Chile’s Pinera struggles to make headway

Chile’s President Sebastian Pinera is facing resistance to his reforms from a hostile congress. His clumsy handling of several domestic crises has not helped his government gain traction. The economy is doing well, though, fueled by copper exports.

In a nutshell

- Pinera’s reforms are being blocked by a hostile legislature

- Mismanagement of crises has distracted from his agenda

- The economy is growing, but is highly dependent on copper

- Diversification into lithium requires streamlining regulations

Chile finds itself facing new variations on old challenges. Economically, the country’s main concern always has been copper markets, which have been increasingly rattled by the trade dispute between the United States and China. Recent electoral reforms have made it more challenging to build coalitions, threatening to bring the government to a standstill.

President Sebastian Pinera, two years into his four-year term, is struggling to pass crucial pension and education reforms in the face of congressional resistance. He also would like to make the tax system more business-friendly. The opposition, however, shows little sympathy for this plan. Two factors complicate the president’s situation. First, his center-right party, National Renewal (Renovacion Nacional, or RN), does not hold a majority of seats in congress. Second, electoral reforms that went into effect in 2016 have favored the growth of smaller parties, which do not need to marshal a majority of votes in a particular district to gain representation. This has reduced incentives for cooperation.

Since Chile will still elect a president in a nationwide runoff vote, it is increasingly unlikely that a president will have a simple majority in congress. More complex and less durable forms of coalition-building will likely become the norm.

President Pinera has shown himself to be maladroit in legislative consensus building.

Even considering the structural challenges he faces, President Pinera has shown himself to be maladroit in legislative consensus-building. On June 1, he presented his annual “Public Account” speech on the state of the nation. It was remarkable for its litany of proposals, but offered few suggestions as to how they would pass an opposition-led congress.

One stumbling block, emblematic of Mr. Pinera’s political ham-fistedness, concerned pension reform. As a compromise measure and a gesture of outreach to the centrist Christian Democrats, a major opposition party, President Pinera’s government had indicated that it would create a state-managed fund to invest new social security contributions, rather than continuing to rely on deeply unpopular private funds. In his speech he seemed to renege on this promise, leaving the Christian Democrats bewildered and angry, and seemingly dashing hopes of compromise.

Domestic difficulties

Meanwhile, the president’s political capital has been sapped by several domestic crises to which his response has been widely deemed insufficient. The first were forest fires that raged throughout the austral summer – the government’s failure to get them under control has become symbolic of broader frustrations with state inefficacy. This summer alone, nearly 100,000 hectares of land were consumed by fires that ranged from Chile’s most remote southern regions to Santiago’s most famous public park. In addition to threatening lives and homes, such conflagrations threaten Chile’s industrial forest plantations, the heart of a $7 billion export industry, making up about 10 percent of total Chilean exports. This year’s fires came in the wake of what then-President Michelle Bachelet (2014-2018) referred to as the “greatest forest disaster in our history,” in which 700,000 hectares of land burned.

Besides the fires, undoubtedly the most devastating blow to the Pinera presidency came late last year, when state police forces killed Camilo Catrillanca, a young indigenous leader. In a case that has echoed the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S., initial claims by police about the circumstances of Catrillanca’s death were ultimately shown to be an extensive chain of lies. The indigenous leader, it turned out, was shot in the back while driving a tractor home from work. He was hardly the violent terrorist that police described.

As a result, calls grew to disband the Jungle Command, President Pinera’s prized elite police force that was supposed to crack down on domestic terrorism. The Catrillanca case stretched on for months as one police cover-up after another was discovered. The president ultimately woke up to the profundity of the institutional crisis he faced: he announced a program to modernize the police and demanded the resignation of nearly a dozen officials, including the head of the national police force, Hermes Soto. Still, the Catrillanca case revealed the political risks of the tough-on-crime approach at the heart of President Pinera’s political identity.

