China, Latin America and the new space race

China has been ramping up cooperation with Latin America and the Caribbean as part of its strategic goal to gain space supremacy.

In a nutshell

- China is rapidly expanding space cooperation with Latin America

- Beijing is attempting to create new structures parallel to those of the U.S.

- Space geopolitics will become increasingly divided

Over the last two decades, China’s relations with Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have evolved beyond their largely extractive character to encompass a growing focus on digital and space technology.

The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) first white paper on its relations with LAC, released in 2008, referenced outer space only in passing. “The Chinese side will strengthen cooperation with Latin America and the Caribbean in aeronautics and astronautics … and other areas of shared interest,” it read. Eight years later, China’s interest in the sector had grown. Section 9 of its 2016 policy paper on LAC – the latest issued – explicitly addressed space cooperation, with emphasis on remote sensing and communication satellites, satellite data application and aerospace infrastructure. These themes have since been picked up by the CCP’s Global Security Initiative introduced in 2022 and outlined in February 2023.

For China, the pursuit of space cooperation with Latin America and the Caribbean advances its wider objective to dominate near-earth space. It also strengthens ties with strategic regional partners, and undercuts Western and American-led alliances and institutions. While some LAC governments share Beijing’s political motives, others are encouraged by the space industry’s economic benefits. All of this suggests that China-LAC space relations are likely to deepen in the years ahead.

History of space cooperation

The first joint space venture between China and the LAC region dates to 1988, when the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite (CBERS) program was established.

CBERS was a collaboration between the China Academy of Space Technology and Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research. It was created to collaboratively develop satellites and launch them into orbit, with the declared aim of observing and monitoring the earth’s resources and environment. The initiative was meant to allow the two countries to expand their footprint in space without the United States’ or Western involvement. To date, six CBERS satellites have been launched: in 1999, 2003, 2007, 2013, 2014, and most recently in 2019. As of 2002, each country covers 50 percent of the costs; previously 70 percent had been covered by China.

Encouraged by its successful collaboration with Brazil and its space race with the U.S., the CCP has expanded its space-based partnerships throughout the LAC region.

Bilateral space relations

China’s most significant advances in bilateral space cooperation with LAC states have been with populist regimes that share China’s worldview and are often in need of financial assistance and unable to obtain it from the West.

On the heels of its 2003 financial crisis, Argentina signed a framework agreement for space cooperation with Beijing in 2004. Signed between Argentina’s National Space Activities Commission and China’s National Space Agency, it centered around the use of China’s Long March rockets to launch Argentine satellites from the then-newly established national satellite company, Argentina Satellite Solutions Company. In this regard, it also served as a precursor for the development of the Espacio Lejano Station, in Neuquen province, Patagonia.

