Chile’s year of change

Chile is entering a new, unpredictable era in politics. Dissatisfied with the status quo, its voters have left the traditional parties in droves and are supporting new, independent candidates. Such independents have been tasked with writing the country’s new constitution.

In a nutshell

- Chileans are rejecting the political and economic status quo

- Independents dominate its Constitutional Convention

- The presidential race has no clear front-runner

Chile has a long-established political and economic model, but its discontented citizens are demanding a deep transformation of the state that goes much further than simply replacing the increasingly debilitated government of President Sebastian Pinera.

If the results from the first half of the year are any indication, many of the country’s political and economic contours are likely to change. Voters roundly rejected the traditional right-wing parties in the country’s Constitutional Convention election, as well as in regional and municipal elections, throwing their support behind the political left or independent and populist alternatives. A surge in Covid-19 infections and renewed lockdowns in the capital of Santiago have further weakened President Pinera. It appears that conditions are ripe for the return of the left in presidential elections in late 2021.

New constitution, new president

Politically, this is an unusually busy year for Chile. On top of casting their ballots in regularly scheduled elections, voters selected individuals to write the country’s new constitution.

A so-called “mega election,” the most consequential in Chile’s recent democratic history, was held on May 15 and 16, 2021, to elect 155 members of the country’s Constitutional Convention. The vote took place at the same time as the first election for regional governors and the selection of other local authorities. Runoff elections for 13 of 16 governors took place on June 13. Select coalitions held primary elections on July 18 for presidential and legislative candidates, and the country’s presidential, legislative, and regional elections will take place on November 21. A presidential runoff, which seems likely, would occur on December 19.

Voters have opted for independent candidates and new political parties.

The outcomes will shape the future of Chile’s politics. Since the transition to democracy in 1989, center-right and center-left coalitions have dominated politics. However, both have lost ground in recent years as mass partisanship has declined and voters have increasingly opted for independent candidates and new political parties. Nowhere were these trends clearer than in the election for the country’s Constitutional Convention.

