Scenarios for Afghanistan’s critical raw materials

Beijing has long had its eye on Afghanistan’s wealth of resources. With the global demand for critical raw materials on the rise, sole control of the Afghan mining sector would have profound geopolitical consequences – not just for China.

In a nutshell

- Afghanistan is rich in high-demand resources

- Beijing could control the Afghan mining industry

- The EU would become even more dependent on China

Afghanistan, which has some of the oldest known mines in the world, has long been famous for its mineral resources. Today, its reserves of gold, silver, platinum, iron ore, copper, lithium and other minerals are of increasing global interest. But exploitation in an unstable, war-torn country has so far proven nearly impossible.

Now that the Taliban have seized power, China could tap into this wealth. Having already invested in Afghanistan’s mining sector during the last decade, the Chinese could come to control Afghanistan’s critical raw materials (CRMs) if the security situation allows it. This would further strengthen Beijing’s strategic control of global CRM supply chains, making the EU even more dependent on China to secure raw materials.

Facts & figures

Afghanistan’s metals and minerals can be transported directly to China via land, including through its $60 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the most important economic corridor of the Belt and Road initiative (BRI). For Beijing, this is an opportunity to expand its dominance of the most important CRM supply chains and reduce its dependence on more vulnerable maritime supply routes for imports.