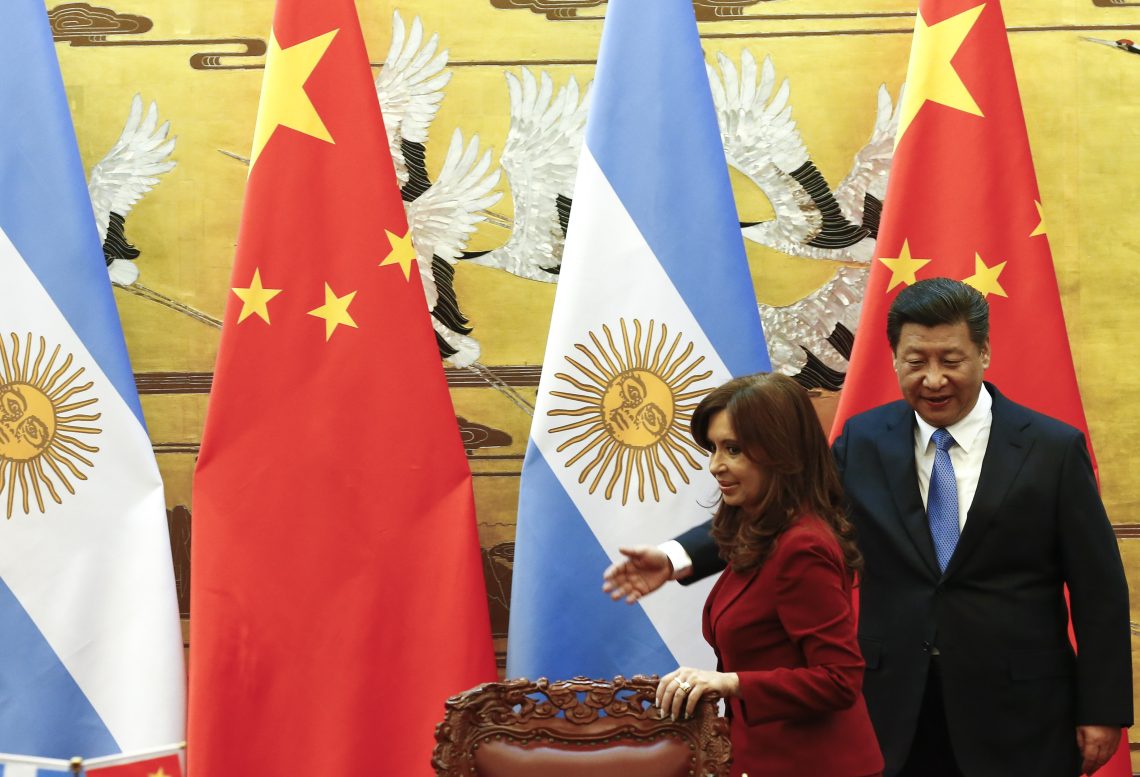

The station, with its 35-meter-diameter antenna and operations run by the China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General, a division of the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force, remains something of an enigma. Agreed to in 2014 by President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and Chinese President Xi Jinping, and made operational in late 2017, it appears to be a dual-use facility – utilized for Chinese civilian and military purposes. Some analysts suggest it could have been involved in the Chinese spy balloon that appeared in U.S. airspace earlier this year. Yet absent transparency and Argentine oversight, this cannot be confirmed.

The $500 million facility, which is part of the Chinese Deep Space Network, is Beijing’s first deep space earth station outside of the mainland. It is designed to facilitate communication between deep space missions and spacecraft that pass over the southern hemisphere. Chinese state media claimed it “played an important role” in the Chang’e 4’s 2019 landing on the far side of the moon. It is also integral to China’s Mars research and its plans to improve multi-objective tracking, telemetry, and command capabilities (MTTC), which would allow for more coordinated communication in complex missions. Improved MTTC capabilities would also enhance the PLA’s battlefield awareness, navigation, and positioning.

China has also established bilateral space relations with Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Venezuela. To date, all cooperation has centered around the provision of Chinese launch services, satellite components and platforms, mostly financed by loans secured through the China Development Bank. Such capabilities have enabled LAC countries to monitor their natural resource and agricultural activity – including for export to China. It has also allowed them to improve telecommunications and collect geospatial data that could assist with border surveillance and other matters of national security.

For Beijing, bilateral space cooperation with LAC states forms part of its Space Information Corridor, a component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) intended to enhance space-related cooperation and data sharing among BRI members through the deployment of satellites, ground stations, data centers, other ground application systems and the training of foreign space personnel. LAC countries with bilateral space relations with China are nodes in Beijing’s wider space network, which is being forged to dilute and ultimately supplant its U.S.-led counterpart.

Regional initiatives

China’s Global Security Initiative (GSI) explicitly declares its support for the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) in “playing an active role in upholding regional peace and security.” Since 2011, Beijing has demonstrated its preference for working with the LAC region through CELAC, even though the bloc lacks the institutional mechanisms to address matters of either security or space. China’s support for CELAC comes at the expense of the Organization of American States (OAS), the region’s traditional architecture for multilateral engagement. While the U.S. is a member of the OAS, it is not a member of CELAC.

China deliberately seeks to forge new structures for cooperation rather than work within existing ones. This also extends to space. The 2022-2024 China-CELAC Joint Action Plan proposes the establishment of a China-CELAC Space Cooperation Forum through which members would collaborate on satellite technology, remote sensing, and research. The plan also notes Beijing’s aim to leverage the BRI to extend its Beidou satellite system throughout the region as a way to rival the U.S.- operated Global Positioning System.

In 2021, Mexico and Argentina spearheaded the establishment of the Latin American and Caribbean Space Agency (ALCE), headquartered in Mexico. Currently comprising 23 member states (Brazil has not joined), the ALCE is designed to foster regional collaboration on space-based activities, including the development of the LAC region’s own satellite technology. With an initial budget of $100 million, however, it remains to be seen what the initiative will be able to accomplish.

