is difficult. Yet, one may note that today, German foreign investments are about 100 billion euros a year, which is a considerable portion of Germany’s total annual investments (about 700 billion euros). We predict that this portion will increase unless major geopolitical disruptions occur.

Facts & figures

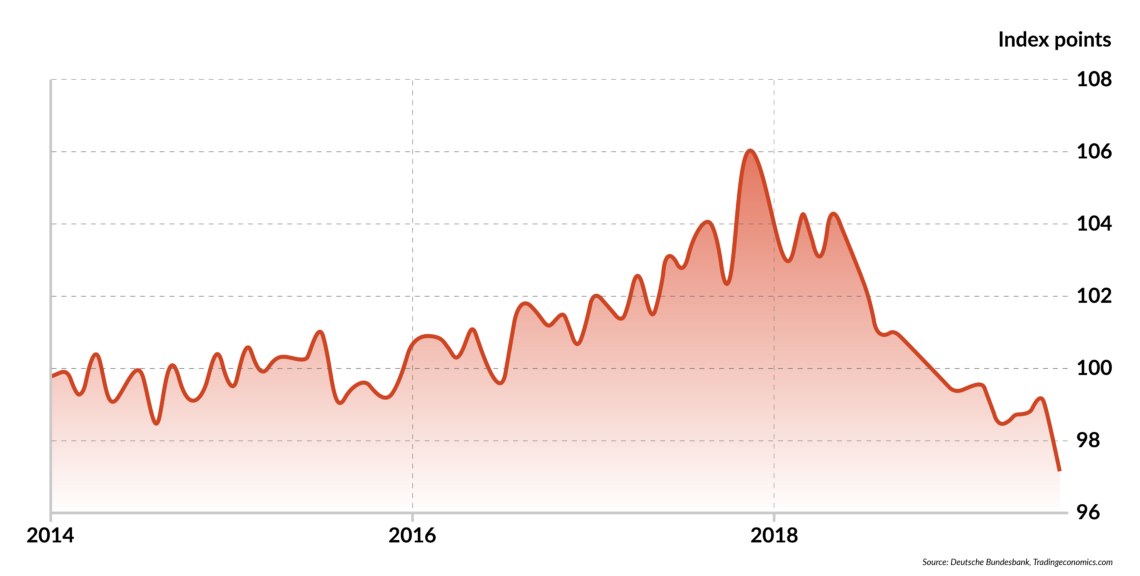

German productivity: Downward momentum

This behavior is understandable. It may follow from German entrepreneurs believing that producing in Germany may be essential to serving the European market, but that worldwide competition requires locating more production facilities where labor costs are lower, and taxation and regulation less hostile.

This hypothesis suggests that German businesses believe that the technological answers to global competition will not come from Europe. They also think it pays to develop new production arrangements – facilities, organizational and communication structures – overseas, and possibly train human capital in other countries, where the cost is lower and the productivity gains more promising.

If confirmed, these strategies would disclose rather disheartening scenarios for the future of the German economy and Europe.

Doubting Europe

Commentators usually look at the data, draw attention to critical issues and develop possible solutions. We take a different view and suggest that the data we observe are the result of crucial decisions made consciously, and which are unlikely to be reversed soon unless major shocks occur. Let us examine what this could mean for Germany and what kind of disruptions could shape a different picture.

We assume that German industry doubts whether Europe – and the EU in particular – will be the ideal location to invest in technology and engage in long-term entrepreneurial undertakings. In particular, since productivity is a combination of skills, motivation and technological endowments, German entrepreneurs are aware that today’s competition is a race in which motivation (determination and ambition) and institutional stability are the ingredients for success.

Demand for German entrepreneurs’ innovative products will be met by producers outside Germany.

If one has long-term plans, intensively training aspiring workers can create a skilled labor force relatively quickly and justify large investments in new technologies. German business believes that this vision can only be implemented far away.

This attitude does not mean that Germany and Europe will stop being productive or go into reverse gear. Instead, it means that the room for improvement is modest, that experimentation will continue taking place elsewhere and that producers outside Germany will meet ever-larger portions of the fast-growing demand for German entrepreneurs’ innovative products. Unless major changes occur in the German labor market or political instability in the rest of the world becomes dominant, this phenomenon will not disappear soon.

Weaker engine

We shall then have slow economic growth in Germany (productivity will remain all but stagnant) and increasingly strong trade relations between Germany and non-European counterparts. In the short run, German trade flows will be dependent on worldwide trends. In the long run, they will depend on the Germans’ ability to train the labor force they need – say in China, India or Vietnam – and on the attitude of the authorities in the host countries.

Within this framework, Germany will remain the EU’s core member from the economic and political standpoints. However, its ability to pull the rest of Europe forward (or slow it down) will be weaker.

German importers will probably rely more and more on German exporters based in the rest of the world.

Europe will suffer in two respects. First, because the German economy has always been the major market for European exports and possibly the saving grace for those producers who shy away from global competition. This safe harbor will no longer be there: German growth will be modest, and German importers will probably rely more and more on German exporters based in the rest of the world, rather than on European exporters.

Second, if Germany’s soft landing leads to a loss of prestige and to poor fiscal discipline in a vain to attempt to revive growth, tensions will increase within the EU. The drift toward stagnation driven by overzealous environmental policy and the illusion of social justice – within a hyper-regulated institutional context – will be irreversible.

Scenarios

The above is not the only possible scenario. More can go wrong. For example, rising protectionism would certainly harm growth and prosperity for the entire world, but especially producers and investors who depend heavily on global trade flows and could be caught off balance if they have operations in the wrong location.

The other major threat is institutional instability. Most countries welcome foreign investments and refrain from increasing corporate taxation. However, not many countries resist the temptation to intensify regulation, tamper with the price structure or manipulate the money market, even in the absence of political shocks. Changes in the quality and ideological propensities of the judiciary and of the public at large also have consequences – for example with regard to contract enforcement and to the attitude toward in-house training, respectively.

Should this happen, those entrepreneurs who took chances and walked away from regulation, taxation, and not-so-motivated cohorts of workers at home will be in deep trouble. Germany will suffer even more, and so will Europe.