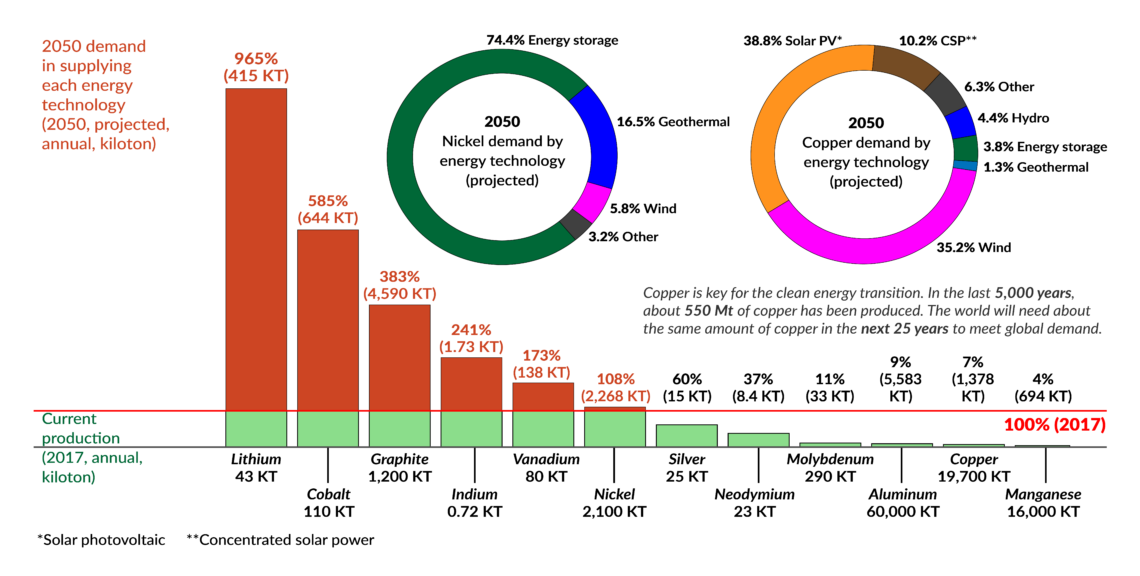

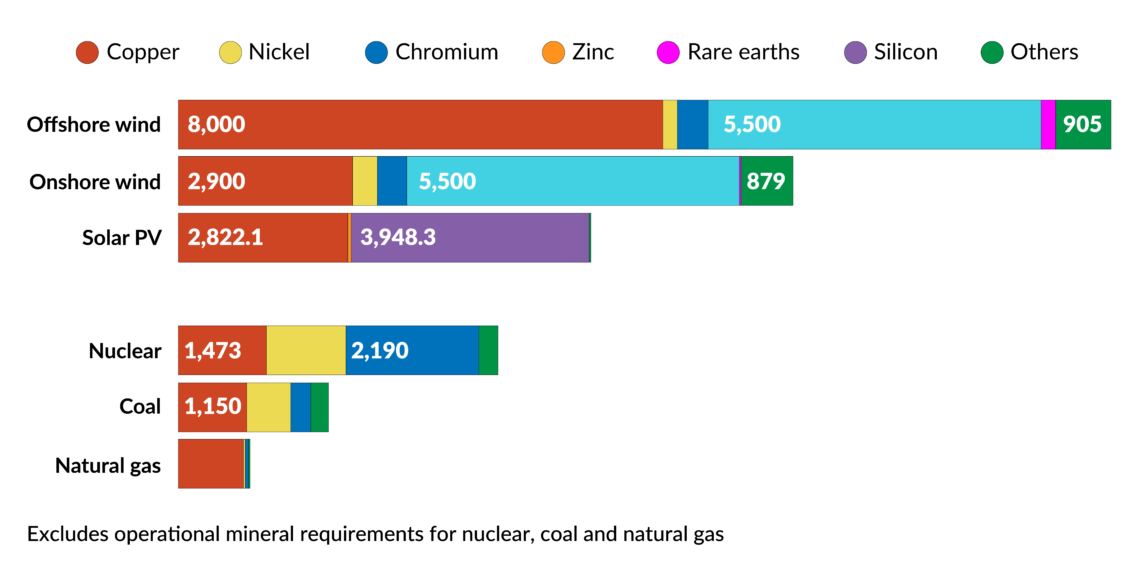

The accelerating green transformation and the rise of new technologies like Industry 4.0 will cause a rapid increase in the need for CRMs. Access to a stable supply will become a crucial geopolitical issue. The European Union’s strategic objectives as laid out in the European Green Deal can only be realized by importing a greater quantity of CRMs from reliable sources. And the Union will have to compete with rising global demand.

Facts & figures

The Fourth Industrial Revolution

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (also known as Industry 4.0) is a term coined in 2016 by Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum. The concept refers to how technologies are converging to change the way we live. It includes nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, 3D printing and human-machine interfaces, among others. Mr. Schwab argued that the Fourth Industrial Revolution “is blurring the lines between the physical, digital and biological spheres.”

According to this line of thinking, the First Industrial Revolution started in the United Kingdom around 1760 with the advent of the steam engine, faster manufacturing processes and factories.

The Second Industrial Revolution occurred between about 1870 and 1914, and resulted from the widespread use of railroad and telegraph networks, and the harnessing of electricity.

The Third Industrial Revolution was also known as the Digital Revolution and occurred in the late 20th century. It was marked by the extensive use of computers.