Criticism of Venezuela

Regional geopolitics and the chaos in Venezuela have offered President Pinera a platform to rise above domestic concerns. In January, he flew to Cucuta, Colombia, on the border with Venezuela, to join other regional leaders in supporting Venezuela’s self-declared president, Juan Guaido. Mr. Pinera has been unrelenting in his criticism of the Maduro dictatorship. Several other right-leaning Southern Cone leaders, including Mauricio Macri in Argentina and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, have joined in the criticism – they all forcefully insist that Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro must be deposed. The U.S. and most European nations support their position.

President Pinera’s detractors have accused him of political showmanship in traveling to Cucuta, seeking an unnecessary photo shoot far from Chile in an effort to distract from problems at home. His anti-Maduro stance has energized members of his base, who want to prevent Chile’s domestic socialists from taking power and turning Chile into what they call “the next Venezuela.”

Prosur is best understood as a political ploy.

In a further attempt to isolate Venezuela, President Pinera and other right-leaning South American leaders have created a new trade bloc. Called Prosur, the new grouping replaces the former Unasur, a trading and defense union that included Venezuela but had become inactive after several Latin American nations refused to cooperate with the Maduro regime. Prosur is best understood as a political ploy: it makes no major changes to Unasur, except the addition of a clause that requires all participating nations to uphold democratic principles.

Copper dependence

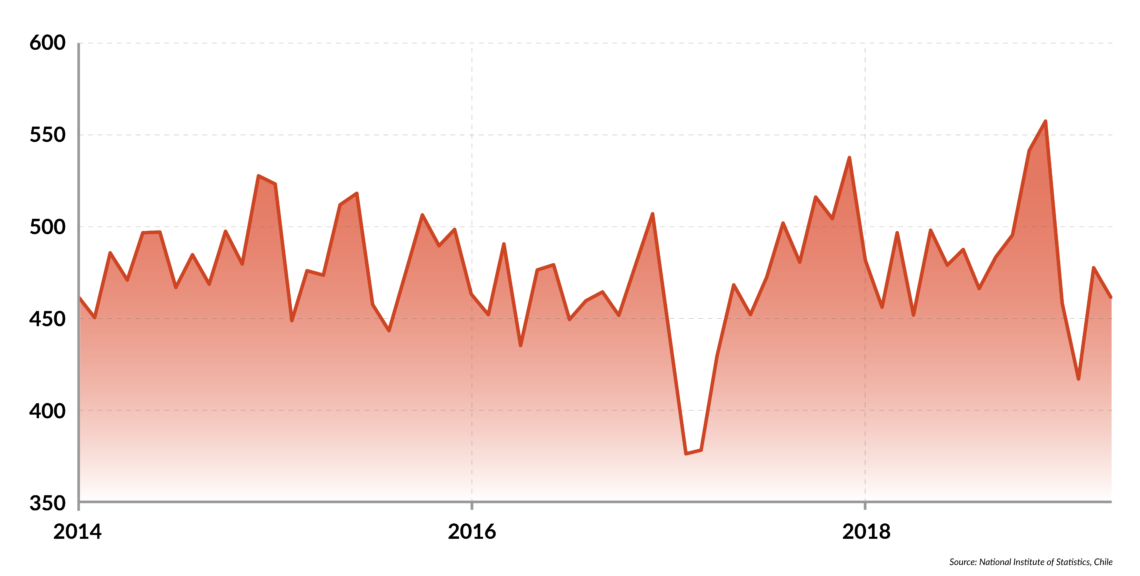

Chile’s economy is humming, but its strength is rooted in the same unpredictable commodities cycles that have determined Chile’s growth for a century. Its gross domestic product (GDP) increased by 4 percent in 2018, considerably higher than the sub-2 percent rate averaged under the previous administration. This is an indisputable victory for President Pinera. But the data behind the growth show that it could be as ephemeral as ever. Production of copper, which still makes up nearly 50 percent of Chile’s exports, surged to record-breaking levels at the close of 2018, driven primarily by output from the state-owned firm, Codelco. However, Chile risks becoming collateral damage in the growing trade war between its two largest trading partners, the United States and China.

