Shadow over Brazil’s oil production outlook

Experts forecast a considerable growth of oil supply in Brazil, but similar predictions turned out to be overly optimistic in the past. The Brazilian government would need to remove regulations that discourage oil companies from investing.

In a nutshell

- Brazil’s pre-salt oil production holds enormous potential

- Flawed government policy turned the latest licensing into a disappointment

- A more business-friendly approach could turn things around for Brazil

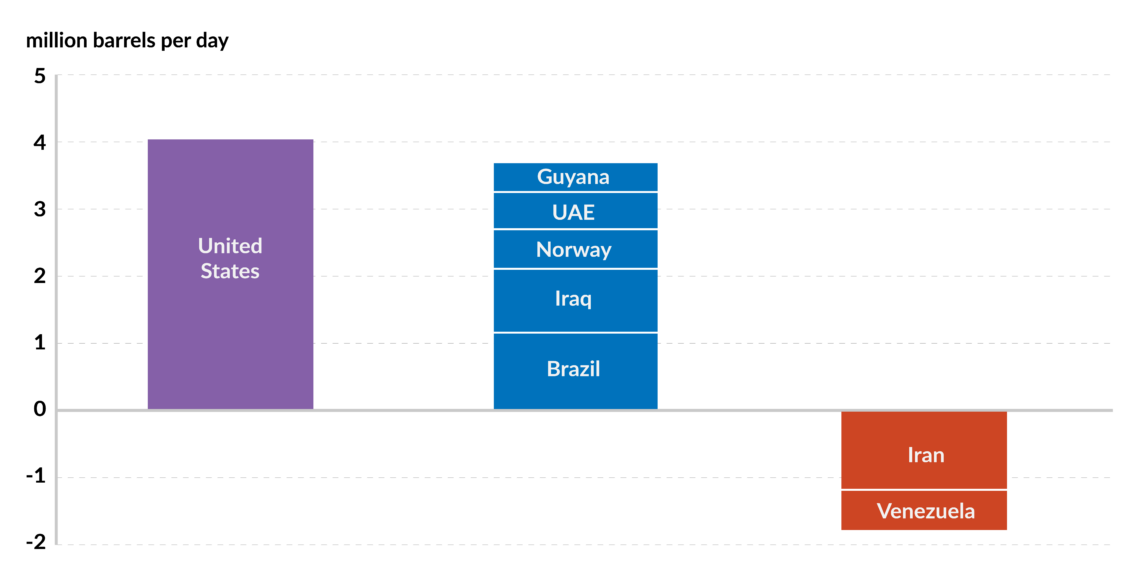

Brazil is expected to be one of the most significant sources of oil supply growth in the next five years, along with Canada, Guyana, Norway, and the United States, in addition to OPEC members Iraq and the United Arab Emirates. Brazil owes this capacity to its pre-salt layers, which have been driving production growth. Pre-salt is found in deep-sea areas and under thick layers of salt – sometimes as thick as 2,000 meters.

However, such forecasts have previously proven disappointing. A combination of above-ground factors, including market conditions, government policies and corruption scandals, has reduced the attractiveness of the below-ground resources for international investors, and the recent pre-salt auctions were a flop. Unless the government revisits its regulations and contractual terms, Brazil risks shattering its oil production ambitions, despite its potential.

