Venezuela: How not to run an oil sector

Venezuela sits on the world’s largest oil reserves, but it is not even one of the top 10 global oil producers. Socialist, resource-nationalist policies implemented by former President Hugo Chavez – and continued by President Nicolas Maduro – are behind the country’s poor performance.

In a nutshell

- Venezuela has a wealth of oil, and was once an industry powerhouse

- Socialist economic policies have crippled the sector

- Only a policy transformation can unleash the industry and revive the economy

Venezuela stands out among oil producing countries for its contradictions. Though it sits on the world’s largest proven oil reserves, it is not even among the top 10 producers. It has more than a century of experience with the oil industry, yet in recent years it has become a textbook example of the oil curse. It was a key player in the establishment of OPEC, but today it has little influence within the organization. Once an industry leader, it now holds many lessons for other governments on how not to run their oil sectors. In a nutshell, Venezuela has become a sad story of how bad policies and shortsighted governments can squander the family silver.

Facts & figures

Venezuela: oil and debt

- Venezuela has produced oil since 1914. Large oil deposits were discovered in 1922, significantly boosting output

- Venezuelan diplomat and politician Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo, was a key figure behind the establishment of OPEC

- OPEC’s founding countries in 1960 included: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela

- Oil revenues account for about 98% of export earnings and nearly half of the government’s income

- In November 2017, Russia agreed to refinance $3.15 billion in bilateral loans and delay almost all payments until after 2023

- China is Venezuela’s biggest creditor, with total loans given to Venezuela accounting for more than half of all the loans from China to Latin America

- The U.S. is the primary destination for Venezuelan crude oil exports (41%), as its refineries are equipped to process the country’s heavy oil

Unfulfilled potential

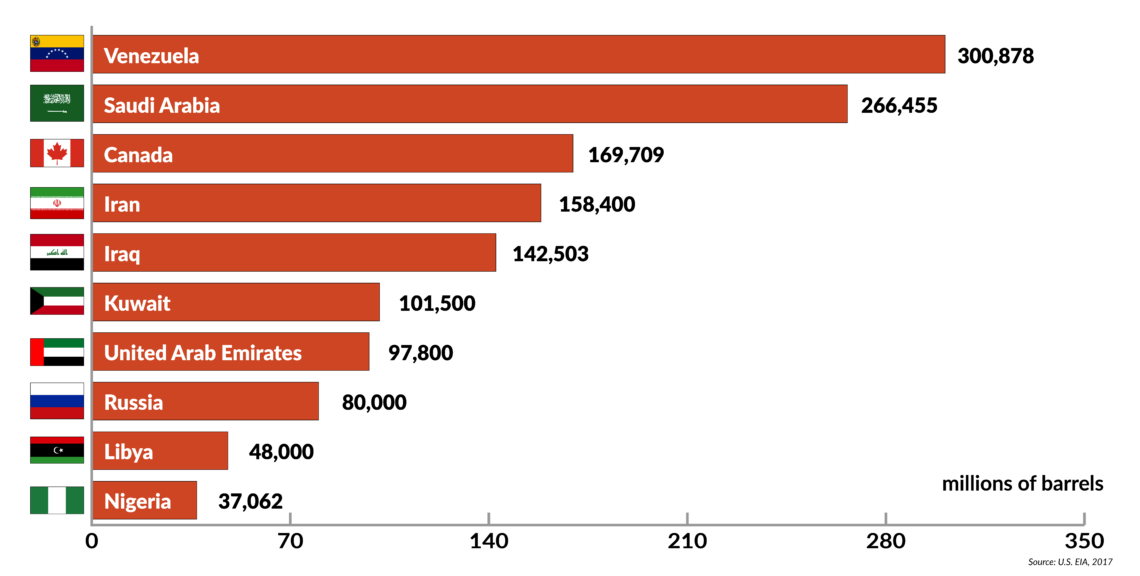

Thanks to the huge deposits of heavy oil in the Orinoco Belt, Venezuela holds the largest proven oil reserves in the world (more than 300 billion barrels or nearly 18 percent of the global total). This massive potential has failed to translate into production, which has fallen in recent years.