Copper prices have suffered because of uncertainty about Chinese demand, and they will continue to fluctuate until global markets can gain more assurance about the U.S.-China trade dispute. Currently, copper is hovering between $2.50 and $3.00/lb, which provides revenue for the Chilean government. While this price is a pittance compared to the heights it reached between 2006 and 2010, it is much better than the low of $1.50 during the 2008-2009 financial crisis or the less than $1.00 it hit before China began its buying spree 20 years ago.

Recently, President Pinera has held prominent meetings with both U.S. and Chinese leaders, who are trying to prevent Chile from falling into the other’s economic orbit. In early April, he met with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who urged Mr. Pinera to be skeptical of the sweeping Chinese Belt and Road Initiative. Repeating language that many U.S. diplomats have invoked, he declared Chinese business practices “nefarious” and “predatory.” These warnings did not seem to impress Chilean leaders. Barely 10 days later, President Pinera flew to Beijing to meet with Chinese investors, telling them: “We want to transform Chile into a business center for Chinese companies, so that you can, from Chile, reach out to all of Latin America.”

Facts & figures

Cruising on copper

Chile's copper production, 2014-Q1 2019 (thousand metric tons)

Most visibly, he has thrown his support behind a $2.4 billion Chinese proposal to construct a high-speed rail line between Santiago and Valparaiso, the seat of the Chilean Congress. If the Chinese proposal succeeds, it would surely provide an opening for more Chinese-sponsored infrastructure initiatives in Chile and throughout the rest of Latin America.

The irony of Mr. Pinera’s simultaneous denunciation of Venezuela’s autocracy and embrace of Chinese investment was not lost on local political commentators and members of the opposition. During his trip to China, President Pinera deferentially declared that “every country has a right to the political system of its choosing,” a principle at odds with the ostensible reason for creating Prosur. But kowtowing to China is far more important to Mr. Pinera than maintaining warm trade relations with his own neighbors. Over half of Chilean exports go to Asia, while less than 15 percent go to other Latin American nations.