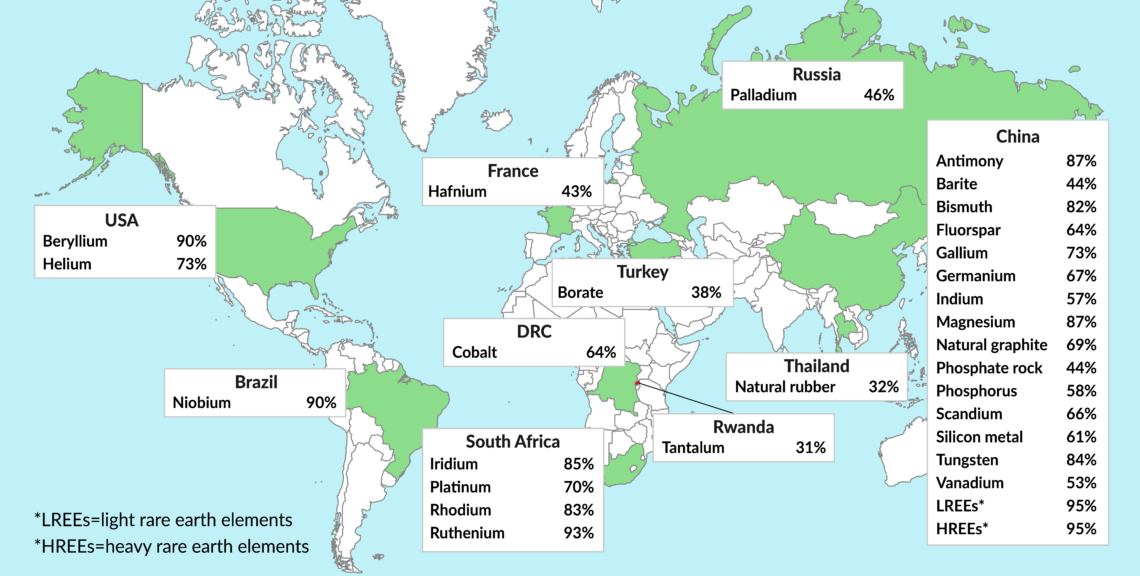

The EU is heavily dependent on China – its most important supplier of CRMs and derived products. Chinese companies control up to 80 percent of the worldwide rare earth elements production, more than 90 percent of its refining processes, some 80 percent of global refined cobalt production, and more than 60 percent of the worldwide lithium-ion manufacturing capacity. China is the only superpower with such a strong position throughout the entire clean technology supply chain.

Against this background, Chinese control of Afghanistan’s mineral-rich mining sector could complicate the EU’s efforts to diversify its CRM imports. But any larger Chinese investments in Afghanistan are still dependent on the country’s future political stability.

Afghanistan’s wealth

To date, Afghanistan and the Taliban have profited from the opium and heroin trade as a major source of hard currency income. Banned from using their foreign reserves in international banks, the Taliban have no other choice than to expand political and economic ties to potential investors, particularly China. In 2010, the United States Geological Survey estimated Afghanistan’s mineral wealth at more than $1 trillion. New value estimates run upward of $3 trillion and may rise further with global demand growth and rocketing prices.

Afghanistan’s mineral industry is still at an exploratory stage.

