Cambodia works to balance regional powers

With a reported deal to allow the Chinese military access to a key naval base, Cambodia has gained the attention of those following the Sino-U.S. rivalry. For Phnom Penh, however, its partnership with Beijing is about balancing Vietnam and Thailand.

In a nutshell

- Cambodia may give China access to a key military base

- Ties with Beijing help Phnom Penh balance regional powers

- The U.S., EU and Japan cannot offer the support China has

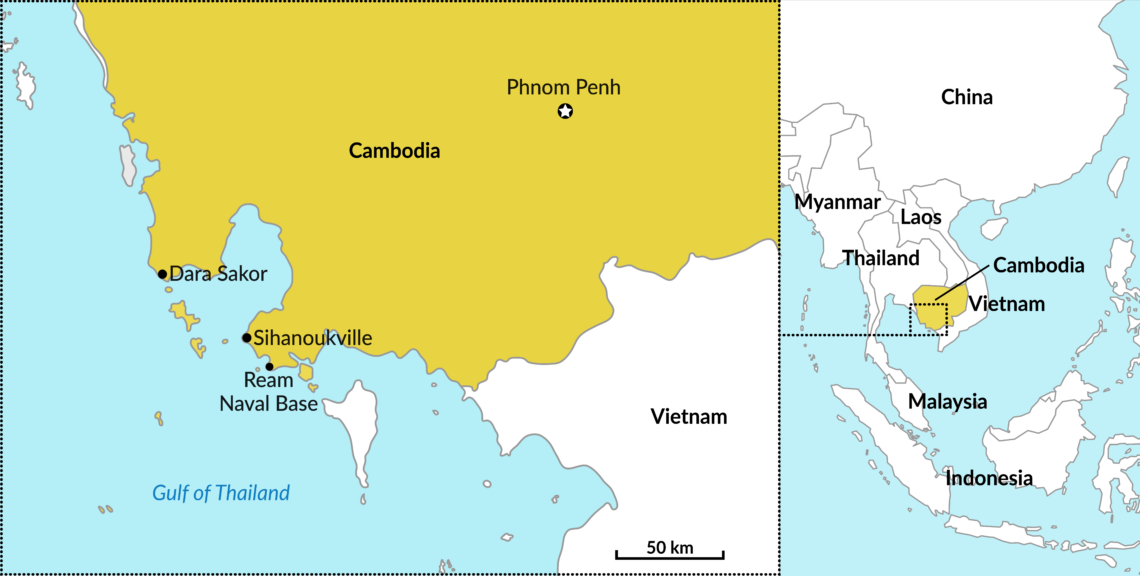

This past summer Cambodia appeared again on geostrategists’ radar screens. The reason for the renewed interest is the reported construction of a Chinese naval base on Cambodia’s coast. The attention is appropriate, but it points to a dynamic that is about far more than the rivalry between the United States and China.

Reports of a new base

On July 22, 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported on a secret agreement between China and Cambodia to expand a naval facility at Ream, on the Gulf of Thailand. According to the deal, the Chinese military would be allowed to have a presence there for 30 years, with negotiated 10-year renewal periods thereafter.

Both Chinese and Cambodian officials have denied the reports. Yet there is plenty of reason to be skeptical of their claims. China also insisted it was not militarizing reclaimed land in the Spratly Islands even as it was carrying out the construction work. The Cambodians, for their part, are expressing their denials by equivocating about what exactly constitutes a “military base.”

Any base will likely not be outright owned or leased by China along the lines of the one it has built in Djibouti, let alone anything like the presence the U.S. once enjoyed in Thailand and the Philippines. That would be such a clear violation of Cambodia’s constitution that even the country’s decades-long autocratic Prime Minister Hun Sen could not get away with it. At home, given the implications for Cambodian sovereignty, he would suffer politically. In the region – which long ago established a norm against the presence of foreign military bases – he would suffer diplomatically. Internationally, he could rightly be accused of violating the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements.

Beijing could be laying the foundation for a military presence in the region larger than any it has had before.

Nevertheless, a major naval facility on the Gulf of Thailand, built by and regularly available to China, would constitute a significant development, not least because of the location’s proximity to another project 40 miles to the northeast. There, at Dara Sakor, a Chinese company is building an enormous investment zone, which will include an international airport capable of handling the largest passenger jets, as well as Chinese bombers and military transports. Together with its South China Sea outposts, Beijing could be laying the foundation for a military presence in the region larger than any it has had before.

China-Cambodia relations

A possible meeting of the minds between Phnom Penh and Beijing on a modest military presence is not surprising. The current rumors about Chinese designs for the Ream Naval Base go back more than 10 years. Moreover, Cambodia is China’s most reliable friend in Southeast Asia.

Over the last decade, Cambodia has been an active proponent of China’s positions in several very high-profile disputes. In 2009, it summarily deported 20 asylum-seeking Uighurs to China, despite its commitment to the 1951 Refugee Convention and in the face of international opprobrium. Most famously, in 2012, it blocked a consensus statement in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) regarding China’s aggressive activities in the South China Sea and precipitated a very similar deadlock again in 2016.

When it comes to Taiwan, Cambodia has been particularly deferential to Chinese interests. In 1997, it shut down the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office, the sort of unofficial presence Taiwan has all over the world, including in 19 other Indo-Pacific countries. It has even prevented Taiwan from opening a trade office and does not permit the display of Taiwan’s national flag. Deportations have been a useful tool for proving loyalty to China. Cambodia has deported Taiwanese fraud suspects to China, as opposed to their home country, despite Taipei’s protests.

