Critical raw materials: Assessing EU vulnerabilities

Securing the supply of critical raw materials that go into advanced technologies has become a political imperative around the world. Rare earth elements present the greatest risk, as China dominates their production. Will the EU manage to limit its geopolitical vulnerabilities?

In a nutshell

- Critical raw materials are increasingly essential to economies

- Europe depends on imports of these materials from China

- The EU is developing plans to secure access to them

As demand for advanced civilian and military technologies grows, it is becoming increasingly crucial for countries to secure a stable supply of the basic materials needed to build them. Dubbed critical raw materials (CRMs), these supplies have become a worldwide concern. For the EU, the issue is even more pressing due to its commitments to decarbonize its economy and its general lack of domestic sources of these materials.

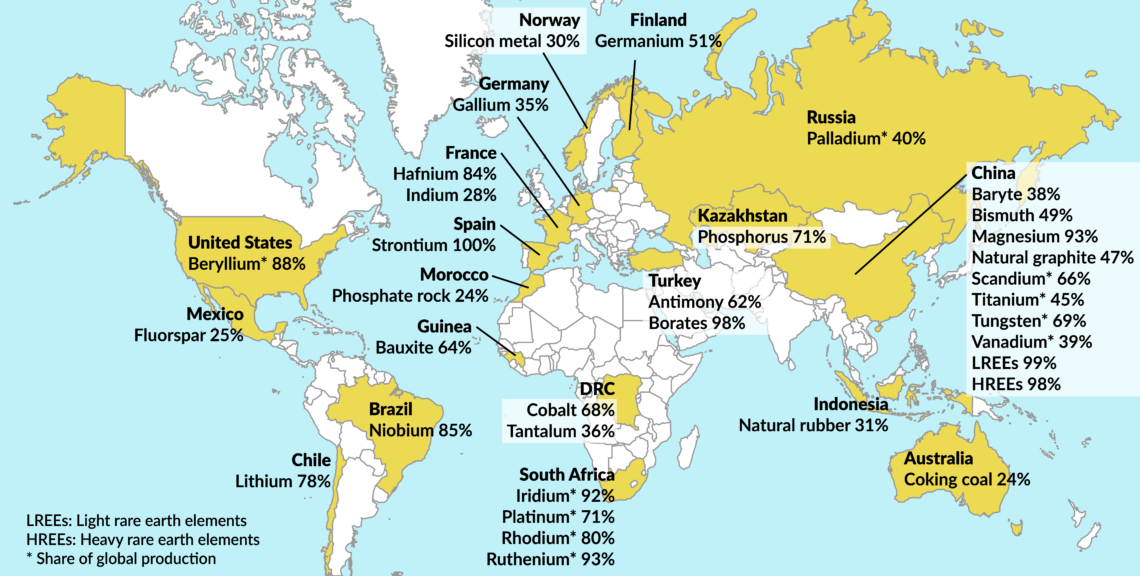

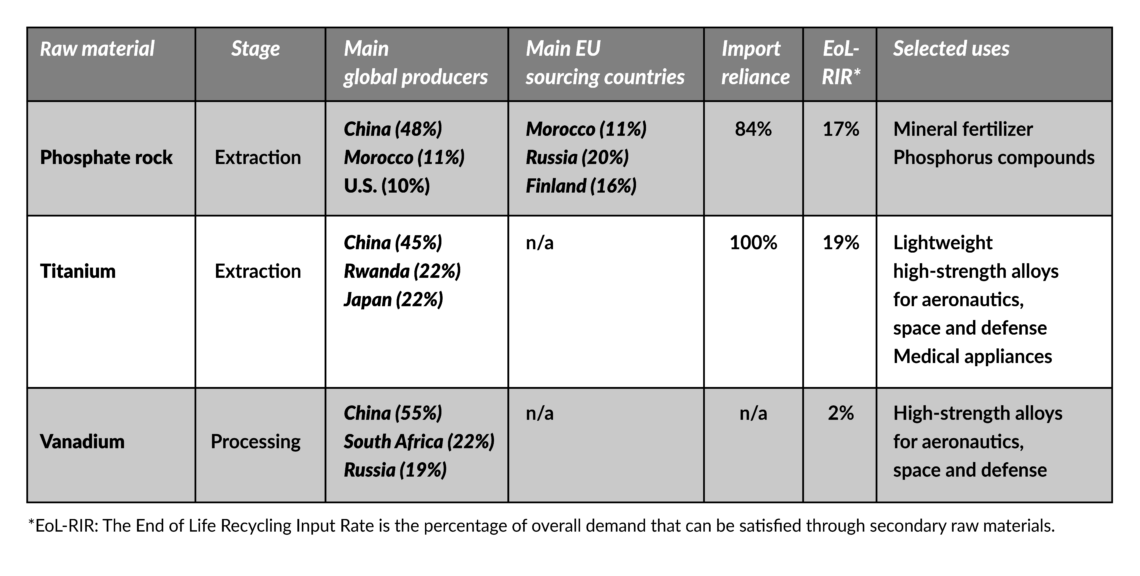

The EU has listed 30 CRMs that it deems crucial for its economy. Among these are materials like lithium, cobalt, phosphorus, magnesium and titanium. The list also includes rare earth elements (both light and heavy) used in nearly all of today’s electronic applications. They are particularly important for the defense and renewable energy industries.

Facts & figures

Rare earth elements

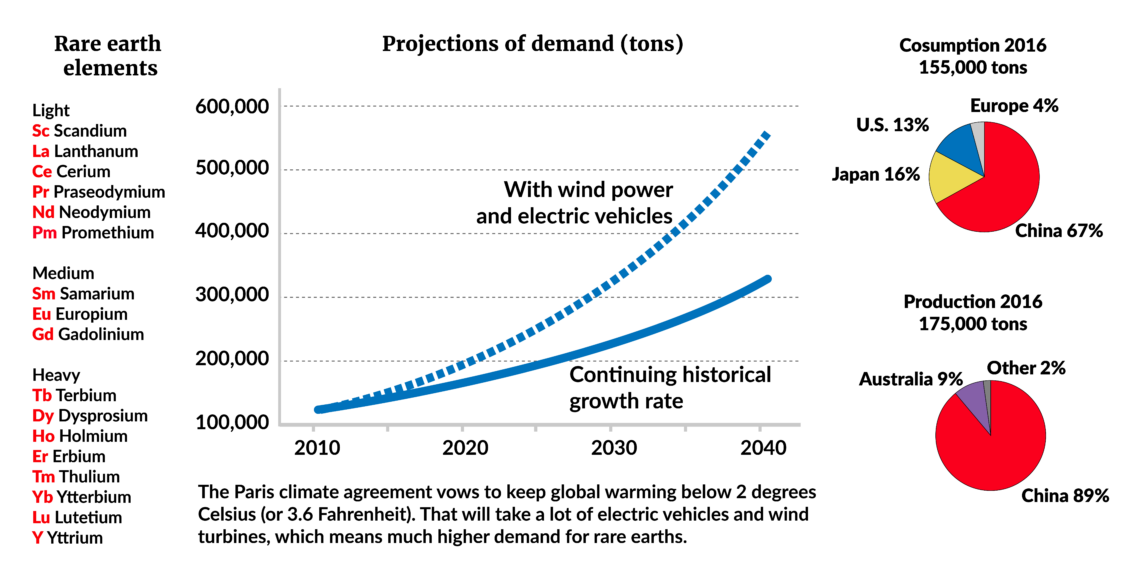

Rare earth elements are 17 silvery-white, soft, heavy metals that have numerous applications in electrical and electronic components. Despite their name, they are plentiful in the Earth’s crust, though some can be hard to find in pure form. Chemically, they are extremely similar, but they each have unique electromagnetic properties. The elements are generally divided into “light” and “heavy” groups (and sometimes “medium”) depending on their atomic weight. Both light and heavy rare earths are listed as critical raw materials by the EU.

In January 2021, Chinese media reported that Beijing was again considering export controls on rare earth elements and semi-finalized products therefrom, such as rare earth magnets. The announcement comes despite China having increased its production quota for rare earths by nearly 30 percent for the first half of this year. Last year, it raised its quota for rare earth mining to 140,000 tons – up from 100,000 in its new Five-Year Plan. It also increased its imports of rare earths to 47,000 tons (mostly from Myanmar, Malaysia and Vietnam). All these measures come as China tries to protect itself against new U.S. trade sanctions, but they also result from rapidly rising domestic demand for high-tech products.

Several of the 17 rare earth elements are almost exclusively extracted and processed by China, making them a severe supply risk for many countries. The rare earths market may seem small, at just $9 billion in 2015, yet industries that rely on these crucial materials are worth as much as $7 trillion.