In 1998, Venezuela produced more than 3.4 million barrels a day (mb/d), nearly 5 percent of the global total, and ranked as the seventh-largest producer in the world. By 2017, its production had shrunk to 2.1 mb/d and its market share had more than halved. The situation has deteriorated further since then. Production fell to just 1.2 mb/d in September 2018, allowing other producers, including its OPEC partners, to snap up its market share.

Facts & figures

Top 10 countries by proven oil reserves

Production performance

To understand what has led to such a drastic turn in fortune, one must look back several decades. With conventional oil, it takes years, sometimes decades, to convert a discovery into a producing field. Today’s production is the result of investment decisions made many years ago. A combination of factors has contributed to Venezuela’s poor performance in oil production, but government policies have played the most important role.

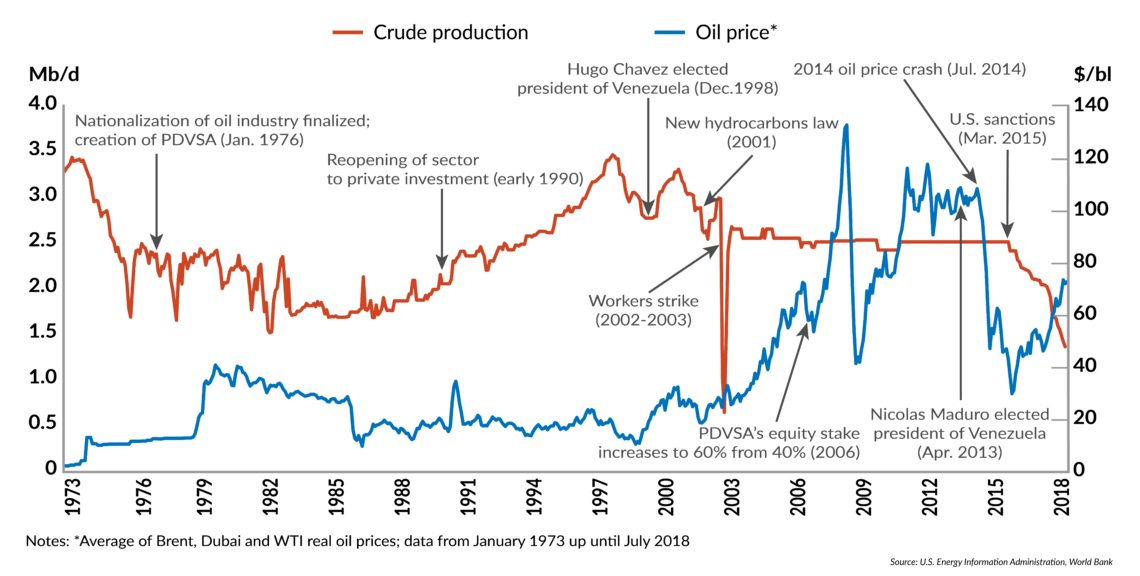

Venezuela’s oil output reached a peak in 1970 at 3.7 mb/d, which then represented around 8 percent of global supplies. However, the trend toward nationalizing oil sectors, which began in the 1960s, culminated in Venezuela in 1976 with the creation of Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA, Petroleum of Venezuela). Production slowed. The situation worsened in the 1980s, when OPEC imposed production cuts on its members following the collapse of oil prices.

Facts & figures

Venezuela crude oil production and prices

PDVSA, though then a respected national oil company, lacked the financial and technical capabilities to develop Venezuela’s deposits of extra-heavy oil in the Orinoco Belt. The government decided to reopen the sector to private investment in the 1990s. Oil production began to recover accordingly, ramping up to 3.4 mb/d in 1998. It has not reached that level since.

A new chapter opened in Venezuela’s history when Hugo Chavez was elected president in December 1998. Since then, the country’s oil sector has fallen into turmoil, irrespective of global prices. The recent decline in production is a manifestation of Chavez’s radical socialist policies, which created a hostile investment climate and stripped PDVSA of its capabilities. These policies remain in place under current President Nicolas Maduro.

Chavismo

Chavez was named one of the most influential leaders in the world by Time in 2005. His controversial policies turned Venezuela upside down and have had an impact far beyond the country’s boundaries.

