The burgeoning China-Russia axis

Bad news for Ukraine and the West: in 2023 Beijing crossed the Rubicon in China-Russia political, economic and military cooperation.

In a nutshell

- A China-Russia geopolitical alignment was long the Kremlin’s dream

- The war in Ukraine has brought the two autocratic powers much closer

- The axis is emerging just as the West is preoccupied with domestic issues

China’s foreign policy today shows it has aligned more closely with Russia. Beijing also is intensifying its cooperation with the emerging powers of the Global South and digging deeper into its confrontational anti-American and, generally, anti-Western position.

China’s President Xi Jinping has made Russia his most important strategic partner. Also, he is using the Belt and Road Initiative and other economic and political levers at his disposal to pull the Global South into China’s orbit and expand its influence in the United Nations.

The pro-Russia faction in China’s ruling elite, which is currently the dominant one, rejects all measures that smack of Western values and governance systems. Nevertheless, China continues to need Western capital, technology and markets, so it aims to maintain relations with Western countries while working to undermine the existing international order. Beijing’s refusal to heed the landmark 2016 ruling of an international tribunal in The Hague that dismissed China’s claim to much of the South China Sea stands as a prime example of this strategy at work.

‘Strategic coordination’

Alignment with Russia is now a stated priority of Chinese foreign policy, even if Chinese diplomats avoid saying so to their Western counterparts at international meetings. It was the message of the videoconference that President Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin reportedly had on the eve of China’s New Year. In China’s Foreign Ministry readout, the leader in Beijing stated that China and Russia should “strengthen strategic coordination,” safeguard their “national sovereignty, security and development interests” and “resolutely oppose external interference in their internal affairs.”

While the pro-West faction wilts, members of the pro-Russian camp prosper in China’s diplomatic and the military spheres.

Until Mr. Xi arrived in power in 2012, decades of reforms under his predecessors had versed China’s administrative and technical elites in approaches somewhat close to Western management philosophy. But since President Xi has moved politically closer to President Putin, the pro-Russian faction, relatively weak a few years ago, has caught traction and remains entirely in line with the leader’s political choices. The Chinese Communist Party’s code of conduct dictates that he should enjoy absolute obedience.

While the pro-West faction wilts, members of the pro-Russian camp prosper in China’s diplomatic and the military spheres, including the defense industry. A China-Russia tandem is no longer a flight of fancy. A typical case has been the recent promotion of Dong Jun as China’s new defense minister. A former navy commander in the critical South China Sea region and a Russian language speaker, Mr. Dong had been handpicked by President Xi for training at the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, Russia’s top military institution.