A major non-OPEC player

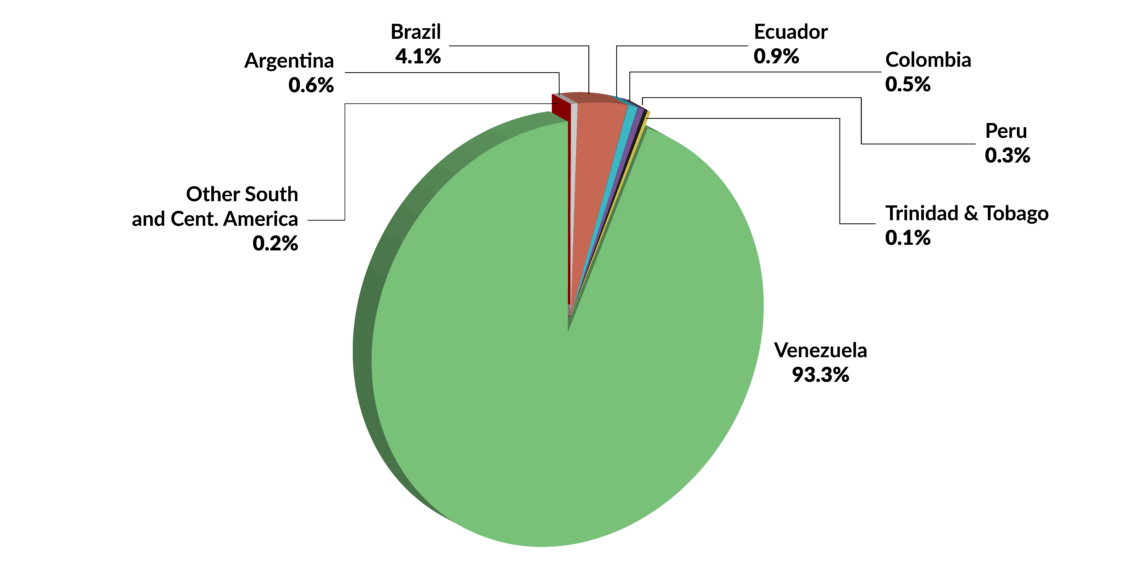

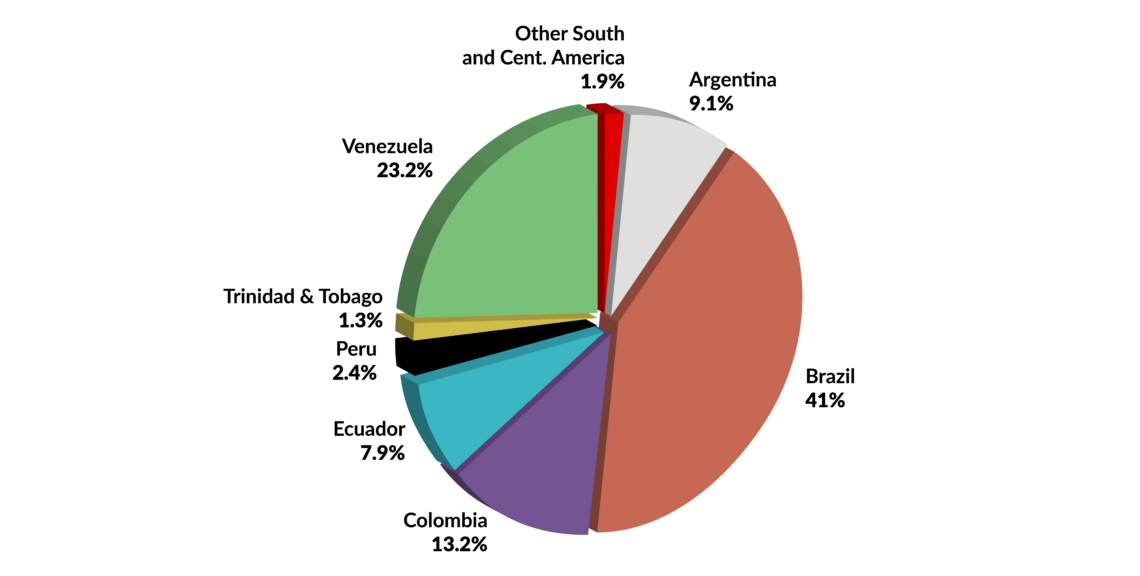

In Latin America, Brazil’s proven oil reserves are dwarfed by Venezuela, which sits on the world’s largest reserves, while Brazil ranks 15th in that respect. However, Brazil – the largest producer in Latin America – has been much more successful in converting its reserves into production, and the latter is increasing. In contrast, with output in free fall, Venezuela is a textbook example of how a government with resources can blunder with greedy and misguided above-ground policies.

With 2.68 million barrels per day (mb/d), Brazil is currently the fifth-largest oil producer in the world outside OPEC, after the U.S., Russia, Canada, and China.