Alternative politics

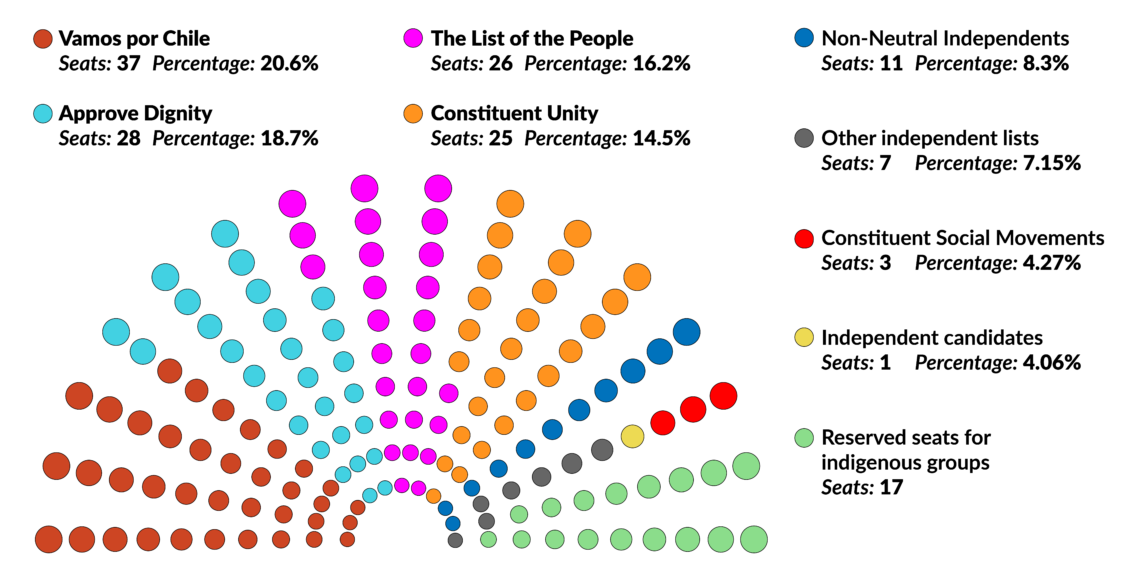

In a blow to the traditional coalitions that have governed since re-democratization, voters overwhelmingly opted for independent candidates and alternative coalitions. Although the governing center-right Chile Vamos received the largest number of votes, it won only 37 seats, representing less than a third of the delegates. Meanwhile, Approve Dignity – a left-wing alliance of the Communist Party, the Broad Front and Chile Digno (Worthy Chile) – placed second, with 28 seats. The List of the People, an antiestablishment coalition of independent candidates, finished third with 26. Constituent Unity, the successor to the Concertacion, which was the main center-left coalition until 2013, finished in fourth place, with 25 seats. Other independents won an additional 22 seats. In short, the lion’s share of delegates elected to the Constitutional Convention were independent candidates organized in new political groupings.

Facts & figures

Chile’s political coalitions

There were four main coalitions in the May elections:

- Vamos por Chile, a center-right grouping of the Independent Democrat Union (UDI), National Renewal (RN), Democratic Independent Regionalist Party (PRI), and Political Evolution (Evopoli)

- Constituent Unity, on the center-left and made up of the Christian Democrat Party (PDC), Radical Party (PR), Socialist Party (PS), Party for Democracy (PPD), Progressive Party (PP), and Citizens Party

- Approve Dignity on the far left, comprised of the Equality Party, the Broad Front, and Chile Digno

- The independent List of the People

The delegates therefore represent a bottom-up alternative to the stable, centrist coalitions that have dominated the country’s politics since 1990. This should not be much of a surprise. The possibility of drafting a new constitution arose following the widespread protests that erupted in 2019 against social and economic inequality, and due to dissatisfaction with establishment politicians and political parties. The desire for change went beyond the demonstrators. In a plebiscite in August 2020, 78 percent of Chilean voters supported convening a constitutional convention (opposition largely came from the right).

The results suggest that Chilean politics is headed for a new era of unpredictability, where political parties will play a decreasingly important role in shaping politics – including in November’s presidential election.

Covid-19

Amid the busy electoral calendar and the seating of the Constitutional Convention, Chile is also confronting another surge in Covid-19 infections, despite having one of the most successful vaccine rollouts in the world.

Although more than 12.4 million of the country’s 15.2 million adult population have received at least one dose of the vaccine (and 10.2 million two doses), in late May the country began experiencing a swell in infections, hospitalizations and deaths. In the capital region, hospitals filled up. Some causes include loosened coronavirus restrictions in the Southern Hemisphere summer to mitigate the hardship caused by quarantine measures, as well as dependence on the Chinese Coronavac vaccine, which has been shown in trials to be less effective than its counterparts developed in the United States and Europe.

Facts & figures

As a result, on June 10 the Pinera government reimposed lockdown restrictions, including especially stringent ones in the Santiago Metropolitan Region. Then, on June 24, the National Congress of Chile approved the president’s request to extend the state of emergency another 90 days. The announcements mark setbacks for Chile’s economy and efforts to reopen the country, and have led to criticism of the president from across the political spectrum – including from his own coalition. The measures could also exacerbate social discontent.

Ominously, Chilean authorities also recently confirmed the arrival of the more infectious Delta variant of Covid-19, which could pose further challenges to the country’s recovery.

Scenarios

The Constitutional Convention held its inaugural session on July 4, electing as its president Elisa Loncon, a Mapuche linguist and rights activist. Her election reflects the body’s progressive majority and its attempt to break from the country’s political establishment. The body now has nine months to produce a new constitutional text that will then be subjected to a national referendum sometime in 2022.