Xi Jinping’s U-turn

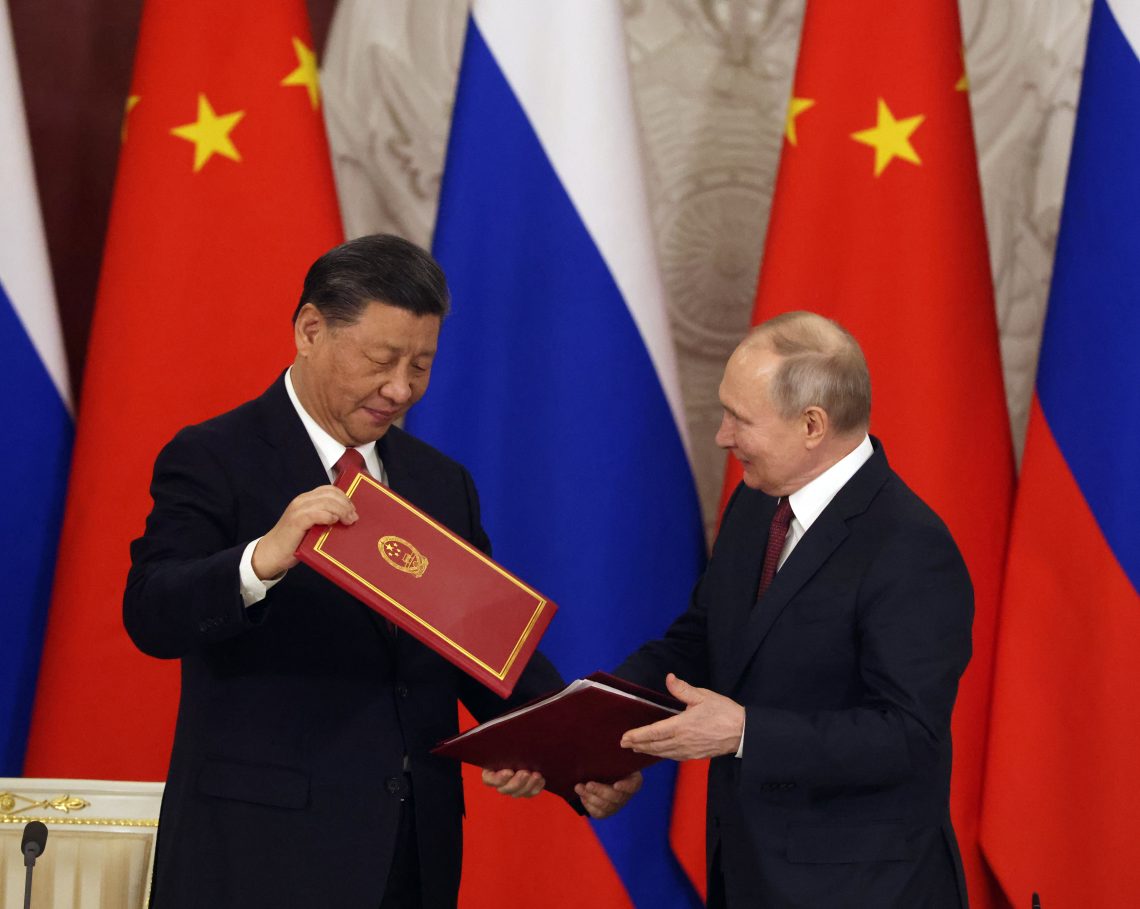

President Xi’s diplomatic tightening of the relationship with Moscow was announced immediately before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. On February 4, 2022, at the start of the Winter Olympic Games in Beijing, the two presidents briefly met there to reiterate earlier Chinese Foreign Ministry statements that there were “no forbidden areas,” no ending date and no upper bound in their cooperation.

When the 2022 invasion into Ukraine began, the pro-Russian faction seemed to have plenty of confidence that Russia would quickly capture Kyiv. The Chinese embassy in Ukraine was in no hurry to evacuate the Chinese students studying there; when the hostilities began, the diplomats merely advised the students to leave the country by car and handed out Chinse flags for citizens to mount on their vehicles so as not to be targeted.

Read more on China-Russia cooperation

China’s military alliance prepares for confrontation

China has not condemned Russia’s aggression and has abstained during United Nations votes on it. Soon after the invasion started, however, Moscow’s campaign stalled, its prospects became uncertain, and President Xi began to worry about China’s dependence on technology, markets and capital, and took steps to shore up the relationship with the West, especially Europe. Beijing launched its “smart diplomacy” offensive in 2023, trying to avoid being cast as Russia’s accomplice in the war and present itself as a neutral mediator. Li Hui, formerly China’s ambassador to Russia, was dispatched to Kyiv as Beijing’s “special representative for Eurasian affairs” to meet Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy. From there, the envoy went to Moscow.

Another interesting development was related to Phoenix TV, an important Chinese-language media outlet. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, it has had a special envoy embedded with frontline Russian forces. In May 2023 year, however, the station added a female reporter, Chen Ying, to cover the war in Ukraine with the Ukrainian army, in line with the so-called neutral diplomacy. The Ukrainian side expressed its appreciation of that.

Then the tide turned. According to Politico and Nikkei Asia, President Putin was alarmed by President Xi’s decision to mediate in the Ukraine war, seeing it as a move by the pro-Western, pro-U.S. camp in China’s foreign ministry. He reportedly decided to tip President Xi off about a worrisome development in his inner circle. Mr. Putin dispatched a trusted official to tell Mr. Xi that his protegee, Foreign Minister Qin Gang, had allegedly leaked secrets to the United States. Mr. Gang ended up removed and never heard from again, and a swift purge among Beijing’s highest officials followed. And after the unlucky minister’s disappearance, China’s leader has again changed his stance on the Ukraine war.