Facts & figures

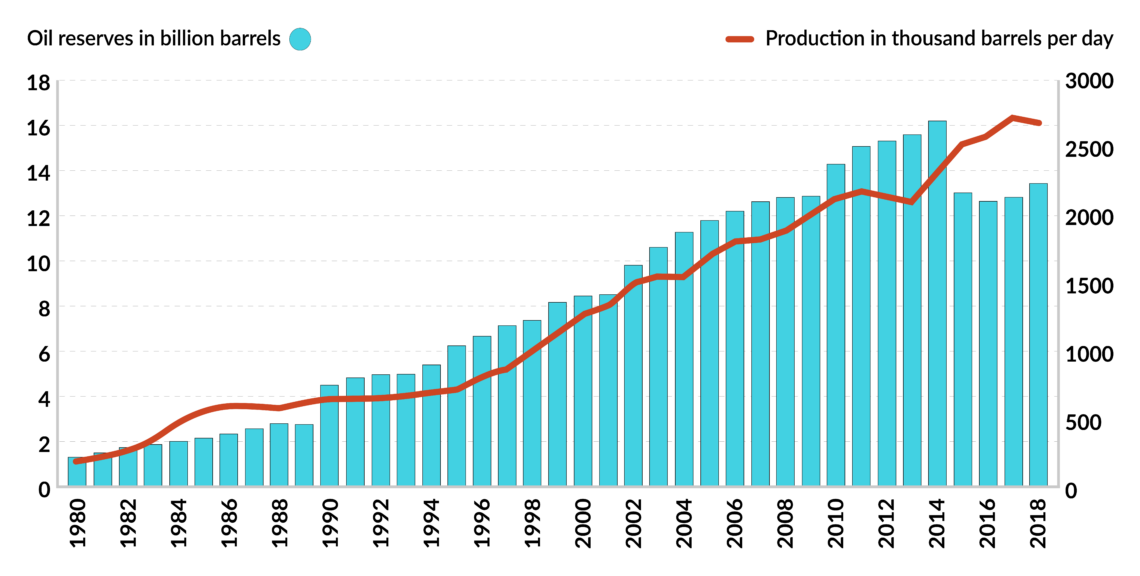

Production in Brazil has been fueled by the pre-salt fields, which have more than compensated for the decline in the country’s other production areas, namely conventional offshore and onshore.

Home to the largest offshore oil discoveries in the last decade, pre-salt production has increased nearly threefold in four years, reaching 1.5 mb/d, more than half of Brazil’s total output. According to Brazilian regulator National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP), the pre-salt region will “be responsible for the largest contribution of non-OPEC production growth in the decade to come.”

Facts & figures

Oil in Brazil

- Brazil’s oil reserves are distributed as follows: 51% in pre-salt, 42% in conventional offshore and 7% in onshore

- The geological success rate in the pre-salt is around 46%

- Currently, 10 fields are producing from pre-salt layers in Brazil

- Pre-salt wells are highly productive, producing 17 thousand barrels per day, 10 times more than the average production of the post-salt play

- Most pre-salt production has come from the Lula, Sapinhoa and Baleias Cluster fields

- Petrobras holds over 86% of the crude oil sector. Other players in the oil sector of Brazil include Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, Repsol, BP, Anadarko, Statoil, BG Group, Sinopec

Aggressive strategy

Following the discovery of the first giant pre-salt Lula field in 2006, the Brazilian government suspended licensing rounds for five years (2008-2013) to revamp regulations. The pre-salt resources required a new regulatory system that better reflected their lower exploration risk and higher production potential.

A new fiscal regime was therefore devised – the so-called Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) – with tougher terms than the conventional concessionary system that applies in the rest of the oil sector. In 2010, new legislation giving Petrobras a minimum 30 percent stake in all pre-salt operations was introduced. In 2013, another state-owned company was established – Empresa Brasileira de Administracao de Petroleo e Gas Natural S.A. – Pre-Sal Petroleo S.A. (PPSA) – to manage all PSAs. Any foreign company wishing to drill in the area would have to partner with Petrobras and PPSA.

In 2016, the government embarked on a new oil and gas strategy.

Such a move was a departure from the private-investment-friendly policy orientation of previous years. In 1997, Brazil passed the Oil Act, which ended Petrobras’s monopoly over the hydrocarbon sector. Oil prices were low then. However, after the 2008 financial crisis, oil prices hovered around $110 per barrel between 2011 and 2014, thereby supporting the government’s view of pre-salt as a massive bonanza.

The relaunching of the bid rounds in 2013, however, shortly faced a double whammy. After the summer of 2014, oil prices more than halved, and meanwhile, a series of scandals hit Brazil’s national champion, Petrobras, and several high-ranking officials. The moratorium on licensing rounds and the developments that followed affected the oil sector and contributed to the decline in Brazil’s proven oil reserves.

To turn the page on that dark phase, in 2016, the government embarked on a new oil and gas strategy that was described as the “greatest transformation” of the sector since the foundation of Petrobras in 1953. The plan involved an aggressive allocation of oil and gas blocks with improved terms in all areas to boost exploration and production. An average of nine rounds were scheduled between 2017 and 2019. Encouraging competition was at the heart of the reforms, especially since it was the liberalization of the industry that led to the rapid ramp-up in production during the previous decade.

The government amended the 2010 pre-salt law to allow foreign companies to become operators in the region. Petrobras still has the right of first refusal, although if it wished to participate, its participation in a consortium could be less than 30 percent.

Facts & figures

Pre-salt auctions

The two most anticipated auctions, scheduled for 6 and 7 November 2019, related to pre-salt blocks: the Transfer of Rights (TOR) and the 6th pre-salt round. In both rounds, the PSA model would apply; the winners would be those offering the highest share of production to the government, though the minimum share was preset.

