Can the West and China work together on climate change?

There is a widespread assumption in the Western world that China will fully cooperate in the global fight against climate change. But while Beijing appears genuinely willing to take the leap toward nonfossil energy, its path to carbon neutrality is fraught with challenges.

In a nutshell

- China intends to capitalize on its green policies

- It will likely reach carbon neutrality ahead of schedule

- However, Beijing still funds polluting projects abroad

China accounts for about 28 percent of carbon emissions worldwide. As the world’s largest CO2 emitter, it plays a crucial role in global climate politics. In 2020, President Xi Jinping declared that emissions would start to decrease in 2030, and that the country would reach carbon neutrality in 2060. The two promises gave hope to political elites around the world. But before determining whether the West and China can really work together, it is necessary to understand what led China to become a proactive player in climate politics, after having been hostile to the issue for years.

Beijing’s motivations

China’s climate policy has four aims: energy security, economic growth, international prestige and regime legitimacy. Energy security requires that most of China’s power consumption be produced domestically. Part of the reason why the country has used coal for so long is that the resource guarantees a domestic supply if all other alternatives are cut off. But now Beijing senses that the country is finally in a position to replace it with nonfossil energy in the near future.

Without an absolute cap on emissions in official documents, Beijing has given itself room to maneuver.

Economic growth has long been one of the overarching priorities of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Under President Xi, this means acquiring more advanced technology, including climate-friendly innovations, to generate profits and expand to global markets. China is gearing up to turn its climate efforts into a profitable business.

International reputation is especially important to Mr. Xi, all the more so after the CCP’s response to the Covid-19 outbreak was widely criticized. Beijing’s mask diplomacy and unfounded countercharges regarding the source of the pandemic have also hurt the Chinese leadership’s credibility. The CCP will have to play the climate card to improve its image, and the 14th Five-Year Plan reflects this intention.

Finally, President Xi understands that the legitimacy of the CCP is largely based on its performance in the eyes of Chinese citizens. Improving air quality and restoring ecological environments, like wetlands and woodlands, has boosted his administration’s popularity. As a result, he attaches more importance to greening China than his predecessors.

Despite these ambitions, China’s climate policies remain opaque and inconsistent. Given that Mr. Xi publicly committed to reaching carbon neutrality by 2060, one would have expected clear guidelines for reaching that goal. Yet the 14th Five-Year Plan only states that “energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) will be reduced by 13.5 percent and 18 percent respectively” – an ambiguous target. Without an absolute cap on emissions in official documents, Beijing has given itself room to maneuver. It is true that such vagueness could partly result from China’s dearth of reliable statistics. Ultimately, the matter will require political will. But President Xi appears determined to deliver on his promises.

Energy mix

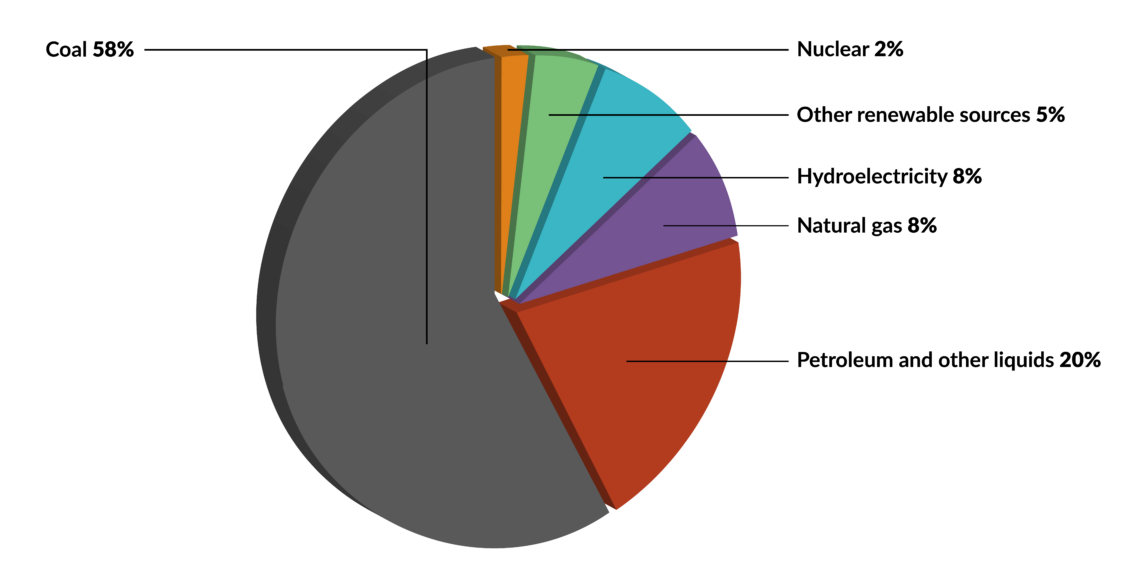

The CCP has said that it will likely make a clear announcement regarding China’s future energy mix in November of this year, around the time of the United Nations climate summit. However, China has already begun deploying various strategies to reduce its emissions. In 2019, China’s energy mix was 58 percent coal, 20 percent oil, 8 percent natural gas, 8 percent hydroelectricity, 5 percent renewable sources and 2 percent nuclear. In other words, the share of energy from nonfossil sources was only 14 percent that year, and has only increased by one percent in 2020.