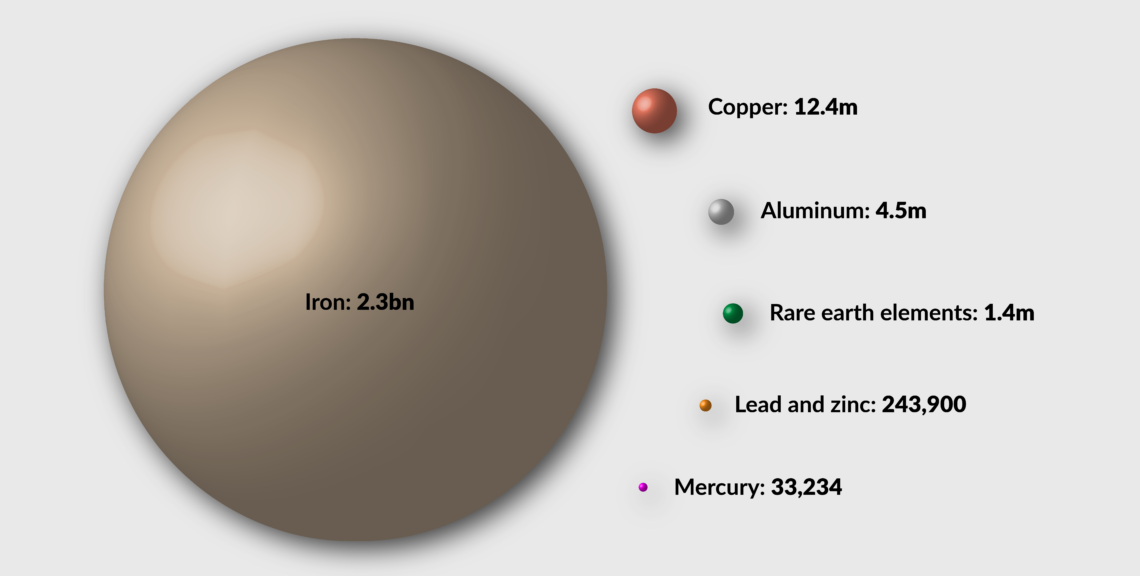

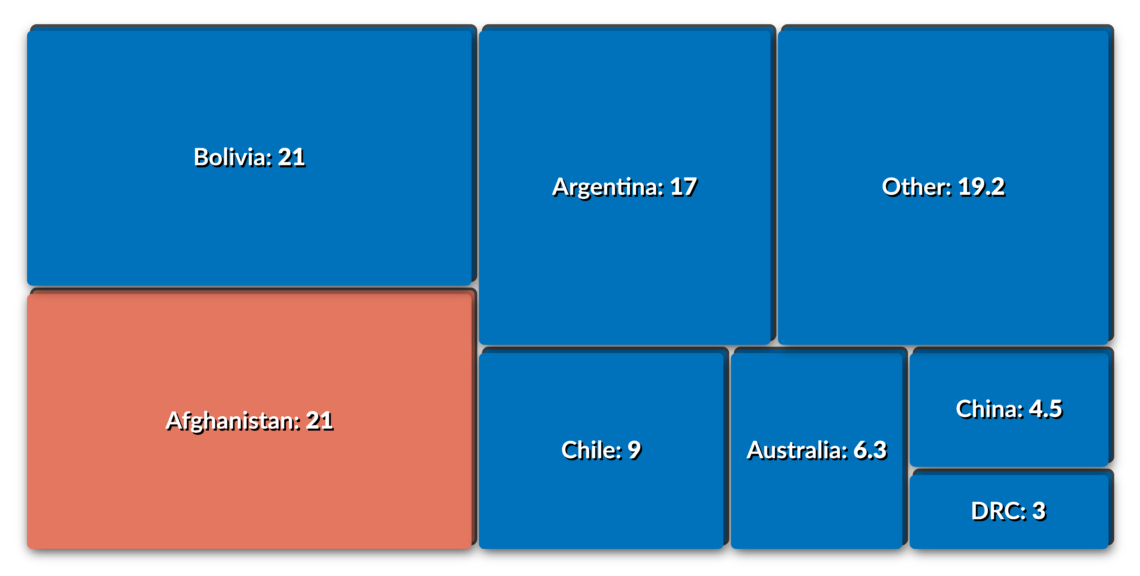

The country’s copper reserves alone are valued at $516 billion. The Mes Aynak deposit, acquired by China in 2008, has been estimated at 11.3 megatons of copper, worth $102 billion at current market prices. The country’s total copper resources may come to nearly 60 megatons. Its 2.2 billion tons of iron ore is worth over $350 billion. Afghanistan’s rare earth resources, valued at $89 billion, may amount to 1.4 megatons, mainly concentrated in the Helmand province. The “Saudi Arabia of lithium” (to quote a 2010 White House memo) could also have a deposit worth $1 trillion – as much as Bolivia, which has the world’s largest reserves.

Facts & figures

In a scenario where the Taliban would not be able to establish a stable government, the security environment would preclude larger Chinese investments. Afghanistan’s membership in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which it joined in 2010, was suspended in 2018. The country ranks 165 out of 180 in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index. Chinese workers and infrastructure in Afghanistan have often been the target of terrorist attacks.

Furthermore, Afghanistan’s mineral industry is still at an exploratory stage, begun by Soviet work in the 1960s and 1970s. The risks for larger Chinese investment and engagement in Afghanistan could therefore outweigh the benefits.

Facts & figures

The EU may also be able to implement its September 2020 Action Plan to acquire a resilient and sustainable CRM supply. In this case, the EU will be able to reduce its dependency on external suppliers by recycling and reusing CRMs and expanding sustainable domestic sourcing and processing. Since 2020, the EU has strived for greater “open strategic autonomy” by relocating critical supply chains (mining as well as refining capacities) to Europe. Cooperation with the U.S. in this field has intensified, especially because Washington has been eager to reduce dependency on China since the Trump years. The Biden administration also aims to build new CRM supply chains for its clean energy agenda.