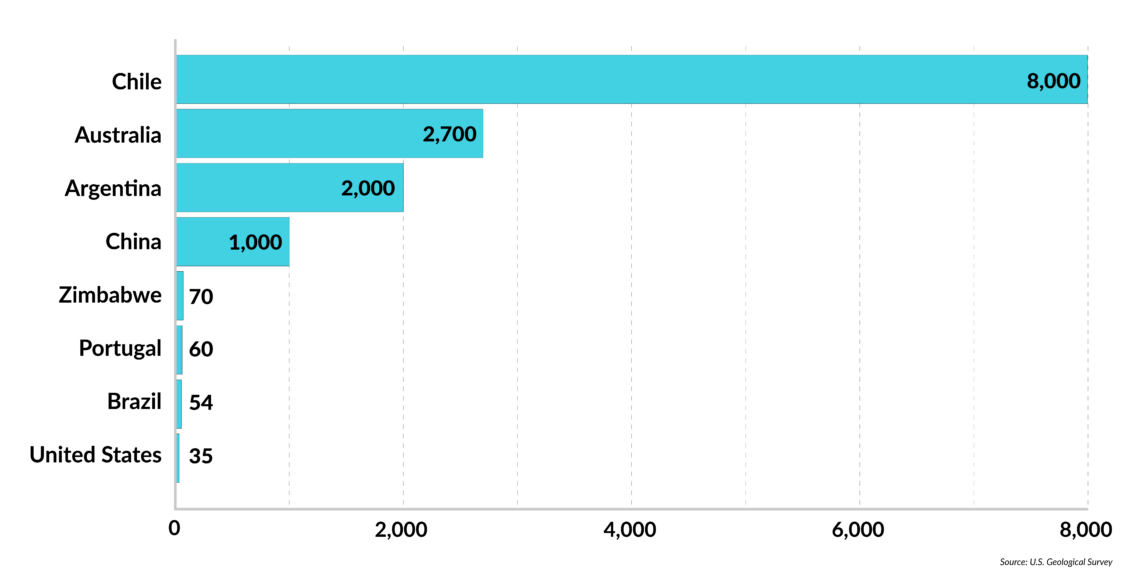

Lithium future

One key variable in Chile’s economic future over the longer term will be lithium. No mineral in the world is expected to be more important during the coming century, given its importance in the production of batteries, especially those found in electric cars. Chile has the largest reserves of lithium in the world, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. How they are managed, and what happens with the lithium that is extracted, will likely determine much of Chile’s economic story over the next several decades.

Currently, only two companies, both of them partly state-owned, exploit Chile’s lithium. In 2017 Australia outpaced Chile to become the largest exporter of the mineral. Indeed, Chilean output of lithium has largely stagnated over the past five years, and its share of the global market has fallen from 36 percent to 20 percent. The sluggishness is largely driven by regulatory challenges, including a complex and vague application process for obtaining lithium mining permits, as well as still-undetermined taxation rates on lithium mining profits.

Facts & figures

Lithium king

Countries with the largest lithium reserves worldwide, 2018 (thousand metric tons)

President Pinera’s pro-market government may move to remedy these regulatory hindrances. Currently, Chile treats lithium as a “strategic” mineral under a law that dates back to the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet and was designed with nuclear fission in mind. The Pinera government could easily change this law and eliminate the byzantine regulatory structure to encourage more private companies to enter the lithium market. Doing so would almost certainly lead to an immediate increase in private investment in lithium mining, though actual increases in production would lag many years behind.

Similar ambiguity exists as to how the government will set taxes on lithium. As it stands, the Ministry of Mining has announced that taxes will be set on a “case by case” basis, which is not a recipe for stimulating growth in the industry.

A final variable is the incentive structure that the Chilean government could apply to make sure that value is added to the lithium product prior to export. There is discussion of fostering battery production within Chile, and Chinese investors have pledged nearly a billion dollars toward factories in the country, in exchange for access to the raw lithium that Chile is producing. After all, refining rare earths is what gives China its geopolitical leverage over the international market. All of this is taking place while rare earths mining in neighboring Argentina and Bolivia is increasing dramatically.

Scenarios

The most probable scenario is that President Pinera will figure out a way to win the votes necessary to pass pension reform legislation. In the short term, that success, together with relative stability in the price of copper, will give the president the momentum he needs to proceed with some of his reforms even without enthusiastic support from the legislature. That, in turn, will stimulate local investment, and enthusiasm for joint ventures with Chinese firms will remain strong. This will create a positive feedback loop, as consumers gain confidence and keep spending.

In such a scenario, President Pinera may manage to create short-term deals with factions of the opposition parties to pass more of his agenda. It is also possible that the government will use executive actions to make regulation of lithium mining more flexible and taxation more transparent, although it may be too optimistic to expect the government to encourage lithium ore refining. Most likely is that lithium taxes will resemble those that already exist on copper, wherein the state receives royalties of between 5 percent and 14 percent on all copper sales, in addition to all profits from the state-owned producer Codelco. The key to progress is to eliminate existing ambiguity surrounding lithium.

A less likely scenario over the next six months is that the trade tussle between Beijing and Washington will lead China to reduce its copper purchases, driving the price below $2.50/lb. In that case, President Pinera’s budget will be squeezed and he will have less to offer potential partners in any legislative deals. In such a scenario, national investors will become squeamish and domestic consumption will lag.

That turn of events would give the opposition new hope and deprive the government of whatever initiative it might have. With copper prices falling, Mr. Pinera would face powerful incentives to immediately place heavier taxes on lithium. Though this would provide short-term budget relief, it would come at the risk of stifling export output in a sector that might eventually rival copper in its importance to Chile’s economy.