The Philippines’ policy and the great power competition

Philippine foreign policy drivers go beyond the theatrics of its current president. Simultaneous economic cooperation and territorial conflict with China is a timeless foreign policy matter. But there are even deeper sources of the Philippines’ international behavior.

In a nutshell

- The Philippines-U.S. relation is full of seeming contradictions

- The same is true of Manila’s complicated rapport with Beijing

- Philippine foreign policy hinges on the country's history and traditions

Philippine foreign policy has its unique drivers. It is something more than a product of the great power competition. These drivers are more enduring than the current theatrical President Rodrigo Duterte – who is, in fact, a manifestation of historical trends, not an aberration. The Philippines’ reactions to events in its neighborhood and the alignments the country makes with other powers derive as much from its past as the current events.

History’s burden

In 2019, President Duterte declared an official holiday in honor of Filipino independence leader Emilio Aguinaldo, an adversary of both the Spanish and American imperialists who became the country’s first president. The move was not without critics at home, but it serves to underscore the way Filipinos see themselves. Americans still sometimes call the brutal war they fought in the Philippines in 1899-1902 an “insurrection,” as if the Filipinos were seceding from a constitutional union. In the Philippines, the struggle is remembered as the second phase of the country’s war for independence.

That the Filipinos lament their historical loss to the Americans does not make Filipinos anti-American. Polling consistently shows them to be among the most pro-American people in the world. However, it does mean that fierce independence is an inescapable part of the Philippines’ collective political psyche. This trait has endured despite the Philippines’ experience of more than 100 years as an American territory, status as an American commonwealth and Cold War alliance with the U.S. – as well as the extremely close personal ties between the peoples of the two countries.

The phenomenon finds a perfect illustration in President Duterte’s defiance of American criticisms over his “war on drugs” and the popularity this defiance receives in the Philippines.

The presence of American troops in the Philippines has long been an issue in Philippine politics.

The Filipino sense of national pride and love of America have always existed in uneasy tension. Occasionally, the tension has snapped. Examples include resentment of U.S. support for Philippines strongman Ferdinand Marcos in the 1980s, the 1992 expulsion of the U.S. military from its bases in the Philippines, Manila’s withdrawal from the Iraq War’s “coalition of the willing” in 2004, and the mid-to-late 2000s controversy over the alleged rape of a Filipino woman by U.S. Marines near the former Subic Bay naval base.

President Duterte’s February 2020 threat to abrogate the U.S.-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) was not made in a vacuum. The presence of American troops in the Philippines has long been an issue in Philippine politics. Always just beneath the surface of U.S.-Philippines relations, the matter was hotly debated in the Philippines after September 11, 2001, when the long-rebellious island of Mindanao became the epicenter of a second front in the American “war on terrorism.” The problem resurfaced in 2017 when the Americans returned to help defeat rebels there.

Divergent perspectives

The status of U.S. forces in the Philippines has been central to the often-stalled implementation of the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) to allow the U.S. military to deploy to and preposition equipment at Philippine bases the U.S. would refurbish and construct. The EDCA executive agreement required a decision by the Philippines Supreme Court to allow it to move forward without debate in the Philippine Senate, where it was certain to face opposition. The U.S. and much of Manila’s foreign policy elites may see EDCA as a “slam dunk” in their common front against China’s rise. In Manila, it remains anything but.

President Duterte’s rhetoric of an “independent foreign policy” taps into these potent strains in Philippine politics. By “independent” he means a foreign policy not dependent on the U.S. In the process of pursuing this policy, the president could lead the Philippines into an overly dependent relationship with China, but that possibility is less politically charged. Often portrayed as hypocrisy by his detractors in Washington, Mr. Duterte’s position is perceived as naturally fitting in the Philippines.

The Philippines’ struggle for autonomy is also reflected in its diplomatic tradition. Carlos Romulo (1898-1985), its most celebrated statesman, who served eight Philippine presidents as foreign minister during the Cold War, was famously pro-American. Even he, however, limited as Manila was by the contest between the West and global communism, sought a degree of independence in relations with Washington.