It remains doubtful whether the Taliban are genuinely interested in exploiting Afghanistan’s mineral wealth. Without Western troops, drug production and trade might thrive anew. And even if their interest is real, it is also uncertain whether they would be able to provide enough security and stability to secure larger Chinese investments in the mining sector. Beijing lost some $300 billion in investments under the last Afghan government, including a $3 billion bid to establish the Mes Aynak copper mine. These projects failed because of numerous disagreements with the Taliban and the previous administration in Kabul.

Facts & figures

In one of the poorest and most fragile states in the world, creating an efficient mining sector, which requires transport infrastructure and sufficient water and energy supplies, will take a long time. It could be many years before the exploration begins and even longer before profits can be earned. Neither security nor corruption can be improved overnight. And even Pakistan’s ability to control the Taliban, on which China has placed its hopes, is limited.

Scenarios

China controls Afghanistan’s raw materials

Dramatic growth in global demand and insufficient investments into new CRM projects could lead to a sharp increase in prices (which have already risen dramatically since last year). This could hamper the decarbonization process necessary to mitigate climate change. If Beijing were to control Afghanistan’s mineral-rich deposits, Europe would become even more dependent on Chinese production and refinement capacities.

In comparison to Western companies and governments, China’s policymakers plan for the much longer term. Securing the supply chains necessary for disruptive technologies and related CRMs is at the top of their agenda. To enhance its economic self-sufficiency, Beijing is willing to pursue ventures that its Western counterparts would deem too politically or financially risky. The industrial strategy “Made in China 2025” states that Chinese companies should use at least 70 percent of domestically sourced components by 2025. The Chinese Communist Party believes strategic control of CRM supply chains will strengthen its geopolitical leverage. In April 2020, President Xi Jinping called for more Chinese products in global supply chains and, simultaneously, for “powerful retaliation and deterrence capabilities against supply cutoffs by foreign parties.”

This scenario would prove highly problematic for Europe, whose CRM import needs are greater than those of the U.S. because it lacks abundant mineral deposits. Only 9 percent of the EU’s overall raw material demand can be supplied by the member states themselves. Europe accounted for only 5 percent of global mining in 2020 and is the only region in the world with a declining mining industry. At present, China provides 98 percent of the EU’s rare earth elements supplies, and around 62 percent of the 30 raw materials it defines as critical. The Union’s demand for lithium is expected to grow 18 times by 2030 and 60 times by 2050. For cobalt, demand could rise fivefold by 2030 and fifteenfold by 2050. Even if the EU creates a circular economy with expanded recycling capacities and domestic European production as well as refinement capacities, it will not be sufficient to guarantee a stable supply for its industries.

The EU’s security of supply policies could also be hampered by a lack of a cohesive supranational power. The European Commission would not be able to compete with China on the global raw material markets because of its stringent environmental regulations and its citizens’ opposition to new mining projects.

As the race for technological independence between Beijing and Washington escalates, geopolitical tensions over critical raw materials will rise. The EU could find itself even more dependent on China and its political goodwill.

Strategic perspectives

The worldwide energy transition has sparked a global race for advanced technologies and the CRMs necessary to build them. The worldwide decarbonization of the global energy sector may create a multi-decade commodity supercycle and increase global geopolitical rivalries.

The Taliban have no choice but to turn to Chinese investments and have already described China as their “main partner.” Beijing will be cautious because of security concerns. Still, it will also want to implement its long-term geopolitical strategy for increasing its global economic relevance by controlling CRM supply chains. Despite the risks, Afghanistan’s proximity to China makes it a natural investment destination compared to more distant BRI locations like Africa and Latin America. If Afghanistan exploits its mineral abundance, it could take center stage in the global competition. While the Taliban might not be able to effectively rule over the entire country, they could control most of its known CRM deposits. These are largely located in eastern provinces close to Pakistan. The CPEC could provide transport infrastructure and allow closer intelligence and security cooperation with China and Pakistan.

Chinese control of Afghanistan’s raw materials would inevitably worsen the EU’s existing dependence on China for decades to come, with all the far-reaching negative geopolitical consequences this implies.