Facts & figures

When the Chinese blocked exports of rare earth elements to Japan in 2010, the security of critical raw materials supplies temporarily attracted global attention. The situation now, however, is very different. Rare earths are crucial for new technologies. The rapid transition toward decarbonization, digitization, industry 4.0 and especially the demand for batteries for electric vehicles and energy storage make the need for them more pressing.

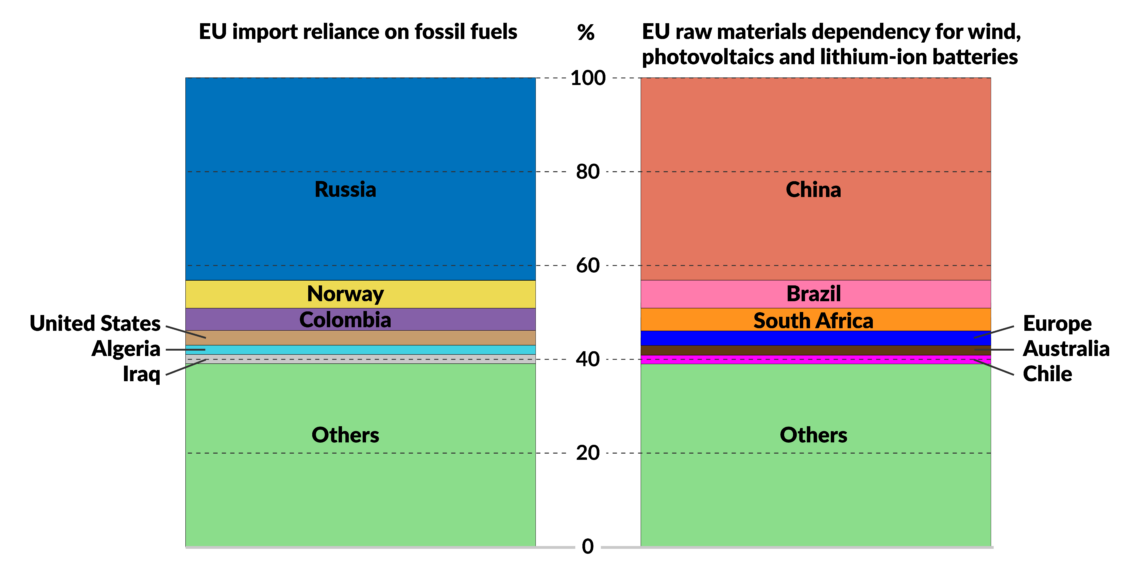

The ongoing energy transition will lead to a decrease in demand for fossil fuels starting in around 2030, as countries reduce their import dependencies and improve their supply security. Simultaneously, global demand for critical raw materials could drastically increase, creating new import dependencies and potentially even higher supply risks, opening up geopolitical vulnerabilities.

