China’s superpower pragmatism in Southeast Asia

Though China is perceived as trying to supplant the U.S. as the global superpower, in reality, Beijing wants to carve out a sphere of influence in Eurasia and Africa. Whether it can attain this role of “junior superpower” will depend on the success of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In a nutshell

- China’s ambition to become a “junior” superpower hinges on the BRI

- Big, debt-inducing infrastructure projects are being met with resistance

- China is changing its approach, making such initiatives more collaborative

Discerning visitors can see why the United States has locked horns with China over trade and technology. Standing in downtown Beijing or Shanghai and being dwarfed by their skyscrapers yields a sense of awe. In less than two generations, the Chinese have nearly caught up with the Americans, leapfrogging them in notable ways. Just as gleaming Manhattan in New York City once symbolized the U.S.’s economic prowess and confident cosmopolitanism, the newer, equally modern Beijing and Shanghai are giving China’s global rival a run for its money. Seen from this perspective, it is unsurprising that Washington is pushing back against China for taking advantage of the international economic system that the U.S. has built.

This grounded view can be projected into geopolitical and geoeconomic terms. China, as the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump sees it, wants to supplant the U.S. as the preeminent global superpower.

The Chinese leadership has a different perspective. Their Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), for example, is predominantly designed to expand China’s sphere of influence over Eurasia and parts of Africa. Its involvement is much more limited in North America, Latin America and the Caribbean, where the U.S. has long dominated.

China is determined to be second-to-none on what it sees as its turf but may be willing to be a “junior” superpower to the U.S. on the broader global stage. Influential Chinese thought leaders, such as Yan Xuetong, who described China’s global role as such in a Foreign Affairs article earlier this year, have been expounding China’s junior superpower aspiration without sufficient U.S. notice.

Opposition to the BRI

To be sure, China’s superpower role in international affairs will hinge on the BRI, a colossal infrastructure project formally known as the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The BRI is huge in size and scope, straddling the Eurasian landmass and waterways from the South China Sea through the Indian Ocean to eastern Africa, with an estimated long-term price tag to the tune of $900 billion or more. Yet China’s monumental geostrategic developmental project across oceans and continents has been around for just under six years.

Unsurprisingly, China’s BRI has not gone down well with partner countries. Like its other ventures, such as the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation initiative around the Mekong River in mainland Southeast Asia and weaponized artificial islands in the South China Sea, China has a tendency to shape outcomes as faits accomplis, and then expect others to adjust to them.

China may need to become more consultative, listening to others and incorporating what they say into decision-making processes. Ramming infrastructure projects down the throats of BRI partners has proven counterproductive, undermining China’s global stature as it tries to stand its ground in relation to the U.S. Evidence suggests the Chinese are learning by doing, making it up as they go along with the broad BRI blueprint in mind.

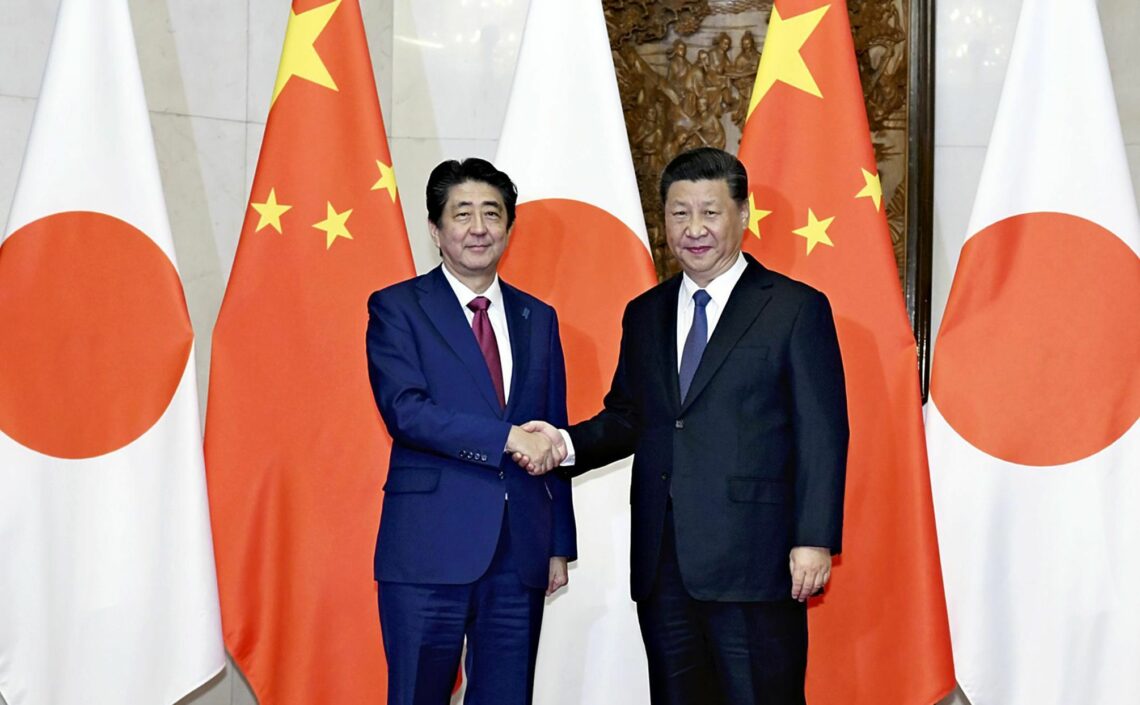

President Xi’s visit to Japan later this year is expected to further promote a new China-Japan realignment.

