The next wave of mass migration

Extreme weather events are likely to become the main cause behind waves of immigration toward Europe.

In a nutshell

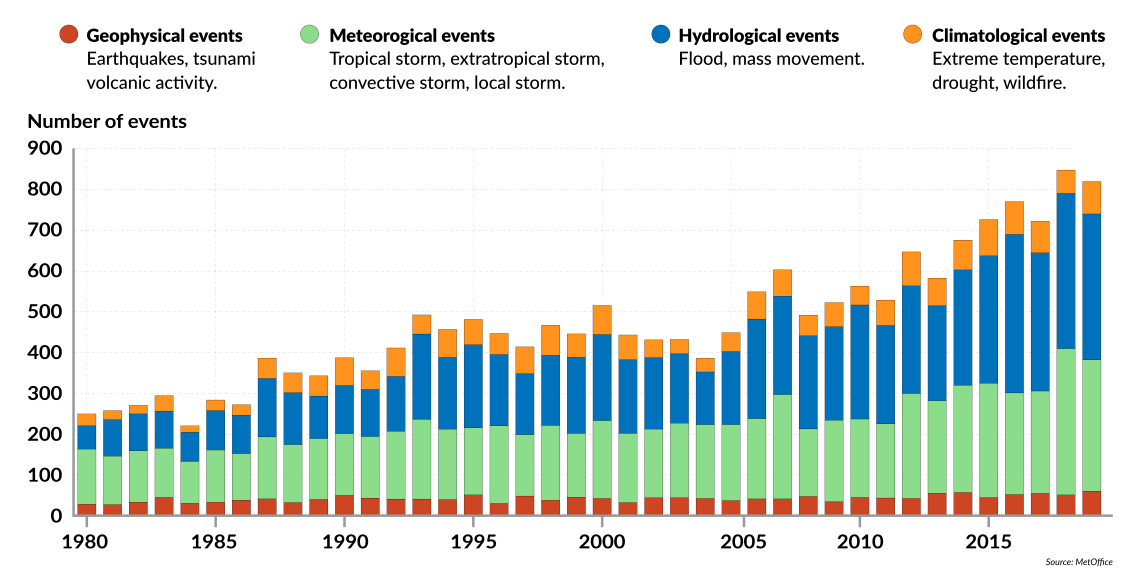

- Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent

- Africa is disproportionately affected by this phenomenon

- Large segments of displaced populations will migrate to Europe

This report is the first in a two-part series on migration from GIS Expert Dr. Federica Saini Fasanotti. The second part focuses on Europe’s response to new migration challenges.

Hurricane Ian, which disrupted the lives of millions when it swept over the Gulf of Mexico in late September this year, will not soon be forgotten. Torrential rains and winds of up to 240 kilometers per hour produced an extraordinary surge that flooded not only coastal areas but also their hinterland.

At the same time, Typhoon Noru was slamming into the Philippines. Earlier this year, Hurricane Fiona formed near Puerto Rico and hit Canada with unprecedented force, and Typhoon Nanmadol drove 9 million people to evacuate from their homes in Japan. Typhoon Merbok devastated Alaska with waves more than 50 feet high. Pakistan saw dramatic floods, aggravated by melting local glaciers. Leaving as much as one third of the country underwater, and more than 1,600 people and 800,000 livestock dead, the disaster will change the face of Pakistan for decades. The United Nations has called these phenomena the footprint of climate change.

Climate change and migration

Although Africa’s 54 states have not contributed significantly to the global emissions that accelerated climate change, the continent is one of the hardest hit. Desertification, dust storms and rising sea levels are poised to wreak havoc on large segments of the African populace.

By 2100, Africa is expected to account for 40 percent of the global population, which will grow to 11 billion. There will likely be 2.5 billion Africans by 2050. Amar Bhattacharya of the Brookings Institution writes that this growth will require an extraordinary increase in investment in “three critical areas: energy transitions and related investments in sustainable infrastructure; investments in climate change adaptation and resilience; and restoration of natural capital (through agriculture, food and land use practices) and biodiversity. … Altogether, Africa will need to invest around $200 billion per year by 2025 and close to $400 billion per year by 2030 on these priorities.”