Facts & figures

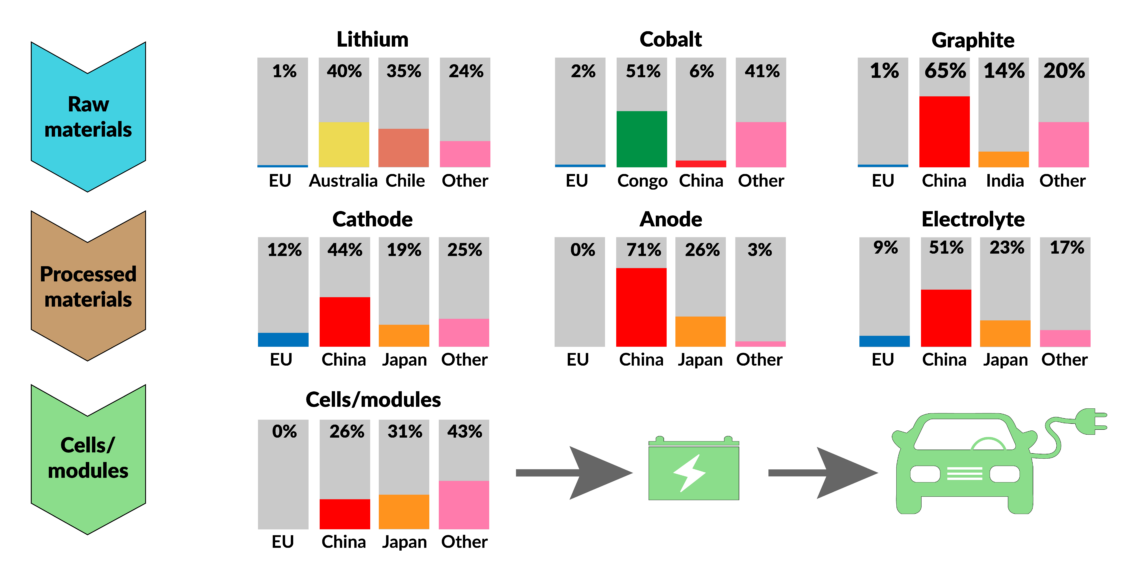

Rare earths are just one part of China’s dominance of global CRM supply. Along with 80 percent of rare earth production and more than 90 percent of refining processes, Chinese companies also control 80 percent of global refined cobalt production and more than 60 percent of worldwide lithium-ion manufacturing capacity. It is the only country to have positioned itself so strongly throughout the entire supply chain for environmentally friendly technologies, known as cleantech.

It usually takes 10 to 15 years to make new production chains operational, from opening mines to building the reprocessing and refining facilities. The question is what Europe and the U.S. could do between now and then to respond to tightening markets and increasing CRM supply insecurity.

Plans and projects

Back in 2018, European Commission Vice President Maros Sefcovic recognized the geopolitical and economic challenges on the horizon and warned that CRMs could become the “new oil.” Since then, Covid-19 has shown that the EU’s reliance on global supply chains is unsustainable, including for critical raw materials. The situation threatens to undermine the bloc’s living standards and its commitments to reduce its emission targets. Therefore, the Commission has begun pushing import diversification, investments in recycling technologies and the development of domestic mining, refining and processing capacities.

China provides 98 percent of the EU’s rare earths supply and around 62 percent of its 30 designated CRMs.

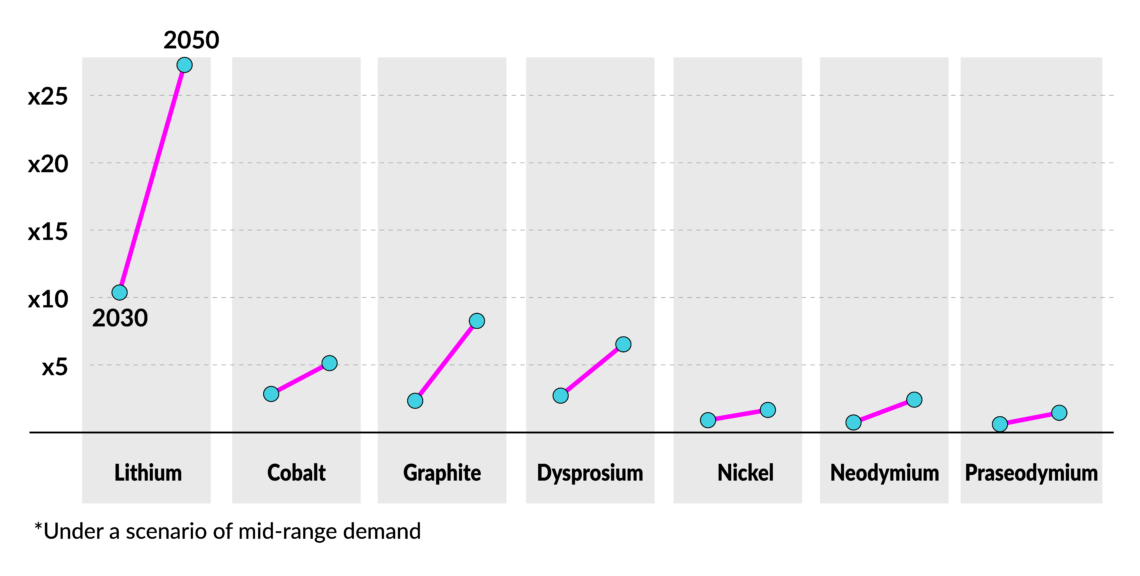

With the announcement of the European Green Deal in December 2019, the EU’s short- and medium-term demand for CRMs will rise. Just for electric vehicle batteries and energy storage, the European Commission has estimated that by 2030, it will need five times more cobalt and 18 times more lithium than it does now. By 2050, the growth in demand will reach 15 times and 60 times current levels, respectively. The Commission hopes the EU can become 80 percent self-sufficient for lithium by 2025 and expand cooperation on raw materials with Serbia, Albania, Ukraine and other countries with significant CRM reserves. (See also the figure below, which highlights the total EU demand growth for CRMs by 2030 and 2050.)

Facts & figures

China provides 98 percent of the EU’s rare earths supply and around 62 percent of its 30 designated CRMs. Many CRMs are difficult to substitute and are rarely recycled, magnifying the potential for supply risks.