Li Hui disappeared for a while as a peace envoy, and the female reporter from Phoenix TV was ordered home from Ukraine. Since these memorable (if still somewhat murky) events, China’s neutrality rhetoric on the war in Ukraine merely serves as a diplomatic equivalent of a heat shield. Meanwhile, there have been significant upgrades in many areas of the China-Russia relations.

Flourishing Sino-Russian relations

In the trade sector, China-Russia exchange in goods and services hit a record high, $240.1 billion in 2023, a 26.3 percent increase over the previous year, well above the annual targets set by the two governments. However, China’s trade with both the U.S. and Europe is lower than it has been in years. In an effort to make up the difference, China has significantly increased its trade with Global South countries.

Shipments of dual-use equipment and industrial products from China have measurably contributed to Russia’s war effort.

And there has been an uptick in China-Russia military cooperation. Even if much of the made-in-Russia war materiel has lost its luster in the Ukrainian battlefields, access to Russian weapons matters for Beijing, since it sees some of Russia’s cutting-edge military and space technologies as worth acquiring. In return, Russia expects China to share at least some of the technological marvels it steals from the West. So far, this has been a sore point between the two countries. In contrast to his North Korean ally, President Xi does not officially provide “lethal aid” to Russia to ensure a continued presence of major Western firms in China and avoid Western retribution. However, shipments of dual-use equipment and industrial products from China have measurably contributed to Russia’s war effort.

The mutual assistance is also reflected in the intensified cooperation between the Chinese and Russian navies in the Sea of Japan, the Taiwan Strait and even the South China Sea. The two naval forces have conducted several joint exercises and patrols. That may also have significant implications for President Xi’s ambition of bringing Taiwan – peacefully or otherwise – back into the Middle Kingdom’s fold.

China’s appointment of the new defense minister looks like a harbinger of tightening military cooperation. Minister Dong Jun’s first public engagement after taking office was a video call to his Russian counterpart, Sergei Shoigu. As the Russian News Agency TASS reported, Mr. Shoigu heard from Mr. Jun: “We have supported you on the Ukrainian issue despite the fact that the U.S. and Europe continue to put pressure on the Chinese side. Even defense cooperation between China and the European Union is [now] threatened, but we will not change or abandon our established policy course over this. And they should not and cannot hinder normal Russian-Chinese cooperation.”

With the rise of the pro-Russia camp, the anti-U.S. and anti-West ressentiment in China has grown. This also has to do with Beijing’s perception of the external environment. Political instability and distrust between Republicans and Democrats in the U.S., the economic downturn in Europe and the strengthening of President Putin’s relations with North Korea and Iran (which has been supplying drones and ammunition to Russia) have been, in effect, weakening Ukraine’s geopolitical position.

As Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has passed the two-year mark, Beijing’s pro-Russian faction may begin to believe again that Moscow will eventually prevail in the war.

At this juncture, it looks like the China-Russia alignment may have reached a point of no return, at least during President Xi’s tenure. The relationship is likely to keep expanding, as the leader of China appears to have decided to move away from close interactions with Western governments.

However, as President Xi has demonstrated on several occasions, China still has limits to what it is willing to do for Russia. Beijing is not ready to cut all ties with Western capital, technology and markets to meet Moscow’s expectations. China has secretly been helping Russia circumvent Western financial sanctions. Lately, however, the Chinese banks that have ties with Russia have become very concerned about doing business with sanctioned Russian companies, as that could expose them to secondary Western sanctions. Zhejiang Chouzhou Commercial Bank, very important for Russian exporters to China, and a number of other banks stopped doing business with Russia and Belarus due to such concerns. Officials in Moscow can only hope that the transfers through the Financial Messaging System, the Russian equivalent of the Swift transfer system, will continue unimpeded. Both sides are now looking for ways to sustain the bilateral trade.

Persisting Western illusions

On January 14, 2024, in the run-up to the World Economic Forum in Davos, host Switzerland and Ukraine welcomed some 120 national security officials to drum up support for the 10-point peace plan for Ukraine put forth earlier by President Zelenskiy. And in early February, during a session of the Sino-Swiss strategic dialogue in Beijing, the Swiss side reiterated its idea of a global peace conference. As of this writing, the Chinese had yet to respond.

