China’s nuclear weapons buildup

Beijing is expanding its nuclear arsenal across land, air and sea and could one day rival American or Russian capabilities.

In a nutshell

- Beijing is developing a nuclear triad and new strategic weapons systems

- There are also signs of an evolving nuclear doctrine

- An expanding arsenal would give China more sway over regional issues

For decades, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been involved in an unprecedented military modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the collective name for its armed forces. China’s effort to modernize its nuclear (also known as strategic) weapons program is of particular concern to analysts and policymakers in Asia and much of the West.

Beijing is undertaking a significant expansion and diversification of its nuclear forces. In recent years, China has been developing a nuclear triad comprising land-, sea- and air-based forces. Moreover, the construction of hundreds of new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos and advancements in novel nuclear-capable weapons have raised further concerns about the country’s nuclear doctrine.

In an era of intensifying great power competition, primarily involving the United States and China, these developments pose questions about the future of peace, stability and security in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond.

Silo development

The last few years have seen a surge in the PRC’s land-based ICBM nuclear forces, housed in underground silos and on mobile launchers and falling under the command of the PLA’s Rocket Forces (PLARF).

China had been assessed to possess approximately 20 ICBM silos and 100 road-mobile ICBM launchers, with an operational nuclear warhead count in the low 200s. These numbers have begun to change rapidly. Today, it is estimated that the PRC is constructing at least 300 additional ICBM silos in three new missile fields in the northwestern desert. According to a 2023 Pentagon assessment, China now has more ground-based (fixed and mobile) ICBM launchers than the U.S.

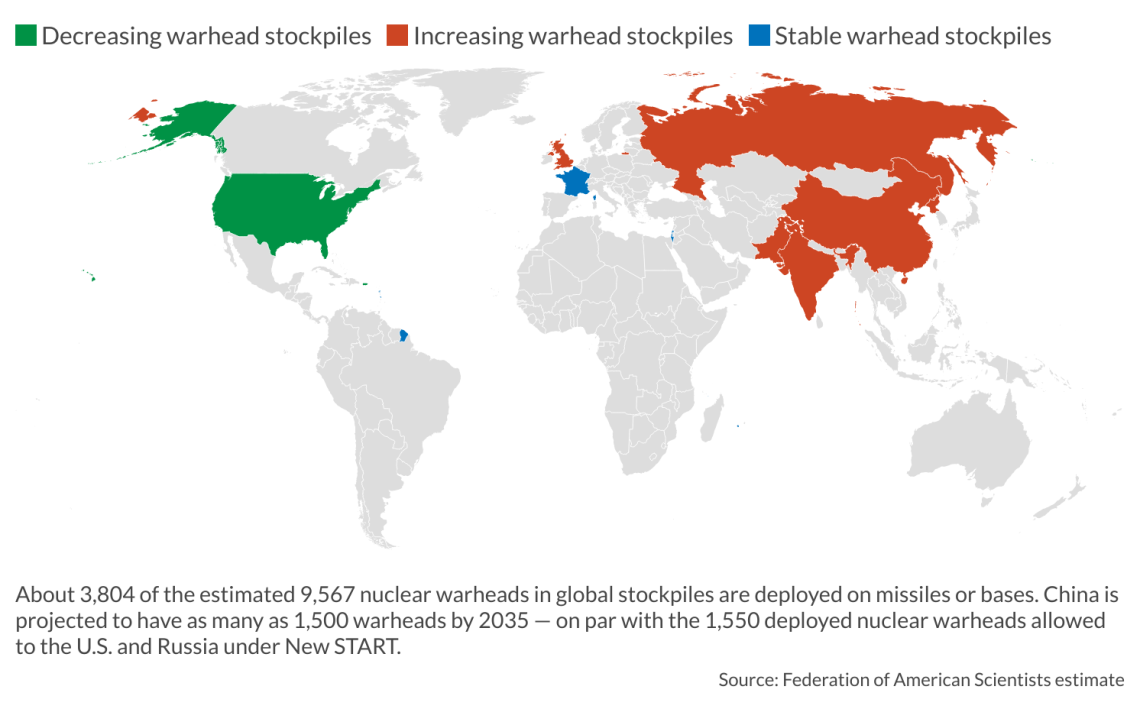

Even more worrying, these new Chinese silos could house the PLARF’s most modern ICBM, the DF-41, which is reported to carry as many as three multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) per missile. Given China’s estimated 400 nuclear warheads, it is projected to have as many as 1,000 warheads by 2030 and 1,500 by 2035. These figures would place the PRC on par with the 1,550 deployed nuclear warheads allowed to the U.S. and Russia under the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START).

Supporting this analysis is the report that China is now building, with Russian assistance, fast-breeder nuclear reactors that will produce plutonium, a fissile material that is the preferred fuel for modern nuclear weapons.

Read more on nuclear weapons

The threat of nuclear war

Triad and beyond

China has historically relied primarily on a limited number of ICBMs based in fixed, land-based silos and mobile launchers capable of retaliatory strikes against opponents initiating an attack. In recent years, however, this has begun to change. Indeed, China’s nuclear force of a few hundred land-based missiles has evolved from a land-based monad to the development and operational deployment of a land/sea/air-based nuclear triad, creating a nuclear force similar to those of the U.S. and Russia.

The PLA Air Force (PLAAF) is adding a strategic mission to its conventional capabilities. Beyond modernizing Soviet-era bombers, the PLAAF is developing a new long-range strategic bomber with stealth characteristics.