Originally, Chavez’s fervent nationalist rhetoric greatly appealed to the population; resource nationalism is popular throughout the region. Rising oil prices gave Chavez a helping hand, as they improved the oil-dependent economy’s finances. For the average Venezuelan, Chavez seemed to be fulfilling his promise to restore the economy. But the full effects of his policies were yet to be seen.

Throughout his presidency, Chavez gradually reversed the reopening of the oil sector, frequently implementing drastic changes that created a hostile investment climate. He placed a major burden on PDVSA. Formerly a commercial entity, it began carrying out social programs on behalf of the government, pursuing a political agenda and acting as a cash cow for government extravagance.

Once a commercial entity, PDVSA began pursuing a political agenda and acting as a cash cow for the government.

The government reacted severely when its policies met resistance. For example, after a new hydrocarbons law tightened the state’s grip over the oil sector by strengthening its ownership stakes and increasing taxes on oil companies, PDVSA workers went on strike in December 2002. The strike lasted for a couple of months, during which production and exports were halted. In retaliation, Chavez fired more than 18,000 PDVSA employees – nearly half of the company’s workforce. The result was an irreparable loss of know-how and expertise within the company.

In the following years, Chavez removed various financial incentives offered to international oil investors, raised tax rates and introduced new taxes. He also replaced previous agreements with contracts giving PDVSA a majority equity stake (60 percent) in all oil projects. Oil companies had no other option but to take the new deals or abandon their investments in Venezuela altogether. Most foreign companies reluctantly accepted the new terms. The predominant perception at the time (later proven wrong) was that oil was increasingly scarce. Resource nationalism grew as governments aimed to secure greater control over the supposedly dwindling resource.

In the following years, the impact of Chavez’s erratic policies on production became apparent: despite the high oil prices that prevailed between 2011 and 2014, Venezuela’s oil production was already declining. The collapse in oil prices in the summer of 2014 exposed the cracks in the system. Production has since declined at rates not seen for decades and the trend shows no signs of stopping.

Not just oil

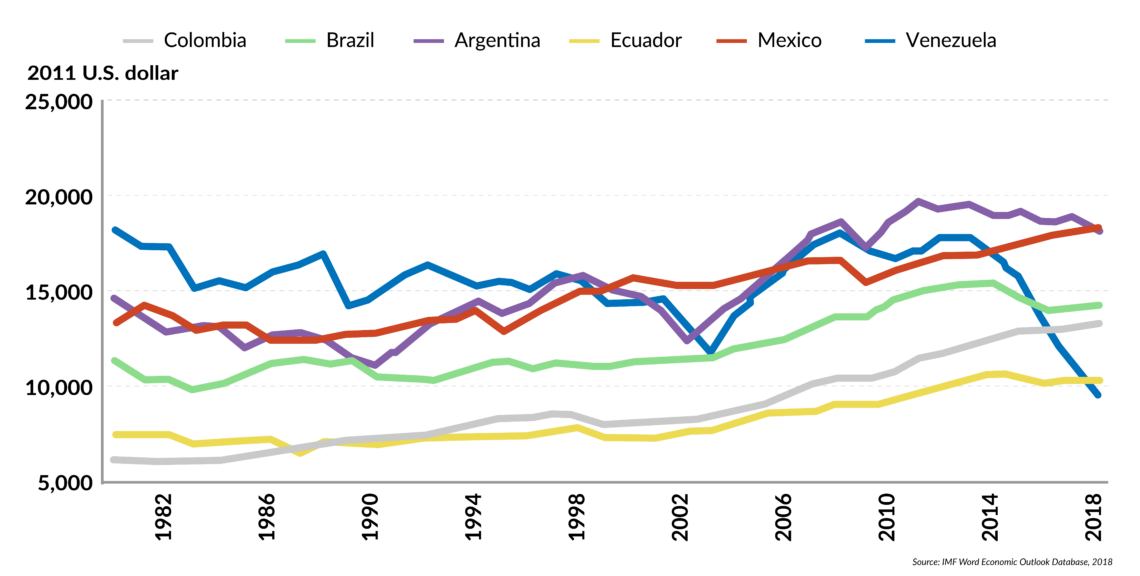

The poor performance of the oil sector has had major repercussions for Venezuela’s economy, with Chavez’s rise to power clearly marking a turning point. Before 1998, Venezuela’s GDP per capita exceeded that of most of its neighbors. Today, it lags behind them. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Venezuela’s public debt more than doubled between 2000 and 2013, from 28 percent to 63 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The government tried to address its growing budget deficit by printing money, but this led to high inflation rates. The IMF projects a surge in inflation to 1 million percent by the end of 2018, making it one of the worst hyperinflationary crises in modern history.