Moreover, Washington’s growing unilateralism has forced China to change certain elements of the project. Beijing now appears more conciliatory toward countries in its perceived sphere of influence: it cannot afford geostrategic battles on too many fronts. A clear example of this new approach is China’s softening relationship with Japan. Thanks to the Trump administration’s belligerence in the U.S.-China trade war and go-it-alone geopolitical style on Korean Peninsular issues, a China-Japan realignment through third-country cooperation appears to be in the offing.

China has shown interest in alternative types of development cooperation because the BRI has faced stiff opposition among partner countries, which have been concerned with the so-called “debt trap” for borrowing more than they can pay back. One of the new cooperation models that has emerged is the “China-Japan Third Country” approach. China has found this alternative compelling because its BRI investments have declined markedly. For example, in 2018, China’s Belt and Road development in Southeast Asia for big-ticket projects (those over $100 million) dropped by 49.7 percent to $19.2 billion, the lowest in four years.

China-Japan cooperation

The global pushback against the BRI has been compounded by the U.S.-China trade conflict, which posed greater risks for Chinese economic expansion. At the same time, U.S. moves against China have put pressure on America’s partners to toe the line. Japan, a long-standing U.S. treaty ally, has shown interest in hedging its bets by working with China because it considers the Trump administration as decreasingly reliable in its role as Japan’s security guarantor. The first Japan-China Forum on Third Country Business Cooperation last October was a salient manifestation of the shifting geopolitical sands in mainland Southeast Asia.

The forum was held in Beijing and featured a high-profile visit by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, along with his Economy Minister Hiroshige Seko and Foreign Minister Taro Kono. The Chinese side was represented by Premier Li Keqiang, Commerce Minister Zhong Shan and National Development and Reform Minister He Lifeng. About 1,400 people attended, including top executives of leading industries from both sides.

The visit produced 52 memoranda of cooperation between the two countries, among government agencies, companies, economic associations and other entities. These agreements ranged widely from infrastructure and distribution to IT, healthcare and finance. For Thailand, which is a U.S. ally by treaty and close friend of both China and Japan, the critical outcome was the cooperative agreement known as the China-Japan-Thailand “smart city” pilot project.

At the forum, Kanit Sangsubhan, secretary general of Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) project, along with Amata Corp. founder and CEO Vikrom Kromadit, made a pitch for Thailand as an investment hub. Mr. Kromadit played an instrumental role because he knew Chinese managers at his Amata City industrial estate in Rayong province. From his collection of contacts, Mr. Kromadit was able to propose a linkup between Nanjing, China and Yokohama, Japan for an environmentally friendly smart city project in Chonburi province, which is part of the EEC. The initiative is just getting off the ground; a successful workshop was held in March 2019.

Geopolitical shift

The smart city project in Thailand reveals three important developments. First, China’s planners are aware that the BRI is facing headwinds and needs to be recalibrated. Working in a tripartite format may be a safe and productive fallback option, even if it requires putting aside differences with a former foe like Japan.

Second, for Japan, working with China in view of its rise and geopolitical tensions in the East China Sea may not be easily palatable but worth the risks. As the U.S. becomes less predictable under President Trump, who has ratcheted up his rhetoric against China, Japan may not want to see Beijing backed into a corner for fear of repercussions. China could overreact and/or Japan may be forced to take sides.

China may need to become more consultative, incorporating what others say into decision-making processes.

Third, for Thailand, this is a win-win proposition, whereby the role of key individuals – Mr. Kromadit in this case – was indispensable. He was able to bring Chinese firms on board for a China-Japan scheme, with keen backing from the EEC. If it proceeds as planned, this pilot project could showcase China’s willingness to adjust and Japan’s ability to accommodate. However, the jury is out on whether and to what extent this kind of tripartite setup can be linked to the BRI and China’s economic corridor in mainland Southeast Asia. Conceivably, China-Japan cooperation (through third parties and the smart cities scheme) could gain momentum regardless of how well the BRI succeeds.

Plans are afoot for similar China-Japan third-country cooperation in Laos. Apart from the smart cities project, this tripartite approach may expand into transport and logistics, and energy and environment. A follow-up China-Japan-Thailand meeting in Bangkok in early April 2019 solidified what Prime Minister Abe began in Beijing last October. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s planned participation in the G20 meeting in Osaka, Japan in June this year (the Chinese leader’s first visit to Japan since 2013) is expected to further promote a new China-Japan realignment and cooperation in third countries.

None of this portends a complete and irreversible warming of bilateral relations between the two East Asian powers, but it does represent a geopolitical shift in view of the Trump administration’s unilateralist tendencies. Japan is looking after itself more in this regard, with a record defense budget for 2019 of $47 billion. And China is showing that it can listen and play the role of stakeholder, not only regional master and commander.

Scenarios

Two major scenarios follow from these trends. In the first, China learns to be a pragmatic superpower, enabling it to carve out a sphere of influence along the BRI’s contours, marginalizing the U.S.’s role while selectively accommodating Japan. In this scenario, Japan would be a junior power to China in East Asia, while China would willingly be a junior superpower to the U.S. globally.

The second scenario envisages the U.S. coming back into East Asia more aggressively through its allies like Japan, South Korea and the Philippines, and through partners and friends like India, Vietnam and Indonesia, under the geostrategic framework of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific. This scenario suggests the U.S. wants to retain its global supremacy in absolute terms, not yielding to any Chinese sphere of influence created by the BRI.

In both scenarios, the smaller states and societies would have to hedge and may be forced to choose sides: China’s pragmatism is limited and the U.S.’s appetite for unilateral retribution will grow during President Trump’s likely second term.