China’s liberalization dilemma

China’s economy is being weighed down by several factors. Now, Beijing faces a dilemma: enact more liberalizing reforms, and sacrifice its grip on the economy, or content itself with stagnation.

In a nutshell

- China’s economy is slowing down

- Liberalization would help it return to fast growth

- Keeping tight control over business will hold it back

Beginning in 1978 and throughout the 1990s, China undertook epoch-defining liberal economic reforms in preparation for its accession to the World Trade Organization. Its economy took off, empowering its ascent to great power status. Then, around 2005, the reform impulse began to wane. By the time Xi Jinping had risen to General Secretary of the Communist Party (CCP) in 2012, China’s liberalization period was essentially over. Alarmed by the prospect of a private economy beyond its control, President Xi has doubled down on the role of the state.

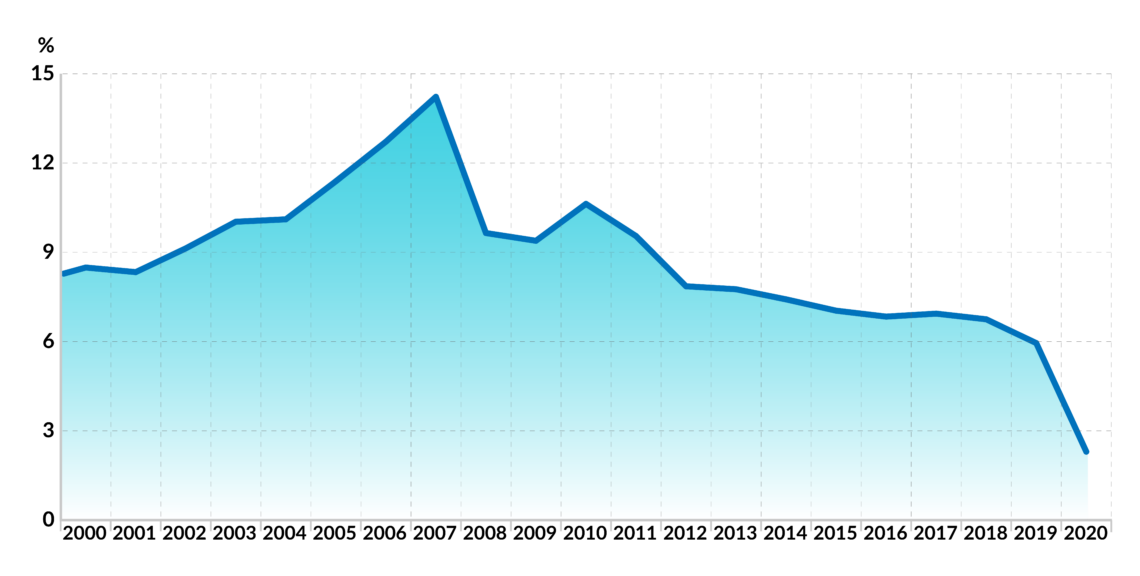

At the same time, Mr. Xi has presided over growth rates that are low (by Chinese standards) and declining – from just under 8 percent when he took office to just under 6 percent in 2019. The Chinese economy is currently in the midst of a slowdown, related to but predating a spike in Covid-19 cases.

The problem is that China has extracted most of the value it could from plentiful, cheap labor and cheap capital – the things that drive developing economies. Its labor pool is drying up. Even many Chinese companies are looking abroad for less expensive options. China is entering a period where it must derive more value from gains in efficiency.

China has been in transition for 27 years.

This is a classic developing-country problem. Only about a dozen nations have ever successfully cleared that hurdle. Several of them are in Asia: Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea. It took all four of these countries more than 20 years to make the transition. They did it through liberalization. China has been in transition now for 27 years. And yet, it is heading in the other direction.

Take state-owned enterprises (SOEs). According to Rhodium Group’s China Dashboard – which tracks reforms across 10 measures that the Chinese themselves identify as necessary – the efficiency of SOEs has “not improved” over the last five years. Their presence across industries “barely changed” in the same period. In key industries, a category including telecommunications, shipping, aviation and rail, SOEs account for more than 80 percent of revenues. In what Rhodium calls “pillar” industries, including chemicals, electronics, and equipment manufacturing, their share of revenues comes to 45 percent.

Facts & figures

The government is also reasserting control over the private sector – weighing it down with political objectives that distract from its core economic responsibility of maximizing returns. The government’s sabotage of the financial technology firm Ant Group’s initial public offering in 2020 and ride-hailing company Didi in 2021 were the most high-profile examples of the lengths the party is prepared to go when its political mandates are not met.