It is hard to imagine that EU member states or the U.S. would sacrifice their economic and security interests in exchange for Beijing’s half-hearted bid to help Ukraine.

Apparently, Ukraine and the countries of Europe are still counting on China to use its influence on the president of Russia in ways that would be helpful to Ukraine. The presence of Chinese Premier Li Qiang at the Davos event fueled optimism about Beijing playing a pivotal role in the talks with Russia.

These hopes are unlikely to be realized. President Xi is not ready to return to the posture of feigned neutrality that China’s diplomacy adopted in the first half of 2023. Beijing will not partake in a Swiss-sponsored peace conference nor play a mediator between Russia and Ukraine. China might eventually be interested in Ukraine’s reconstruction, but President Xi will not risk repeating last year’s situation, which made Mr. Putin unhappy.

Presumably, Beijing expects a quid pro quo if the West wants something from China, such as opening the EU market fully for China-made electric vehicles and other strategic products. It is hard to imagine, though, that EU member states or the U.S. would sacrifice their economic and security interests in exchange for Beijing’s half-hearted bid to help Ukraine. The hypothetical concession would also need to be extended to Russia. Moscow, no longer fearing a rout in the Ukrainian battlefields, would almost certainly demand ending the Western military supplies to Ukraine as a precondition. No self-respecting power in the West could succumb to such demands.

Scenarios

During the Covid-19 pandemic, President Xi memorably claimed that China’s radical “zero-covid” policy would be carried out until the disease was eradicated in the country. Then, after nearly three years of lockdowns and quarantine, the Chinese leader made a sudden policy U-turn in the face of mounting public protests and epic economic costs. Similarly, Beijing in late 2023 signaled that China had no interest in being part in peace talks proposed by Ukraine and the West, and maintained it had “limited influence” on the two fighting sides. But something apparently has changed, and in late February 2024, China’s foreign ministry announced that the special envoy, Mr. Hui, would embark on “the second round of shuttle diplomacy” and go to Ukraine, Russia, Germany, France, Poland and Brussels to “find a political solution to the Ukrainian crisis.”

Beijing as a peace broker, part 2

This renewed interest in brokering peace talks may be related to China’s alarmingly worsening economic outlook. President Xi badly needs the West to open its profitable markets to advanced Chinese products, and the EU is very high on its wish list. However, unlike its previous attempt at mediation, Beijing is not going to surprise President Putin with its diplomatic activity and, presumably, it will heed Moscow’s interests in the talks.

The question now is what the future of the China-Russia alignment will be and how this complicated international situation can develop. Much may hinge on the coming U.S. presidential elections. If former President Donald Trump returns to power, global tensions, already considerable, could increase further. Mr. Trump is perceived as more ready to accommodate Russia and less critical of President Putin than the European leaders would like to see. Many find this alarming, as NATO’s European allies largely depend on the U.S. for strategic security – the arrangement that Mr. Trump has consequently questioned.

Combined with the EU’s deepening economic troubles and political instability, Mr. Trump’s presence in the White House weakens the West’s hand vis-a-vis Russia and China, which shows in the eventual peace negotiations. Ukraine’s failure to defend itself against Russian aggression also encourages President Xi to step up his pressure on Taiwan and further strengthen the pro-Russian camp in China.

Less likely: Gradual improvement

The U.S. election results leave American society badly divided, but the state machinery continues to work, and the country’s isolationist temptation is tamed. U.S. aid to Ukraine continues but is significantly reduced. Across the Atlantic, the EU manages to solve its energy problems, tackles inflation and its leading economies pick up, boosting Brussels’ self-confidence – and, significantly, the output of Europe’s ammunition factories. Ukraine shores up its war economy and successfully executes its asymmetric high-tech defense strategy, making Russia continuously suffer and look for a way out with an increased sense of urgency. All this provides a shot in the arm for the pro-Western faction of the Chinese Communist Party. Fearing that his friend Vladimir may suffer more misfortunes, President Xi offers to resume his role as a go-between for Russia on one side and Ukraine and the West on the other. Mr. Putin accepts the talks under China’s umbrella.

In both these scenarios, the U.S. policies are a crucial factor.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.