Facts & figures

GDP per capita

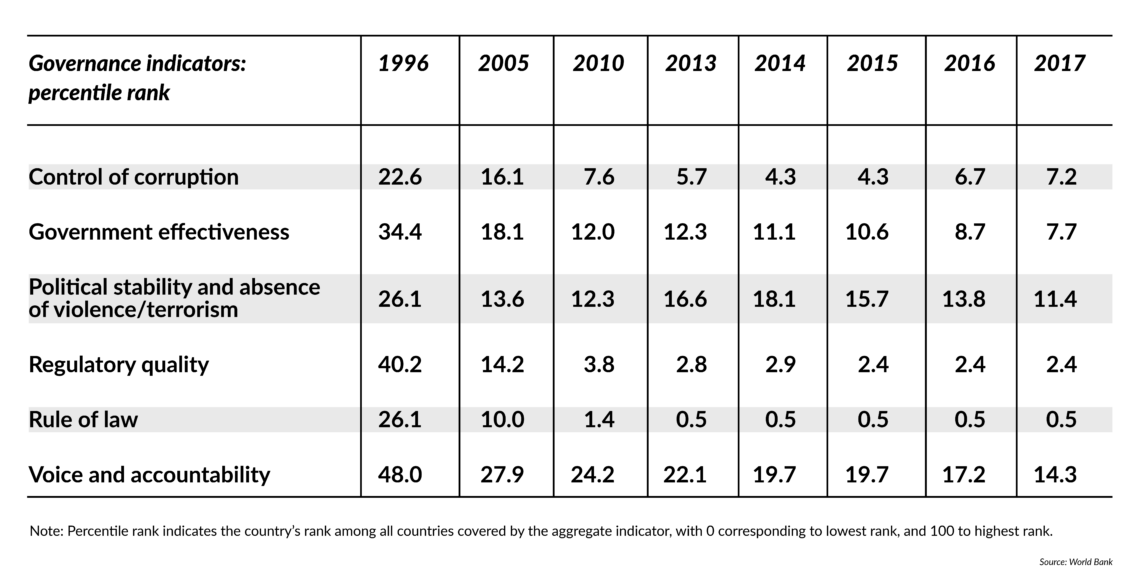

Foreign direct investment has been falling since 1998, in line with Venezuela’s worsening performance on factors important to investors, such as corruption, government effectiveness and credibility, rule of law, accountability and security. In the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, Venezuela ranked 188th (out of 190 countries) overall in 2018. It also scored 169th (out of 180 countries) in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index in 2017.

Facts & figures

Declining attractiveness

In March 2015, the United States imposed sanctions on Venezuela in response to the erosion of human rights and use of violence against protesters in the country. The sanctions have restricted the ability of both the Venezuelan government and PDVSA to raise funds, further worsening the situation. Recent support from Russia and China has had a limited impact, and neither country has any appetite for further risk in Venezuela.

Impact on oil markets

The crisis in Venezuela has had a ripple effect beyond the country’s boundaries. Venezuela’s (involuntary) compliance with the December 2016 OPEC production cuts has reached nearly 800 percent. Its substantial decline in output has boosted the cuts’ effectiveness and put upward pressure on oil prices.

Venezuela’s production fall so exceeded expectations that OPEC members agreed to relax the cuts in June 2018, to ease the pressure that tighter supplies were putting on the market.

Despite sitting on the world’s largest proven oil reserves, Venezuela has fallen behind many of its peers with less potential, including within OPEC. There is no end in sight to its oil production nosedive – it is expected to fall below 1 mb/d by the end of the year.

It will take a lot for Venezuela to restore its market share in an increasingly competitive environment. Its leaders continue to ignore the evidence that a drastic policy reversal is needed. The future of Venezuela’s oil sector, and therefore its economy, will depend on whether common sense prevails among its leaders. For now, that looks like a risky bet.