On financial reform, Beijing has long been reluctant to allow the market to allocate capital. For good reason, because if capital were free to come and go, much of it would leave China. Only by increasing the cost of capital could Beijing prevent that from happening. And doing this would restrain the government-directed development that legitimizes CCP rule.

China is lagging in necessary land, trade and labor reforms as well. To be clear, China’s economy is “open,” to the extent that it is tied to global financial markets and supply chains. It has made strides in making business easier and is a much less severe violator of intellectual property rights than is popularly portrayed (although it may be the most significant). But more efficient regulation of business is not the same as liberal reform.

China faces a dilemma: do the things that will enable it to continue growing at the robust rates of the past, thereby sacrificing some government control, or content itself with lower rates of growth that mean economic stagnation. How China decides will have major geopolitical consequences.

Scenarios

Scenario 1: Positive outlook

In the lead-up to next fall’s Communist Party Congress, Chinese politics will be focused on jockeying for position, not reform. But what if the party uses the inevitable change in leadership circles (whether or not it affects President Xi’s position as General Secretary) and expression of future direction to recommit to liberal economic reform?

If it does, China will lock in the 6-7 percent growth rates it has long been saying it wants. Liberal economic reforms will entail a loosening of government control over the economy, and unavoidably, a relaxation of political control. China will not become a multiparty democracy. But in pursuit of the free flow of information and debate required by modern economies, as well as the arbitration of domestic interests, Chinese governance will turn toward “consultative authoritarianism.” This means less direct control by the government, greater civil society participation, and more autonomy for the private sector.

That change will take the ideological edge off China’s competition with the United States, with Washington’s democratic allies in Asia, and with Europe. Greater concern for the flow of international capital and the impact that confrontational foreign policy has on these flows will rein in aggressive international displays of nationalism. Tech supply chain issues will become less contentious and economic interdependence more palatable to its partners.

China will maintain its national security interests, as they have roots deeper than communist party ideology. Issues like Taiwan independence tap into a nationalism that a more consultative Chinese government will not supplant. It will, however, find less confrontational ways of managing its interests. With Taiwan, it would reconcile itself to formal unification always being just over the horizon, rattle fewer swords, and return to the goal of gradual integration that characterized the 2008-2016 period.

Absent a cooperative government in Taiwan, China will remain patient. The South China Sea dispute and dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands may find workable, tension-lowering accommodations. Efforts like the Belt and Road Initiative will become more easily reconcilable with the interests of international partners, as will its efforts to establish leadership in international bodies.

Beijing will remain sensitive to what it views as threats from the U.S, and it will prepare to counter them. But cooperation, both with the U.S. and others, will better characterize China’s involvement in global affairs than confrontation.

Scenario 2: Most likely

In this scenario, China’s concern for firm political control continues to lead it away from liberalization. As a result, its economic performance stagnates. None of the above referenced positive changes in Chinese behavior occur – just the opposite.

China becomes more ideologically driven at home, reins in its private sector, and searches for autonomous solutions to supply chain challenges. Fed by concern over its military capability and aggressive diplomacy, these challenges develop into the long-predicted tech decoupling – especially in areas with security implications. China remains one or two steps behind the cutting edge in most fields, while its search for innovation leads it to greater reliance on espionage, further compounding tension with the U.S.

China would retain enough technological capability, however, to present an ever more serious military threat. It does not have to incorporate the most advanced defense technologies to degrade the credibility of U.S. commitments to the region – especially after the shambolic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and long-term questions over U.S. government defense budgets. At the same time, regional militaries will remain technologically and operationally inferior to the Chinese and unable to present a united opposition to Chinese designs.

In this scenario, concerns over debt lead to less Chinese capacity for international investment – a trend already on display since 2017. China prioritizes markets important to obtain secure sources of commodities, like Africa, and its immediate neighborhood, especially Southeast Asia.

These trends both narrow the scope of the Chinese threat and intensify it. In the worst case, a miscalculation over the U.S. security commitment to the western Pacific region and international reaction to Chinese military adventurism leads to outright war.

After the 2008-2009 financial crisis China determined that in the competition with the U.S. and Western ideas of international order, time was on its side. Since then, this judgment has only been reinforced. To Beijing’s way of thinking, even in the context of sustained economic stagnation, there is no reason to change its priorities and behavior. Chinese party control, its most important priority, can be maintained without taking the risks entailed in liberal economic reforms.