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic showed that global supply chains are not flexible or fast enough to provide things like basic medicines, medical equipment and CRMs when demand surges and countries impose export restrictions. As a result, the EU has begun following a policy of “open strategic autonomy” and relocating some critical supply chains (including both mining and refining) to Europe to avoid “unwanted dependencies both economically and geopolitically.”

The rising concern was also reflected in the EU’s new list of CRMs, released in September 2020. The number of critical raw materials is now 30, up from 14 in 2011, 20 in 2014 and 27 in 2017. In the new list, lithium, bauxite, titanium and strontium were added. The addition of lithium had been expected due to the EU’s support for factories to mass-produce batteries for electric vehicles.

Facts & figures

There are already some new mining projects underway in Europe: for rare earths in Norway, cobalt in Finland and lithium in Spain, Portugal and the Czech Republic. In the United Kingdom, Pensana Rare Earths plans to build Europe’s first plant for processing rare earths (neodymium and praseodymium) for the manufacture of powerful magnets like those used in wind turbines and electric vehicles. Pensana hopes to capture 5-7 percent of the market. The UK government could provide the project with financial support as part of its 12 billion pounds “green industrial revolution” plan.

Facts & figures

CRM Action Plan

The EU has developed an “action plan” for a resilient, sustainable supply of CRMs. The strategy envisages:

- Developing resilient value chains for EU industrial ecosystems

- Reducing dependency on primary critical raw materials through circular use of resources, sustainable products and innovation

- Strengthening the sustainable and responsible domestic sourcing and processing of raw materials in the European Union

- Diversifying supply with sustainable and responsible sourcing from third countries, strengthening rules-based open trade in raw materials and removing distortions to international trade

In Norway, Norge Mining’s Bjerkreim Exploration Project offers another strategic opportunity. Recent geological modeling shows that the location contains more than 70 billion tons of mineralized rock, with one of the world’s most significant deposits of vanadium, titanium and phosphate (all on the EU CRM list). The most advanced exploration work is taking place at Oygrei, where studies have estimated some 1.55 billion tons of mineral resources could be extracted. The find highlights the significant role Norway can play in both the European and global markets for CRMs. When mining begins, it will be the first time vanadium and titanium are produced in Europe.

Facts & figures

Realistic strategy?

In the short term, battery demand is expected to increase by an annual rate of 40 percent between 2020 and 2025. The European Commission has ambitious plans to develop the EU’s own supplies of lithium, rare earths and other CRMs while diversifying its imports. While lithium, borate, and even some rare earths can be found in Europe, it is unlikely that any new mining projects will begin production within the next few years. Even then, there will still be plenty of other minerals for which Europe lacks sufficient deposits.

Domestic mining would be more environmentally friendly than importing CRMs from outside Europe, both due to laxer regulations and longer transport distances. Research has found that producing one ton of metal in China emits eight times more carbon than the equivalent process in Europe. Moreover, the European mining and refining industries have already decreased their carbon footprint by more than 60 percent over the past two decades.

Producing one ton of metal in China emits eight times more carbon than the equivalent process in Europe.

Nevertheless, the idea presents a difficult choice for some political interests within the EU. Environmentally focused organizations and green parties may be loath to support mining projects at home, even if they would bolster global efforts to reduce carbon emissions. The conflict could hamper the European Commission’s attempts to expand domestic CRM mining.

Scenarios

The EU, Germany and other member states have only recently begun addressing the CRM supply challenge more strategically. Their efforts are hamstrung, because the European Commission lacks the cohesive supranational power that would allow Europe to compete with China more effectively. Hence, it remains uncertain whether CRM mining can really expand in Europe or whether strict regulations, environmental concerns and public opposition will get in the way.

On the other hand, there is a growing trend toward subsidizing strategic supply chain projects to gain independence from China. This process can be seen in the U.S., Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea and even in the EU itself.

The strategic objectives of the European Green Deal and the expansion of renewables depend on an increased use and a reliable supply of CRMs. Europe lacks the abundant mineral deposits that the U.S. has. This limitation can be mitigated through the widespread introduction of reuse and recycling (referred to as a “circular economy”), reducing unsecured imports and expanding domestic CRM mining.

The economic changes wrought by the increasing demand for CRMs – and rare earths specifically – will have far-reaching geopolitical implications. They will alter supply chains and trade routes, creating new geopolitical rivalries and alliances. Ultimately, they will determine the EU’s global industrial prowess and geopolitical influence.