The PLA Navy has also sent a Chinese nuclear deterrent and strike force to sea. It now operates six nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBN). Each SSBN can carry 12 missiles with an intercontinental range, and more SSBNs are being constructed. Such a force provides Chinese leadership with a mobile, stealthy and highly survivable undersea nuclear deterrent and strike force that may eventually rival the American and Russian subsurface capabilities.

Facts & figures

Beyond the traditional nuclear triad, Beijing is also developing new strategic weapon systems, such as a fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS) armed with a hypersonic glide vehicle. A weapon with unlimited range, the FOBS would be launched from a land-based platform, propelled through the atmosphere and into space before reentering the atmosphere en route to its designated target.

The glide vehicle poses a significant threat due to its high speed – at least five times the speed of sound – and maneuverability. The FOBS could be armed with a conventional or nuclear warhead, possibly more than one.

Some PRC security strategists have voiced an interest in low-yield nuclear weapons, which could provide the PLA with “asymmetric capabilities that could be employed coercively during an escalation crisis, similar to Russia’s irresponsible nuclear saber-rattling during its war against Ukraine,” as recently observed by U.S. Air Force General Anthony Cotton, the current Commander of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM).

These developments, from new silos to new platforms, will significantly enhance the credibility, survivability and effectiveness of the PRC’s nuclear deterrent and strike force if deployed at the predicted numbers and capabilities.

‘Strategic breakout’

The changes in the quality and quantity of Beijing’s nuclear arsenal could drive an evolution of its nuclear doctrine, diverging from China’s long-standing “minimum deterrence” and “no-first-use” strategy.

Beijing has long believed that its relatively small nuclear arsenal was adequate for deterrence. If necessary, China would have the capability to retaliate against an adversary’s military, civilian population or economy with a second strike from its surviving nuclear forces. Indeed, the expected growth in China’s nuclear arsenal could give it a first-strike capability, enabling the Chinese leadership to conduct a massive nuclear strike on an opponent to preempt or prevent a conventional military or nuclear attack during a crisis or conflict.

Another doctrinal issue of concern is the reported incorporation of a launch-on-warning alert status for China’s nuclear forces. As described in U.S. assessments, this is known as “an early warning counterstrike,” in which “warning of a missile strike leads to a counterstrike before an enemy first strike can detonate.”

As U.S. Navy Admiral Charles Richard, recently the commander of U.S. STRATCOM, warned in 2021:

“We are witnessing a strategic breakout by China. China’s explosive growth and modernization of its nuclear and conventional forces can only be what I describe as breathtaking. And that word, “breathtaking,” may not be enough. I know there’s been a lot of discussion on why they are doing this. Let me just say right now, it doesn’t matter why China is and continues to grow and modernize. What matters is that they are building the capability to execute any plausible nuclear employment strategy, the last brick in the wall of a military capable of coercion. And keep in mind, China is treaty-unconstrained and can field whatever they want.”

If realized, these emerging Chinese atomic abilities will give Beijing greater international prestige, influence, power and freedom of action. It will also deliver political and military leverage over other countries, including the U.S., Russia and rising (nuclear power) India, a regional rival.

Indeed, these developments could enable China to influence, constrain, coerce or compel diplomatic and security outcomes involving Taiwan’s political future, peace on the Korean Peninsula and freedom of navigation around the South China Sea, among other ongoing geopolitical issues.

Scenarios

Limited Chinese buildup, and new arms control regimes

Though currently unconstrained by any nuclear arms control agreement, Beijing could seek negotiations with Washington (even including Moscow) to limit the superpowers’ nuclear arsenals. A tripartite arms control pact on nuclear weapons would aim to limit the size of the nuclear stockpiles and the number and types of nuclear delivery systems of the three parties.

Indeed, in support of global nuclear arms reductions efforts, including the 1972 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, such an agreement could even decrease the stockpiles of the three parties below those currently mandated under the U.S.-Russia New START, which is set to expire in 2026, at 1,550 deployed warheads.

From Beijing’s perspective, achieving a reduction by Washington and Moscow below New START levels would eliminate the need for China to match existing American and Russian nuclear force levels, thereby saving significant defense spending that could be used for other military modernization programs.

However, given Beijing’s reluctance to enter into any serious, high-level arms control discussions on nuclear matters so far, particularly with Washington, and its concerns about allowing anything to limit the growth of Chinese power, especially military power, this scenario is unlikely.

China as a nuclear peer and a new arms race

Under a more probable scenario, the PRC continues its nuclear buildup with numbers and capabilities that rival – or even exceed – the operationally deployed nuclear warheads of the U.S. and Russia, the world’s current preeminent nuclear powers.

Despite entreaties from the international community, Beijing could refuse to enter into arms control talks with Washington or Moscow, due to concern that joining discussions before achieving near-parity, parity or superiority would at a minimum put China at a negotiating disadvantage and possibly move Beijing into a position of temporary, or even permanent, nuclear and military inferiority.

Continuing its nuclear buildup, especially surpassing the quantity and or quality of the American and Russian nuclear forces, would also enhance China’s international status and influence in the military, diplomatic, economic and informational arenas as it pursues great power status.

Despite the risk that this unprecedented shift in the global nuclear hierarchy could not only bring instability, but nuclear and conventional arms races and nuclear proliferation beyond China, Russia and the U.S., this scenario is the most likely outcome of Beijing’s bomb buildup.