Romulo was an author of the United Nations Charter and a lifelong advocate for the organization, not least because of the weight it affords smaller countries. Still today, the Philippines treasures its UN membership – where it voted against the U.S. most of the time both before and during President Duterte’s administration.

Analysts who today imagine unifying Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, around a neo-containment strategy of China should also consider what Mr. Romulo said of the founding of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN): “We did not phase out SEATO [the American-led Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, 1955-1977] to set up another one.” The Philippines’ membership in ASEAN remains a pillar of its foreign policy.

The way Manila sees its role in the world is not simply a reflection of how outside powers perceive it. Foreign forces may buffet it, but the Philippines’ history and traditions condition the way it reacts. In light of these considerations, the question is how events will play out in the island nation through Mr. Duterte’s office term in 2022 and into his successor’s term.

The South China Sea claims

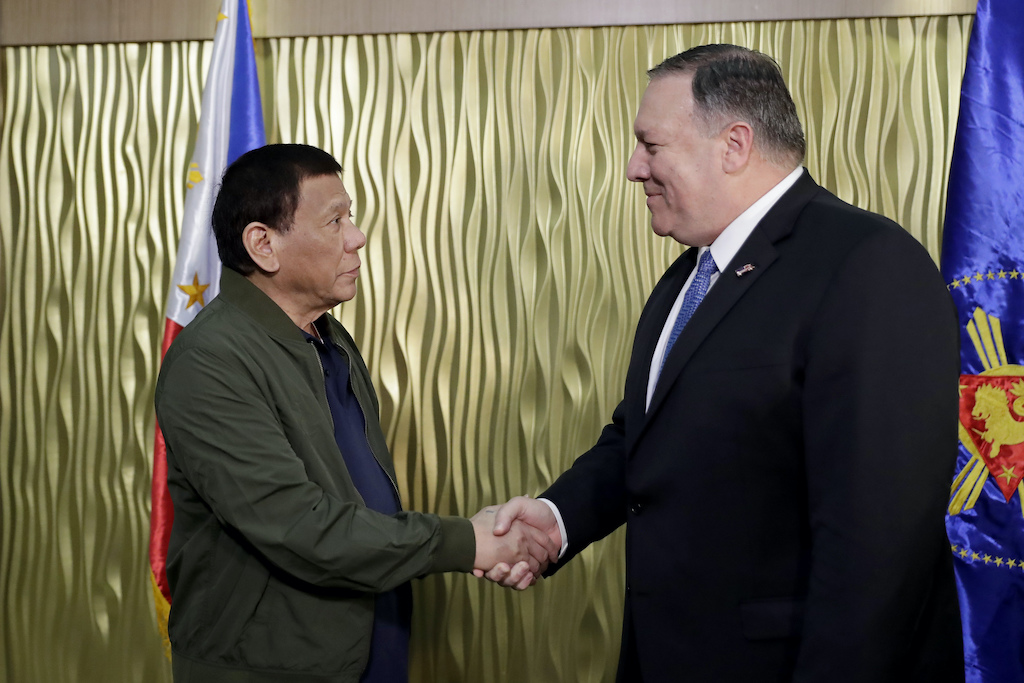

U.S. and Philippine interests in the South China Sea are not identical. The Philippines has territorial claims there on which the U.S. is neutral. However, the U.S. is treaty-bound to respond to any attack on the Philippines or its armed forces or “public vessels” operating in the South China Sea. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reaffirmed this commitment in 2019.

Despite consistent American assurances, Manila is fully aware that any U.S. response to a threat would be situational. From the Philippines’ perspective, this implies uncertainty over Washington’s potential reaction to aggression from China. Even America’s staunchest friends in Manila have sought clarification on U.S. commitments. Meanwhile, the ambiguity fuels President Duterte’s charges of American unreliability and his related accommodation of China.

Washington will also insist on maintaining autonomy in its decision making.

The U.S. side of this equation is not likely to change. The Philippines’ maritime territory claim in the South China Sea has its faults and overlaps not only with China’s, but also Taiwan’s and Vietnam’s. It is difficult to imagine the U.S. supporting Philippine claims over all comers. Washington will also insist on maintaining autonomy in its decision-making. The texts of all its Pacific security treaties allow flexibility in response to threats. Nevertheless, the U.S. will continue to express support for the Philippines’ security in the South China Sea along the lines shown by Secretary Pompeo. It will seek to build the Philippines’ capacity to resist Chinese encroachments on the Philippines’ claimed territory and increase the U.S. military presence in the region.