It is estimated that the proportion of energy from nonfossil sources will be about 25 percent in 2030, and that the total wind and solar power capacity will reach more than 1.2 billion kilowatts. With significant adjustments in its energy structure, China could achieve a 50 percent renewable energy share by 2050. Expanding solar and wind energy is one of the pillars of the 14th Five-Year Plan. The National Energy Administration (NEA) recently issued a document stating that the share of wind and solar power in total domestic consumption will reach about 11 percent in 2021. China has yet to make use of the full potential of its wind farms and solar power generation facilities, and the cost of these technologies keeps dropping. A paper published in Nature in May 2020 estimates that non-hydro renewable sources could account for 62 percent of Chinese electricity production by 2030.

Facts & figures

However, the Chinese government urgently needs to address arrears in subsidies for non-hydro renewable energy, mainly solar and wind power, which amounted to $45 billion in 2019. Having realized the seriousness of this shortfall, Beijing could solve it by the end of the current five-year plan, in 2025.

As of 2019, China was only using 44 percent of its hydropower resources. The set target for the share of hydroelectricity in the country’s energy mix is 18 percent. But China could even overshoot this target and reach 20 percent soon. However, these types of exploitation projects are often carried out with economic gain in mind, rather than ecological consequences, particularly downstream.

Beijing also sees nuclear energy as an important means to partially replace coal in the medium and long term, especially in areas where solar and wind power are scarce but industry is concentrated, like central and southern China. Nuclear power generation is expected to reach 10 percent of the energy mix by 2030, and 13.5 by 2035. Currently, nuclear power accounts for 4 percent of electricity generation in China.

Since 2017, Beijing has been aggressively promoting gas as an alternative to coal for both electricity and heating. In 2019, the world average share of natural gas in primary energy consumption was 24.4 percent, compared to only 8.1 percent in China. With two pipelines from Russia in place, the amount of imported natural gas will increase in the short and medium term. Although China is rich in shale gas, wide scale extraction is unlikely because the necessary technology is lacking. Like with hydropower development, ecological concerns are often put aside in this process.

China expects that the West will transfer its green technologies, preferably for free.

China’s coal-fired power capacity should decline as its emissions reduction targets become more rigorous. Still, according to official Chinese data, the country’s CO2 emissions increased by about 2 percent in 2019. In June 2019, the China Electric Power Planning and Design Institute warned that, to avoid power shortages in the next two to three years, 16 Chinese provinces should build new generation capacity. As a result, the NEA has approved 48 gigawatts of new coal power projects in the first five months of 2020, more than the volume installed in all of 2019, in the name of energy security.

In response, a central government inspection team criticized the NEA in January 2021, and the latter promised to respond by reporting to the State Council within 30 working days. It is not yet known whether the approved coal power projects will be suspended. The international community sees it as a litmus test of whether the Chinese government is serious about keeping its promises, since building new coal plants would seriously hinder the country’s chances of reaching carbon neutrality by 2060.

Other measures

By the end of 2019, China had carried out several carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) projects. Beijing claims major breakthroughs have been made in several core technologies. But the high economic cost of such innovations is limiting their development. On January 5, 2021, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment released a document on a united national market related to carbon emission trading. More than 2,000 power generation enterprises are now included in the national market, which means the first step toward including the power generation sector in the national carbon trading market has been taken. However, the long-overdue expansion of the carbon trading market to other industries (like steel and aviation) seems to be delayed again this year.

In addition, the People’s Bank of China is only starting to design a blueprint for green finance. At this pace, it will take another three to four years to establish a comprehensive carbon trading market that includes several major emitting industries. There are other ways China could reduce its emissions. The current aggressive development of electric vehicles and the China Fusion Engineering Test Reactor, still in the experimental stage, could also help cut greenhouse gases.

Difficulties in cooperation

Many American and European commentators say climate change is an area where China can cooperate with the West. This view is overly optimistic. There are many obstacles to be overcome before successful collaboration can be established, and so far Western countries have not tackled them adequately.

China’s clean energy plan could be hampered by a risky attack to reclaim Taiwan through force.

One example is the Chinese government’s proposal to implement hydropower development in the Yarlung Tsangpo River, in Tibet. The reservoirs built there will generate three times as much power as the Three Gorges Dam. But the river flows into the Brahmaputra River in India and the Jamuna in Bangladesh. Both countries fear the dams will give China control over the water flow, like with the Mekong. The United States and the European Union may struggle to navigate this delicate political situation.

Also, China expects that the West will transfer its green technologies, preferably for free. Its wish list is long: advanced technology for electric vehicles, tools for running low-carbon cities, energy efficiency innovation, smart transportation, CCUS and so forth.

Moreover, China has built and is building coal-fired power plants for several countries as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. Though it has not announced any plans to curb overseas construction of such facilities. Beijing did recently cancel funding for coal plants in Bangladesh – a rare occurrence due to international pressure.

Scenarios

In the best-case scenario, China will continue to develop its non-hydro renewable energy, which will be supported by an entirely new ultra-high voltage grid and hopefully growing storage technologies. Yearly coal consumption will drop to about 2.7 billion tons by 2028, in comparison to 4.86 billion tons in 2019. Carbon emissions will begin to decline after 2028, later than many Western countries hope. In the case of speedy decarbonization, China will probably achieve carbon neutrality by 2055, five years ahead of target.

The world should prepare for China’s ascent to global leadership in clean energy. Beijing will promote its “energy internet” concept by pushing its own products, like grid technology, to gain a greater share of the global market. But events could also take a darker turn. China’s clean energy and emission reduction plan could be hampered by a risky attack to reclaim Taiwan through force, triggering a regional war.

Also, because of domestic factors, China’s decarbonization efforts may not go smoothly. As a result, Beijing would probably try to shift the blame on other large emitters, like India.