Beijing has rewarded Cambodia handsomely for its fealty. China has been the largest source of international investment in Cambodia for many years. Today, it accounts for more foreign investment in Cambodia than all other countries combined. Major projects have included dams, thousands of kilometers of roads, bridges and free trade zones. The once small coastal town of Sihanoukville is now regarded as a near-colony of China, dominated by Chinese investments, immigrants and tourists.

Largely as a result of all this attention from China, Cambodia enjoys the fastest-growing economy in Southeast Asia – despite its extraordinarily bad business environment. When it comes to trade, the European Union and the U.S. are much larger export markets for Cambodia. However, China is Cambodia’s largest trading partner due to the huge volume of imports the latter takes in from the former. Beijing is also Phnom Penh’s principal arms supplier and aid donor.

Regional factors

Mainland Southeast Asia has its own complicated geopolitical environment. In this regard, China is not Cambodia’s most vital concern. Thailand and Vietnam are.

By virtue of its size, wealth and military power, Thailand is mainland Southeast Asia’s superpower. It has a contentious history with Cambodia going back 500 years. The most serious recent conflict stemmed from the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia from 1978 to 1989, which jeopardized Cambodia’s value to Thailand as a buffer state between it and Vietnam.

Today, there are occasional military flare-ups along the border, principally around the ancient Hindu temple of Preah Vihear. In 2003, the Thai embassy in Phnom Penh was sacked by Cambodian rioters incited by false reports that a Thai actress had made disparaging remarks about their country.

Feelings of fear and hatred toward the Vietnamese are intense in Cambodia, sentiments similarly rooted in hundreds of years of history. Vietnam’s 1978 invasion and occupation loom large in Cambodian minds. The overthrow of the murderous Khmer Rouge (KR) regime that year, while initially welcomed, quickly gave way to resentment of Vietnamese control and what was rightly seen as more a matter of conquest than morality.

China was the most important player in the effort to expel Vietnam from Cambodia.

For the entire next decade, Southeast Asia’s predominant international concern was how to thwart these ambitions and expel Vietnam. China was the most important player in this effort. First, in 1979, China invaded Vietnam and maintained troops on Vietnam’s northern border. This kept pressure on Vietnam and prevented it from concentrating more forces in Cambodia. At the same time, China became the principal supporter of the KR resistance to the Vietnam-installed government, which was the most formidable fighting force among several armed opposition groups.

On Vietnam’s side was the Soviet Union. Its rapprochement with China in the late 1980s and its eventual collapse was indispensable to achieving Vietnam’s withdrawal from Cambodia in 1989. Still, it is hard to imagine this outcome without China’s assistance to Cambodia. This is well-recognized in Cambodia – and in Thailand, which was also deeply invested in the outcome of the war and had for this reason served as a conduit for Chinese support to the KR.

Cambodia’s alignments

Prime Minister Hun Sen is a former KR cadre commander. After defecting to Vietnam, he returned to Cambodia with the 1978 invasion and quickly rose through the ranks of the Vietnam-installed regime. He is still seen by many Cambodians as a Vietnamese stooge, despite the close relationship he has cultivated with China since the mid-1990s.

Like Hun Sen’s biography, Cambodia’s alignments are complicated. Its interest lies principally in balancing Vietnam. If it moves too close to Hanoi, it risks alienating Thailand and setting public opinion against the government. If it moves too close to Bangkok, it faces similar risks with Vietnam. This makes China a more palatable partner for Cambodia than either of the other two. And while the expanding Cambodia-China relationship may worry Vietnam, there is little Hanoi can do about it. Thailand, which has a more amicable relationship with China, is less concerned about the ties between Beijing and Phnom Penh.

America’s moral qualms about engagement with Hun Sen make it an unreliable partner.

Meanwhile, other relationships that could balance Vietnam are not suitable alternatives. The U.S., EU, and Japan are all important economic partners for Cambodia. The U.S., however, is the only full-range power among them. Yet, from the Cambodian regime’s perspective, America’s moral qualms about engagement with Hun Sen make it unreliable. The distrust on both sides contributes to a limited official relationship.

China has never had such reservations. It supported the KR government from 1975 to 1979 and supported it in exile. Ultimately it changed course and supported the regime Vietnam installed. The U.S. could not bring itself to do any of this.

China’s perspective

China’s perspective concerns its own geopolitics. A strong presence in Cambodia gives it advantages with respect to Vietnam. This is important because it shares a river (the Mekong) as well as both a land border and a maritime border with Vietnam, the latter of which is hotly contested.

China’s relationship with Cambodia serves its broader interests as well. Cambodia gives it access to ASEAN processes, often transmitting Chinese positions undiluted into the regional body’s private councils. If China gains military access to the naval base at Ream as reported, it will be better positioned to protect the sea lanes that are crucial to its trade. The security of China’s commerce, so vulnerable to the U.S. Navy in times of conflict, is a major preoccupation of the Chinese. Cambodia also offers them a market for exports and investment.

None of this conflicts with Cambodian interests. Cambodia and China share a broad desire to limit Vietnam’s reach. The Cambodian government has little concern for freedom of navigation or territorial conflict in the South China Sea. It does not have the long diplomatic cultural connection to ASEAN and respect for it that the older members, like Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore have. It would also be perfectly comfortable with China becoming the predominant power in the region, an outcome the U.S. wants to prevent.

Since its independence in 1953, Cambodia’s foreign policies have often confused those who have viewed the country through the lens of great power competition rather than from the narrower perspective of the Cambodian state. Cambodia, like every other nation in Southeast Asia, is just trying to preserve its autonomy. If doing so means powers like China can use Cambodia to their own ends, then from the Cambodian government’s perspective, so be it.