China has openly expressed support for the ALCE. Although to date no formal agreements have been brokered, Beijing’s financial and technological backing of the agency cannot be discounted. Among ALCE member states are those with which Beijing already boasts bilateral space relations, as well as those disposed to closer ties with it. Engagement through the ALCE would provide China with an additional vehicle to expand its space footprint in Latin America, as well as to induce LAC country participation in its own multilateral space initiatives.

LAC states in China’s multilateral space initiatives

In recent years, Beijing has embarked on the creation of new formal and informal multilateral initiatives designed to rival the policy tasks of existing ones. Of these, several center around space. They have become increasingly important to CCP policy – including in its dealings with LAC states. The China-CELAC joint plan, for example, invites CELAC states to “join the International Lunar Research Station”(ILRS) being developed with Russia. In April, Venezuela expressed interest in doing so “as soon as possible.”

Since the China National Space Administration released its initial road map for the ILRS in 2021, it has signed cooperation agreements or letters of intent with Argentina and Brazil, as well as the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization to which Peru belongs. Brazil’s interest in the ILRS is noteworthy, as it could complicate its participation in the U.S.-led Artemis Accords, to which Mexico and Colombia are also signatories. Brazil’s president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, has openly voiced his intention to foster closer ties with Beijing to “balance world geopolitics.”

In April, Beijing announced the establishment of the International Lunar Research Station Cooperation Organization (ILRSCO). Unlike the Artemis Accords, which is a nonbinding multilateral agreement, the ILRSCO is to be forged as a formal organization with leadership and bureaucracy, both likely to come from China. Through agreements on principles and subsequent planning led by Beijing, the ILRSCO will pursue lunar missions in coordination with member states. Its creation risks leading to a two-system lunar governance.

More on space geopolitics

Beidou: Assessing China’s alternative to GPS

Eyeing Taiwan, China builds its own Starlink

For LAC countries, participation in the ILRSCO and other Chinese-led space initiatives might provide access to resources and space-based navigation, positioning and communication infrastructures. For those that share Beijing’s objective of a multilateral world order, it has the added benefit of normalizing and extending Chinese global governance.

This aim underpinned the 2005 founding of the Beijing-based Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO). Peru is a founding member and Mexico is an observer state. “Past experience shows that during the Cold War years, space policies of superpowers … rested … on rivalry, claiming hegemony in space,” reads APSCO’s founding statement. Article 6 of its convention outlines cooperation in space technology, earth observation, space law, research, and a “central data bank.” Peru is party to several of these activities. It hosts a space observation site for monitoring debris in low-earth orbit; with China, Turkey, and Pakistan it is party to the Joint Small Multi-Mission Satellites Constellation Program; and it has participated in training around APSCO’s data-sharing service platform.

Peruvian involvement in APSCO, like that of other LAC states in Chinese multilateral space initiatives, indicates an evolving space geography beyond the LAC region but one in which its members are increasingly invested beyond the more obvious bilateral engagements. Encouraged by Beijing, LAC member states are becoming increasingly active players in space geopolitics.

Scenarios

The trajectory of Sino-LAC space cooperation appears poised to intensify both through bilateral and multilateral channels, especially among the region’s left-leaning governments. LAC regional space initiatives are likely to remain too embryonic to be credible actors.

Beijing will continue to aggressively pursue this deepening of space relations as it seeks strategic global partners to advance its agenda. For LAC countries, such ties could eventually come at the expense of space cooperation with the U.S. The adoption of the Beidou system, ground stations such as Espacio Lejano, and data-sharing agreements with Beijing are increasingly likely to be perceived as national security threats by the U.S. While for some LAC countries such an ostensible shift away from the U.S. would be welcome, for others it would prompt technological and diplomatic challenges.

In this context, Brazil under President Lula is a country to watch. Brazil and the U.S. have in place, among other initiatives, a Space Situational Awareness sharing agreement that facilitates information exchange on space objects. Should Brazil agree to the ILRSCO, for instance, this and other U.S. space programming could be curtailed. For Brazil and moderating LAC states, then, space policy is becoming a balancing act between established and emergent actors. The financial and technology advantages associated with space cooperation with China make it unlikely that it would be abandoned.

As China deepens space cooperation in the LAC region, it becomes an ever-more capable and multidimensional space actor with the ability to shape space norms. Its engagement in the region also buoys member countries as credible space actors. This will contribute to increasingly multipolar, labyrinthine, and for the West, adversarial space geopolitics.