The Constitutional Convention election results represent broad support for the drafting of a radically different constitution. It is nearly certain that the document will be more progressive. Delegates will push to decentralize power, redistribute wealth, protect the environment and give the state more power to intervene in Chile’s free-market economy (set in place under dictator Augusto Pinochet). It is this economic structure that the political establishment has largely endorsed, and which protesters have so loudly opposed. Only the Vamos por Chile coalition – which has 37 seats, less than the one-third needed to veto articles in the new text – will oppose changes to the free-market system.

Ultimately, though, the text may not be as radical as some hope. The fragmentation of the body and the number of political independents advocating a variety of causes mean that it will be difficult for any single group to impose its political will. The high degree of political pluralism in the convention means that reaching consensus over a new constitutional text will be difficult, and delegates do not appear to agree on much.

Chile’s constitution will almost certainly include protections that are a part of the constitutional texts in Venezuela (drafted in 1999), Ecuador (2008) and Bolivia (2009). Among these provisions is recognition of the countries’ indigenous peoples, something all but assured with the election of Dr. Loncon as convention president. However, unlike the hyper presidential texts in those other places, Chile’s document is likely to strike more of a balance between legislative and presidential powers

One risk will be the legitimacy of the convention and the text itself. In 2019, more than a million protesters took to the streets to demand a new constitution, but low voter turnout rates of 43 percent in the convention elections and the historically low participation rate of 19.6 percent in the gubernatorial runoff have fueled concerns about voter apathy. If the drafters fail to include many of the progressive elements demanded by social activists, people may seek to force political change by taking to the streets once again.

The convention’s work is likely to cast a shadow over existing political and social tensions, which the outgoing administration will manage until the end of its term in March 2022. Among other things, the process could become a source of tension between conservative groups and more radical ones, as the latter seek to incorporate various historic social causes into the text.

These tensions and debates will also play out in the presidential race, where there is no clear front-runner. For now, the presumptive favorites are: Gabriel Boric, a former student leader who upset Communist Party candidate Daniel Jadue in the leftist Broad Front coalition primary election; Sebastian Sichel, an independent candidate who upset the traditional rightist Independent Democrat Union’s Joaquin Lavin in the right wing coalition’s primary; and current Senate President Yasna Provoste of the center-left Christian Democrat Party, who has yet to be officially nominated. Populist figures like Pamela Jiles could also play an important role.

It is early in the race, but if present trends hold, the presidential election will probably go to a runoff in December. Several independent candidates and other parties that are outside of the primary process will participate, and as the Constitutional Convention election showed, the Chilean electorate no longer exhibits strong partisan ties.

The most likely outcome is a victory from the center-left. The success of the Constituent Unity coalition in June’s regional elections indicates that moderate leftist parties are still well-positioned for November. Mr. Boric, however, is a far more palatable candidate to moderate voters than Mr. Jadue would have been, and could prove to be stiff competition for Ms. Provoste for the center-left and left vote. What is clear is that the right is competing from a position of weakness, and a rightist candidate would likely lose a runoff election against a moderate leftist.

Still, Mr. Sichel has a path to victory through exploiting divisions among the left. While Mr. Boric and Ms. Provoste may be competing to split the votes among their supporters, Mr. Sichel seems poised to carry the conservative vote, about a third of the electorate, and move into the runoff. There, his path to victory would be through garnering the support of disaffected centrists – something he could do as an independent politician who has belonged to parties of both the left and the right.

Lastly, it is plausible that a populist outsider like Ms. Jiles or Jose Antonio Kast slips into the second round, harnesses anti-incumbent and antiestablishment sentiment, and emerges victorious against Mr. Boric, Mr. Sichel, or their ilk. This was the exact formula that led to Pedro Castillo’s recent presidential victory in Peru and is always a possibility in two-round voting systems – especially when the party system is fragmented and mass partisanship is weak, as is now the case in Chile.

Chile’s social situation makes clear that all candidates, including those on the right, would face pressure to grow the role of the state, regardless of the contents of the new constitution.