Water will become a commodity over which wars are fought.

African governments will be the first line of defense to safeguard the continent’s biological heritage, such as the rainforest of the Congo River Basin, which like the Amazon is crucial to removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Africa’s worst climate-related changes in recent decades are not hurricanes, but rather a persistent drought. The near extinction of Lake Chad is a prime example, as are the widening of the Sahel desert belt southward and the increasingly long periods without rain throughout the Maghreb. The population will grow but rainfall will decrease, thus rapidly shrinking the amount of arable land. And temperatures will rise – in a continent where only half of the 1.2 billion residents have access to electricity.

If these trends continue unchecked, much of Africa will ultimately become uninhabitable. In the Lake Chad basin, 5.3 million people (mostly fishermen and farmers) were displaced by climate-related changes. Experts predict that Africa’s glaciers will disappear: those of Mount Kenya by 2030 and those of Mount Kilimanjaro by 2040.

Already, small rural communities in the Maghreb struggle to produce enough to subsist. The same goes for intensive agriculture, which in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, generates up to a fifth of gross domestic product. Even slight disruptions will have exponential effects on those societies.

Facts & figures

The rise of extreme weather

In an area where water availability is already limited, population growth will drive not only an increase in demand for water but also accelerate desertification, barring significant investment in creating a viable supply. Here, advances in technologies hold great promise, from space-based surveillance to AI-supported genetic modification of crops to make them more resistant to drought and heat.

Rising sea levels will exacerbate the problem for coastal cities, river mouths and deltas by salinizing estuaries. Water will become a commodity over which wars are fought.

Fortress Europe

Between 2015 and 2016, Europe was subject to uncontrolled migration flows, recording nearly 1.5 million arrivals. Migrants came mainly from Africa, creating a deep political crisis among European governments. The most notable consequence was the partial suspension of the Schengen Agreement. Even though fewer people arrived via the three classic Mediterranean routes in the following years, many European states continued to carry out border checks (in part because of the Covid-19 pandemic). But, in 2022 the number of migrants seeking to enter Europe is on the rise again.

It will become increasingly difficult, and in some areas impossible, to grow crops and raise animals.

It is estimated that in 15 years, more than half of Africa’s 375 million young people will live in rural areas. These are the same areas that will be most affected by climate change. They will be forced to migrate to urban centers, but existing cities will not be able to accommodate such numbers. They will have no choice but to migrate.

Scenarios

As climate-related phenomena become more frequent, the number of internally and externally displaced persons in Africa will grow. In the Horn of Africa area, some 1.2 million people have been displaced already, largely because of floods, storms and droughts. The World Bank’s 2021 Groundswell report states that, due to climate change alone, 216 million people could migrate internally by 2050. Climate migrants will outnumber labor and security migrants, historically the most prevalent.

There are three scenarios for North Africa alone: pessimistic (13 million internal migrants by 2050), moderate (9.9 million) and optimistic (4.5 million). To these numbers, the rest of the continent must be added. Of these millions of internal migrants, hundreds of thousands, if not millions, will attempt to cross the Mediterranean.

Rising temperatures will have a far-reaching impact: the loss or even extinction of animal and plant species with the disappearance of entire ecosystems, including marine environments that are fundamental to the survival of fishing communities.

It will become increasingly difficult, and in some areas impossible, to grow crops and raise animals. This will be devastating for those who do not have the means to invest in the technology needed to cope with drought and higher temperatures. Food security will be profoundly affected. Societies will face major economic crises as a result, which, in turn, will create political instability. Once again, the most vulnerable segments of these populations – the poorest, minorities, women and children – will inevitably bear the brunt of the crisis.