Under the PSA model, winners also pay a predetermined signature bonus upon signing of the deal, in addition to a long list of fees and taxes to be paid throughout the life cycle of the project. From a government’s perspective, the signature bonus is a popular mechanism for generating upfront cash, long before any oil production starts. Once paid, the bonus will not have any further impact on project economics, though it has a material impact on the life cycle return to the investor.

Overemphasis on the collection of signature bonus revenues can have drawbacks.

Overemphasis on the collection of signature bonus revenues can have drawbacks. Money spent on bonuses is money not spent on exploration. In the long run, successful exploration and ensuing developments are likely to deliver much higher value for the state than signature bonuses. Still, it takes a long-sighted government to acknowledge that.

The 6th pre-salt auction offered four blocks (Aram, Bumerangue, Cruzeiro do Sul, Sudoeste de Sagitario and Norte de Brava). Under this round, Petrobras exercised its preemptive right to operate the two largest fields on offer, as stipulated in the 2016 legislative reform.

The TOR round offered four blocks (Atapu, Sepia, Buzios and Itapu), which are thought to total around 6 billion barrels of oil equivalent (BOE). However, this was not a straightforward auction. Following the 2010 legislative changes, the government guaranteed Petrobras 5 billion BOE in production. The firm, though, discovered additional volumes in these areas, and it was that surplus that was going to be awarded to the private sector through the bid-round. The winners would have to compensate the state-owned company for the investments it had carried out in that respect. They also had to enter into joint participation agreements with Petrobras since the fields on offer are either under development or in the production phase – a true regulatory quagmire.

Expectations

Around 31 firms, including major companies such as Shell, ExxonMobil and Equinor, expressed interest in participating in the rounds. However, the number of companies that express interest is typically much smaller than the number of companies that end up bidding.

Nevertheless, many expected aggressive bidding and intensive competition. Marcio Felix, Secretary of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels of the Ministry of Mines and Energy, said in a speech delivered ahead of the auctions that “the bidding rounds to be held in Brazil in the second semester shall be a breakthrough in the world’s oil industry. The giant oil volumes of those fields will attract all the participation of major oil companies in those rounds. For Brazil, all that only means one thing: job-generation and prosperity for our people. This is a unique opportunity that shall not be wasted.”

Facts & figures

Similarly, Energy Minister Bento Albuquerque described the TOR as “the world’s largest oil and gas tender,” referring to the potential of signature revenues that would be generated from a round where signature bonuses alone would amount to around 106 billion reais ($25.8 billion). The government would also generate more than $152 billion over the next 35 years.

The outcome of the rounds, however, shattered those expectations.

Washout

A key ingredient for the success of an auction is competition, which turned out to be limited in the latest two pre-salt rounds. Oil giants withdrew their participation and the only bids received were from one consortium led by Petrobras, with minority equity for Chinese partners, in addition to sole bids made by Petrobras. In brief, there was no competitive bidding.

Several factors contributed to these disappointing results. The presence of resources is an important starting point to attract investment, but the Venezuelan experience shows that this by itself is not a guarantee that investors will accept any terms. It is a simple equation: the expected returns should justify the risk while the regulatory and fiscal systems should be internationally competitive.

Oil companies have increasingly become more disciplined and selective.

Since the oil price entered a lower phase in 2014 and stubbornly remained there despite the efforts of OPEC and its non-OPEC allies, oil companies have increasingly become more disciplined and selective at a time when more opportunities have become available.

The Brazilian regulatory and fiscal regimes have failed to adjust to this new reality and offset the attractiveness of pre-salt fields to international capital. Authorities are aware of this shortcoming. “It is an awful system,” Economy Minister Paulo Guedes was quoted saying, referring to the complexity of the rules in place. Energy Minister Albuquerque stated that the government learned a lesson and would adjust the rules of any future auction accordingly.

Scenarios

The outcome of the pre-salt licensing round could dampen ambitious projections about Brazil’s contribution to global oil supplies. In 2013, the International Energy Agency expected Brazilian production to increase to 4.1 mb/d by 2020, a mark that is clearly going to be missed.

The International Energy Agency also predicted production to reach 6 mb/d in 2035 while the ANP expects a higher figure of 8 to 9 mb/d by 2035. These are major increases.

Brazil has the potential to increase its output by at least twofold, but that would require rewriting its terms for pre-salt first, which is a major operational and financial undertaking. Bringing its regime more in line with the new realities of an increasingly competitive global oil industry would mean, for example, reducing the size of the bonus required and adjusting the special privileges given to Petrobras.