On the Filipino side, skepticism about American assurances is likely to continue at least through Mr. Duterte’s term in office. The president’s accommodation of Beijing has led to his neglect of a landmark case won for its maritime claims at the international Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2016. A new Philippine president may be willing to pick the matter up again. This would certainly come at a cost to Philippines-China relations.

Under this scenario, even the most pro-American president of the Philippines would need to have high confidence in the U.S. to risk such a step. This would entail, if not a change of the U.S. treaty obligations and its calibrated support of the Philippines’ territorial claims, at least a steady assertion of U.S. military presence.

Even if these conditions were met, following up on the 2016 verdict may be an iffy proposition for the Philippines – with much riding on who is U.S. president and on China’s behavior.

Human rights roadblock

A human rights issue precipitated the most recent Manila-Washington crisis over the military forces’ agreement. The State Department revoked, under pressure from the U.S. Senate, the entry visa of former chief of the Philippines National Police and commander of President Duterte’s merciless war on drugs, Senator Ronald Dela Rosa. Furious, the Philippines leader responded by banning all cabinet officials’ travel to the U.S. and triggering a process for ending the VFA.

No matter who the next president of the Philippines is, there will continue to be differences on human rights issues.

Human rights issues will continue to be an obstacle to better mutual relations through the end of Mr. Duterte’s term. No new significant initiatives – such as negotiating a bilateral FTA, for which the Philippines would be a natural partner in the current strategic environment – can be expected. Even if the next U.S. administration were so inclined, opposition in Congress would be too strong.

Mr. Duterte’s departure from office could ease human rights conflicts with the U.S., assuming the new administration ends the excesses of the country’s war on drugs. No matter who the next president of the Philippines is, there will continue to be differences on human rights issues. The focus of the U.S. Congress on the case makes continuing tension virtually certain.

New initiatives with the Philippines will be possible but require both a more cooperative Philippine leader and a push by the American president. A President Biden will be less likely to push than a President Trump, but if he does, he will find a more pliable Congress.

The Philippines and China

Philippine history points to a default position on China that is not confrontational or in automatic alignment with Washington. President Duterte’s predecessors, including Presidents Fidel Ramos (1992-1998), Gloria Arroyo (2001-2010) and Benigno Aquino (2010-2016), all pursued constructive relations with Beijing – if in the case of the latter, unsuccessfully. Whereas a new, more U.S.-friendly president will enable more consistent cooperation with Washington, it is not likely to change real Philippine interest in relations with China.

For Manila, as salient as the South China Sea issue is, it is not the sum total of its relationship with Beijing. Trade and investment ties continue to grow, despite the strength of markets for Philippine goods in the U.S. and Japan, and disappointment around China’s failure to meet investment commitments.

Grand-scale geopolitical concern over China’s rise will not be a driver of the Philippine foreign policy.

Economic activity will continue to facilitate closer Philippines-China relations. If the Chinese break the current trend and find ways to truly appease the Philippines over differences in the South China Sea, these economic ties will assume greater importance. As long as there is no new, major Manila-Beijing dispute, grand-scale geopolitical concern over China’s rise will be an academic issue in the Philippines, not a matter that would drive the Philippine foreign policy.

To the extent that Philippine leaders become concerned about excessive Chinese influence on their economy, they will look to Japan as much as to the U.S. to dilute it.

Scenarios

There are sources of stability in the Philippine foreign policy that go beyond the theatrics of its current president. Some of these are interests that do not change, like the economic benefits of its relations with China or, conversely, the obstacles to Philippines-China relations that stem from conflicting territorial designs. Similarly, the U.S. exerts a strong pull on the Philippines for economic reasons and the virtually indispensable role the Americans play in the Philippines’ security.

There are, however, even deeper sources of the country’s behavior on the international scene. In evaluating how Manila looks to secure its proximate interests and how it is likely to respond to events affecting them, it is necessary to look at how it sees its history and traditions.